Sun, Feb 22, 2026

Volume 16, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PTJ 2026, 16(1): 25-38 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Salsali M, Piri H, Setarehdan S K, Soltanlou M, Ghasemian M, Sheikhhoseini R, et al . Gender Differences in Prefrontal Brain Activation Across Sitting Postures: A Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy Study. PTJ 2026; 16 (1) :25-38

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-776-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-776-en.html

Mohammad Salsali1

, Hashem Piri2

, Hashem Piri2

, Seyed Kamaledin Setarehdan3

, Seyed Kamaledin Setarehdan3

, Mojtaba Soltanlou4

, Mojtaba Soltanlou4

, Mohammadreza Ghasemian5

, Mohammadreza Ghasemian5

, Rahman Sheikhhoseini *2

, Rahman Sheikhhoseini *2

, Sajjad Abdollahi6

, Sajjad Abdollahi6

, Fateme Soltani1

, Fateme Soltani1

, Hashem Piri2

, Hashem Piri2

, Seyed Kamaledin Setarehdan3

, Seyed Kamaledin Setarehdan3

, Mojtaba Soltanlou4

, Mojtaba Soltanlou4

, Mohammadreza Ghasemian5

, Mohammadreza Ghasemian5

, Rahman Sheikhhoseini *2

, Rahman Sheikhhoseini *2

, Sajjad Abdollahi6

, Sajjad Abdollahi6

, Fateme Soltani1

, Fateme Soltani1

1- Department of Corrective Exercise & Sport Injury, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Corrective Exercise & Sport Injury, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Engineering, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology and Human Development, Institute of Education (IOE), University College London (UCL), London, United Kingdom. & Department of Childhood Education, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

5- Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

6- Department of Sport Biomechanics, Faculty of Sports Sciences, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran.

2- Department of Corrective Exercise & Sport Injury, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Engineering, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychology and Human Development, Institute of Education (IOE), University College London (UCL), London, United Kingdom. & Department of Childhood Education, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

5- Department of Motor Behavior, Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran.

6- Department of Sport Biomechanics, Faculty of Sports Sciences, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran.

Keywords: Sitting posture, Inhibition, Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), Processing speed, Processing accuracy

Full-Text [PDF 1757 kb]

(734 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1536 Views)

Full-Text: (140 Views)

Introduction

Whether for work or recreation, a significant portion of people spend a lot of time sitting. Increased sitting time may be harmful to people’s health, particularly psychological and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression [1, 2]. Risk factors for incorrect posture include a sedentary lifestyle, low levels of physical activity, and improper sitting posture [3]. This problem has been worsened by the current technology era, which has increased people’s poor posture, especially among students expected to conform to greater academic requirements [4, 5]. Long-term computer and smartphone use combined with a sedentary lifestyle might weaken the surrounding soft tissues by causing stiffness in the shoulders and neck muscles [6, 7]. This can often result in forward head posture (FHP), which is defined by chronic muscle contractions that impair the craniocervical junction and increased lordosis at the skull-neck intersection [7, 8]. Interestingly, people who spend much time in front of computers are more likely to acquire FHP [8]. Furthermore, studies indicate that these lifestyle and postural factors may impact psychological cognitive functions [9]. Therefore, it makes sense to investigate the possible connections between posture and cognitive function in more depth. This is because postural abnormalities that result in muscle imbalances and tension can also induce cognitive impairment in professionals, students, and those who spend a lot of time sitting [5]. Research indicates a relationship between cognitive functions and bodily cues, showing that body position significantly impacts cognitive function [10]. According to the literature, sitting upright improves cognitive processing, while slumped postures are associated with reduced cognitive function [10, 11]. This emphasizes the importance of investigating how body position affects cognitive function to enhance our understanding of the complex interaction between posture and cognition. Although some studies have reported no change in specific cognitive characteristics across different sitting positions, the accuracy of these findings has not yet been established beyond a reasonable doubt [10]. Additionally, most studies included in these findings utilized intentionally adjusted postures [10, 12]. As a result, it is reasonable to adjust the height of the desks and chairs to prevent participants from being aware of the study’s manipulation and to encourage them to adopt a particular posture.

Inhibition control indicates the ability to control inappropriate behavior or override the processing of distracting or irrelevant information [13]. It is strongly connected to young people’s mental health [14] and positive habits [15]; thus, associations with postural habits in individuals may be possible. Effective inhibition control is related to forming and keeping good habits and fostering behaviors that support long-term health and productivity [14, 16]. Given its importance, there is a growing interest in understanding how different factors, including postural habits, can influence inhibition control [17, 18]. Owing to its significance, there is a rising curiosity about how various elements, such as posture, can affect inhibitory control. Research suggests that our physical posture can impact our mental health and cognitive function. This indicates that how we sit, stand, or walk may influence our ability to manage distractions and maintain focus [19]. Exploring the connections between postural habits and cognitive functions, like inhibition control could provide useful insights into suggestions for enhancing mental health and maximizing cognitive performance in everyday life [20].

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) assessments using optical absorption reveal hemodynamic changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) that are important for understanding cognitive functions, including postural control [21]. fNIRS records changes in regional cerebral blood flow, showing higher oxygenation in activated brain regions, similar to how magnetic resonance imaging identifies brain activity. These activations can provide insight into the brain mechanisms controlling postural stability and cognitive performance since they are closely associated with cognitive tasks [22]. Specifically, the PFC is critical for executive functions, including motor planning, attention, and decision-making—all of which are necessary for maintaining balance and proper posture [13]. Research has demonstrated that deficits in postural control and cognitive function are linked to disturbances in prefrontal activation [23]. Understanding the connection between posture and prefrontal activation/cognitive functions is essential for clarifying how the brain integrates sensory information to coordinate motor responses and maintain stability in various environmental settings [14]. A growing body of research indicates that postural behaviors may impact cognitive function [10], and some studies have found a link between postural modifications and prefrontal activation [23]. To definitively prove this association, more research is necessary. Using fNIRS, we can evaluate the relationship between changes in various sitting postures during cognitive processing and the temporal dynamics of prefrontal activation. In addition to advancing our knowledge of the neurological underpinnings of postural control, this research will shed light on the potential effects of various sitting postures on cognitive performance, which will have ramifications for ergonomics and posture-correction techniques [10, 24].

Furthermore, previous studies suggest that gender differences significantly affect prefrontal brain activation and cognitive tasks [25]. Studies reveal that differences in brain structure and function across genders may affect how males and females react to certain postural demands and cognitive tasks [26, 27]. For example, prior research has demonstrated that cerebral blood flow patterns and cognitive strategies may differ in females and males [25, 27]. Gender analysis allows us to investigate whether male and female prefrontal activation patterns and postural control methods differ when they complete cognitive tasks in various sitting postures. This may enable us to provide more effective cognitive enhancement and posture correction procedures tailored to different genders.

Despite numerous studies on the effects of sitting postures on cognitive functions [24], limited research has examined the effects of these postures on brain activity, especially in the PFC [10]. In addition, most of the existing studies have not paid sufficient attention to gender differences in this field. This is while gender differences in brain activation patterns and postural control strategies can affect cognitive function differently. Therefore, examining the effects of sitting postures on PFC activity by considering gender differences can lead to a better understanding of the relationship between body posture, brain function, and cognition. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the effects of sitting posture on prefrontal brain activation while emphasizing gender differences in these responses. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that (A) gender would significantly influence prefrontal activation and inhibition control patterns across different postures, and (B) prefrontal activation and inhibition control would be affected during different sitting postures.

Materials and Methods

Participants

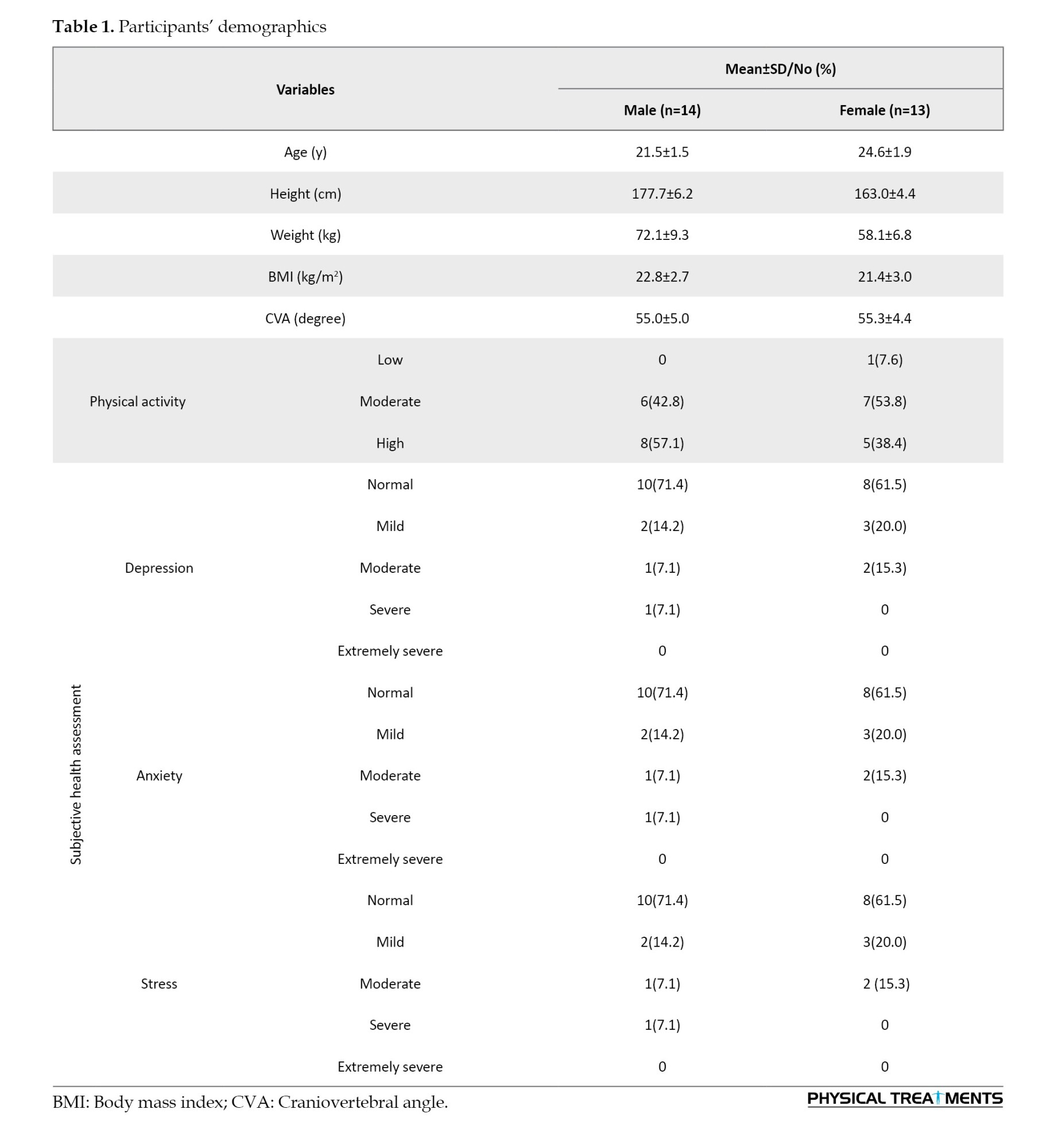

Twenty-seven students from Allameh Tabataba'i University in Tehran, Iran (14 males, age=21.5±1.5 years, 13 females, age=24.6±1.9 years) participated in this study. We determined that, with an effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.5, a power of 0.8, and an alpha level of 0.05, the necessary sample size was 27. This sample size was determined using G*Power software, version 3.1 based on an effect size (Cohen's d) derived from a previous related study examining posture effects on cognitive functions [28]. In other words, prior research reported moderate effect sizes, justifying the selection of 0.5 to ensure adequate statistical power. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The following criteria were listed as exclusions: 1) previous or current medical or psychological disorders, 2) having FHP, 3) being left-handed, as defined by the short form of the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [29]. Left-handed individuals were excluded since students would use their right hands to answer the stop-signal task. All study participants provided written informed consent after receiving study information.

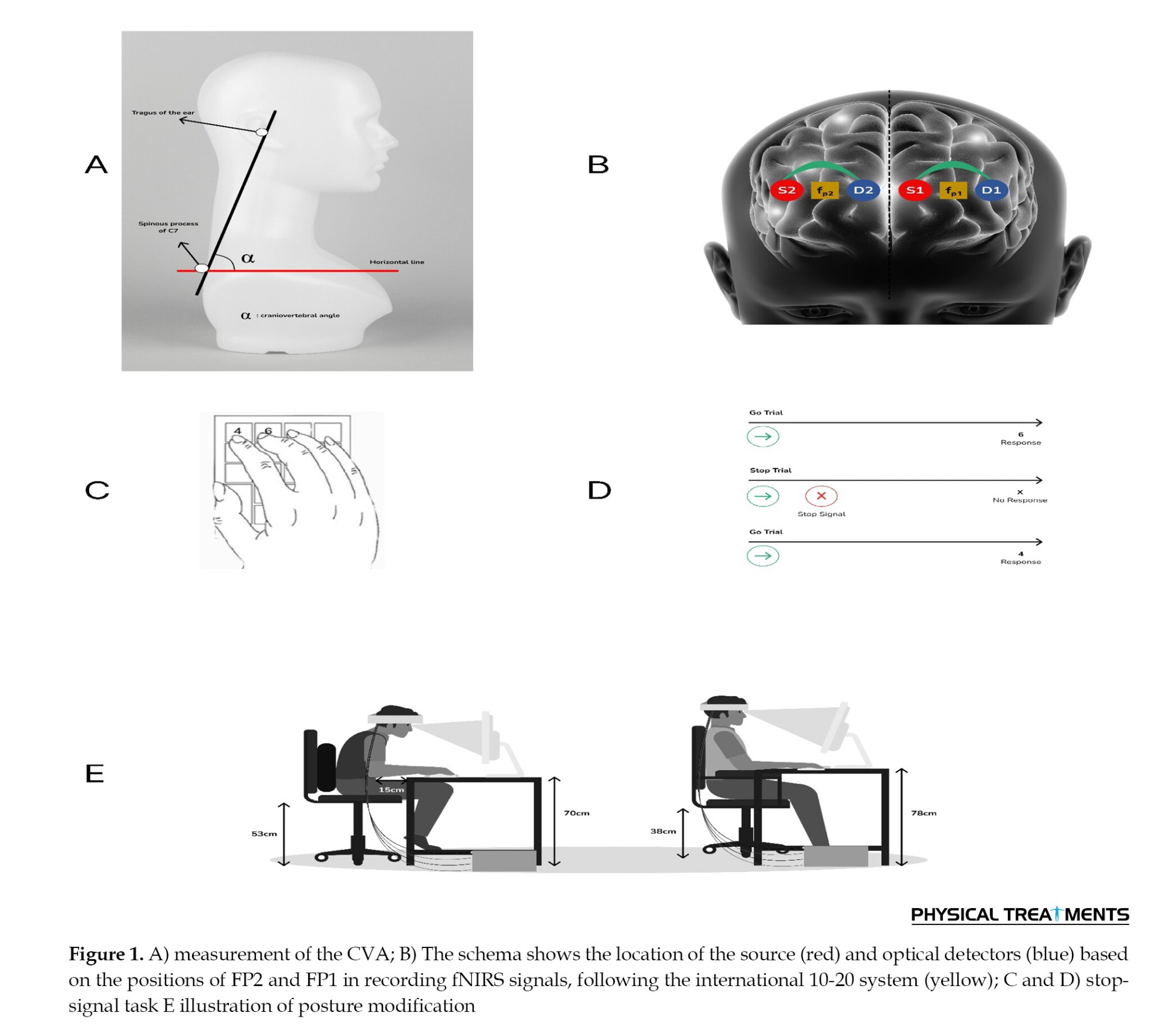

Body posture manipulation

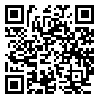

The purpose of the posture adjustment was to prevent the participants from paying attention to their own posture [10]. As a result, before the test, we altered the participants’ chairs and height-adjustable computer monitors, manipulating their posture: The desk and computer monitor were situated at a reasonably high height for the group that was seated upright, and the chairs were placed at a relatively low height (height of desk+computer: 78 cm; height of chair: 38 cm). Additionally, it was determined that there should be no space between the subjects’ trunks and the table. The manipulation was reversed for the group instructed to sit with FHP (height of desk+computer monitor: 70 cm; height of chair: 53 cm; distance of trunk from the table: 15 cm (Figure 1). The findings demonstrated that when the distance between the trunk and desk was 15 cm, the shift in FHP was much greater during computer use [30]. However, using support in the thoracic region also causes the thoracic spine and trunk to shift forward, leading to thoracic kyphosis. In this circumstance, the head may lean forward and downward [31]. Therefore, to assist subjects with FHP, we provided support in the thoracic spine region. We modified these adjustments based on the height of Iranian students. According to data from 911 Iranian universities [32], male and female students in Iran aged 18 to 25 are, on average, 1.74 meters and 1.59 meters tall, respectively [32].

Measures

Questionnaire

The international physical activity questionnaire-short form (IPAQ-SF) was utilized to evaluate the physical activity levels of the included participants. This assessment evaluated the physical activity undertaken in the week prior. This questionnaire’s validity (0.85) and reliability (0.70) in Persian were both confirmed [33]. To translate the IPAQ data to MET-min/week for each type of activity, the number of minutes spent on each activity category was multiplied by the specific metabolic equivalent (MET) score for that activity. The energy cost of each activity type is considered when calculating the MET score. One MET is roughly equivalent to 3.5 mL O2/kg/min in adults and measures energy expenditure while at rest. According to the IPAQ’s scoring system, physical activity levels were ultimately divided into three levels: light, moderate, and vigorous [34, 35].

Moreover, we used the depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) to assess the mental health of participants. This questionnaire has high reliability (Cronbach’s α>0.90) and demonstrated validity across diverse populations [36]. According to reports, its Cronbach’s α scores for depression, anxiety, and stress in the Iranian population were 0.77, 0.79, and 0.78, respectively [37]. Each category of mental health, comprising depression, anxiety, and stress, is covered by 7 items in this questionnaire. The ratings for the responses range from zero (“did not apply to me at all”) to three (“applied to me very much or most of the time”) on a Likert scale. The total score for each scale was determined by summing the scores for the relevant items and multiplying by two, resulting in a possible range of 0 to 42. Participants were categorized into five levels of depression, anxiety, and stress: normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. To assess the severity of each sub-scale, we employed the cut-off scores suggested by Lovibond and Lovibond [36]. Consequently, scores ≥21, 15, and 26 (respectively) for depression, anxiety, and stress were deemed serious. A higher score on each scale indicated a more severe mental condition [36, 38].

Test paradigm: Response inhibition test

In our research, we evaluated inhibitory control using the stop signal paradigm (Schuhfried GmbH, Austria) (form S1; [39]). A set of arrows pointing either left or right is displayed on a screen in this task [40]. In order to respond, participants must press the "5" key to indicate a left arrow or the "6" key to indicate a right arrow as rapidly as possible (Figure 1). Each arrow is shown for one second, followed by a one-second blank screen. The test consists of a total of 200 trials, divided into two parts of 100 trials each.

Stop signal delay (SSD) and stop signal reaction time (SSRT) are two of the four main factors measured by the stop signal paradigm. The SSRT measures how long it takes to suppress a response after it has been presented. The interval between the display of the go stimulus and the stop signal is referred to as the SSD [41]. Furthermore, records were kept of commission errors, which are incorrect responses to go trials, and omission errors, which are missed responses to go trials.

fNIRS measurement

In this work, we employed the Oxymap124 fNIRS system of the University of Tehran. The Oxymap124, which is a continuous wave (CW) fNIRS device, operates at two wavelengths of 730 and 850 nm with a sampling rate of 10 Hz. Two optodes were applied to the forehead using double-sided medical adhesive, with the midpoint of each probe centered on the Fp1/Fp2 locations according to the International 10-20 system (Figure 1). An elastic cap was then placed over the optodes on the head to shield them from ambient light. The PFC was chosen as the location for signal recording because it is connected to higher cognitive and attention activities [42]. The source-detector distance of each Optod was set to 25 mm. Both fNIRS channels were categorized as belonging to Brodmann area 10 (BA 10), which contributes to attention, inhibitory control [43], and prefrontal oxygenation [44]. Numerous NIRS investigations document changes in brain activity (BA) 10's hemodynamics, with the majority conducted on healthy individuals. In the data provided, the distribution of medial and lateral alterations appears to be equal. While medial BA 10 was reported to exhibit oxygenated deactivations after pain (5/5 studies), lateral BA 10 is more frequently linked to oxygenation activations (4/5 studies) [44].

In accordance with probabilistic anatomical craniocerebral correlation [45], probes were projected to belong to the left and right medial PFC (MPFC). To prevent motion artifacts, participants were asked to minimize head movements during signal recording [42, 46].

Procedure

The craniovertebral angle (CVA), determined by the position of the head when viewed laterally at the seventh cervical (C7) vertebra, was measured to determine whether the patients had FHP. This angle is obtained by drawing a line through the C7 vertebra’s spinous process on the horizontal plane and connecting it to the tragus of the ear with another line (Figure 1). The angle decreases as the head position is perceived to be more forward [47]. The subjects focused on a fixed point that corresponded to their eye height while maintaining an upright position and relaxing both arms alongside their trunks. The locations of the tragus of the ear and the spinous process of the C7 vertebra were noted to accurately assess the position when taking a photograph. A digital camera mounted on a tripod was then placed 80 cm from the participants while they stood next to the wall in a specified area. Each participant’s C7 vertebra served as the reference point for the height adjustment of the camera. Participants were instructed to stand naturally and securely with their arms above their heads three times while concentrating on an imagined spot on the wall. A tester took three pictures from the lateral side after a 5-second interval. The CVA was ultimately determined by transferring the selected picture to a computer and utilizing ImageJ software (Rasband, USA) [48]. A CVA of less than 48–50 degrees is considered indicative of FHP, with a smaller CVA suggesting a greater degree of FHP. In this study, the CVA cut-off was set at 48; patients with a CVA of 48 or less were classified as having FHP, while those with a CVA of 48 or more were classified as healthy [31]. Thus, the CVA criterion for FHP in this study was established at ≥48°.

Previous research on cognitive task performance has demonstrated that effects may not be present when respondents are informed about the context of the investigation [10]. Therefore, our participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study at the end of the experiment. Testing was conducted at the same time of day for all participants. Each participant completed the task twice: once in an upright posture and once in FHP. To control for order effects, participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Half of the participants began the task in an upright posture and then switched to FHP, while the other half started in FHP and then switched to the upright posture. A ten-minute rest period was provided between the two postures to prevent participants’ mental states from adapting to the cognitive task.

First, participants were required to complete the IPAQ-SF and DASS in their considered posture for the task. This means that before beginning the cognitive task and fNIRS measurement, participants had been in the altered posture for approximately 5 minutes. Following the instructions, participants completed the stop-signal task while fNIRS measurements were taken in a quiet and dimly lit room.

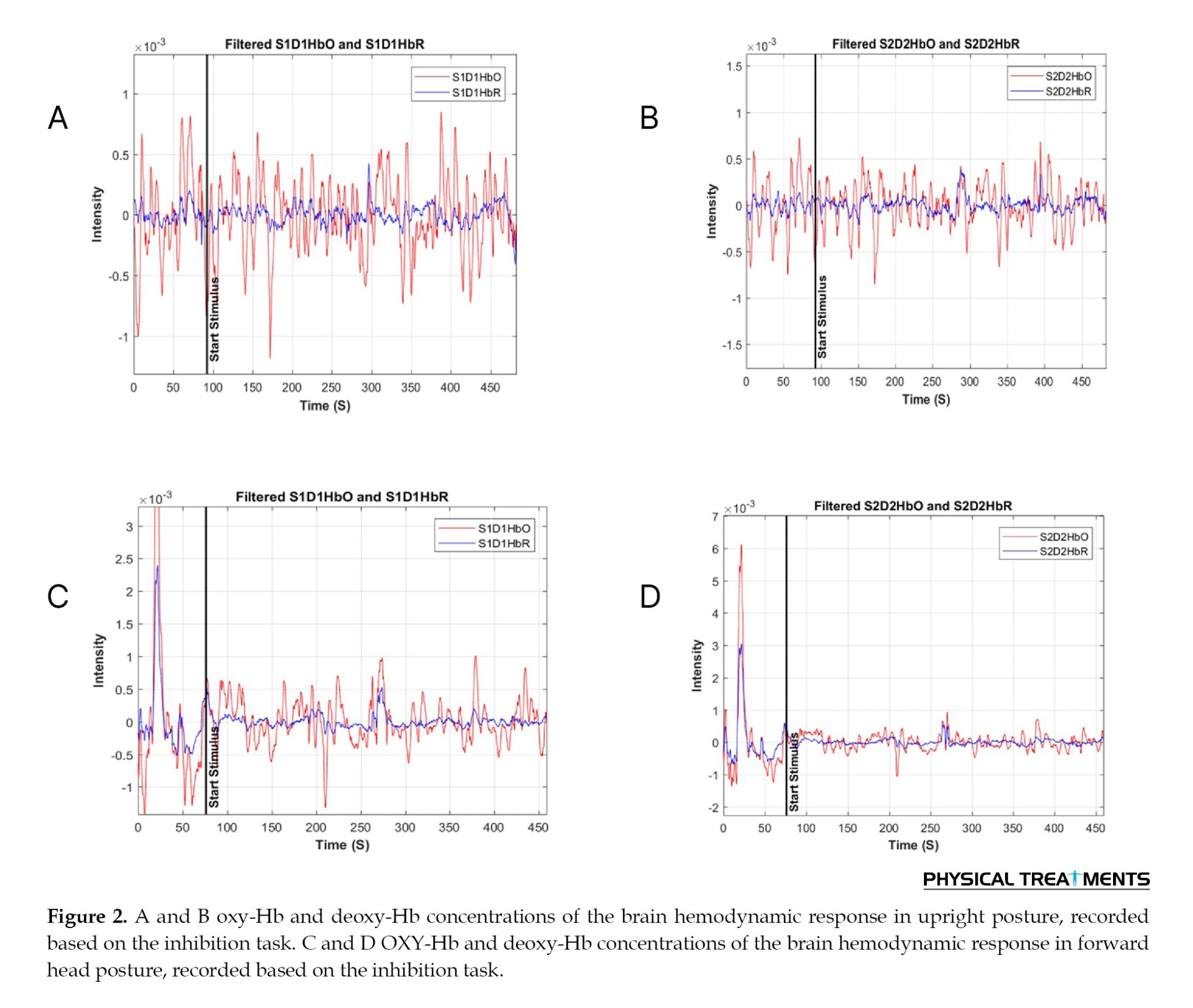

fNIRS data pre-processing

The fNIRS signals captured in the present study were pre-processed using the HomER3 package [49], which was implemented in MATLAB software, version R2020a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). We applied a 4th-order Butterworth band-pass filter with a pass range of 0.01-0.9 Hz to eliminate physiological artifacts while preserving functional data [50, 51]. Motion artifacts were corrected using wavelet-based techniques available in HomER3 [52, 53].

To eliminate slow signal drifts, baseline drifts were adjusted using a high-pass filter [52]. For additional analysis, the raw light intensity data were transformed to optical density [49]. Using the modified Beer-Lambert law, the fNIRS device automatically converted optical density to changes in concentrations of OXY-Hb and Deoxy-Hb.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 24.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA). The homogeneity of variances and normality of the distribution of the parameters were tested using Levene’s and Shapiro-Wilk’s tests, respectively. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed in order to assess the stop signal task and hemodynamic changes. Our experimental design determined posture as the within-subject factor, representing the time variable with two levels: upright and FHP. Additionally, gender was the between-subject factor, with participants grouped into male and female categories. Partial eta squared was used as an effect size. Statistical significance was set at the level of P<0.05.

Results

Participants’ demographics

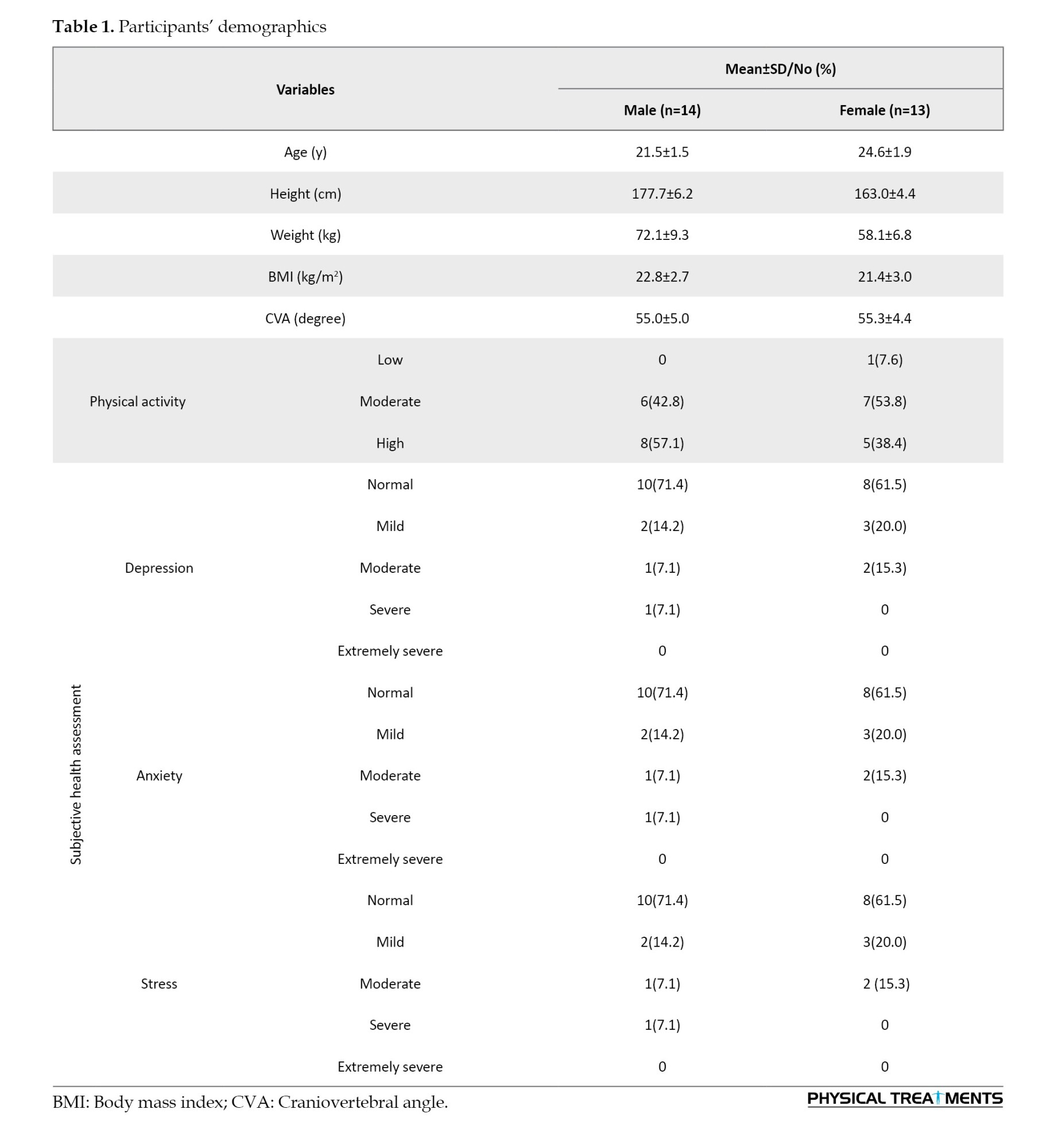

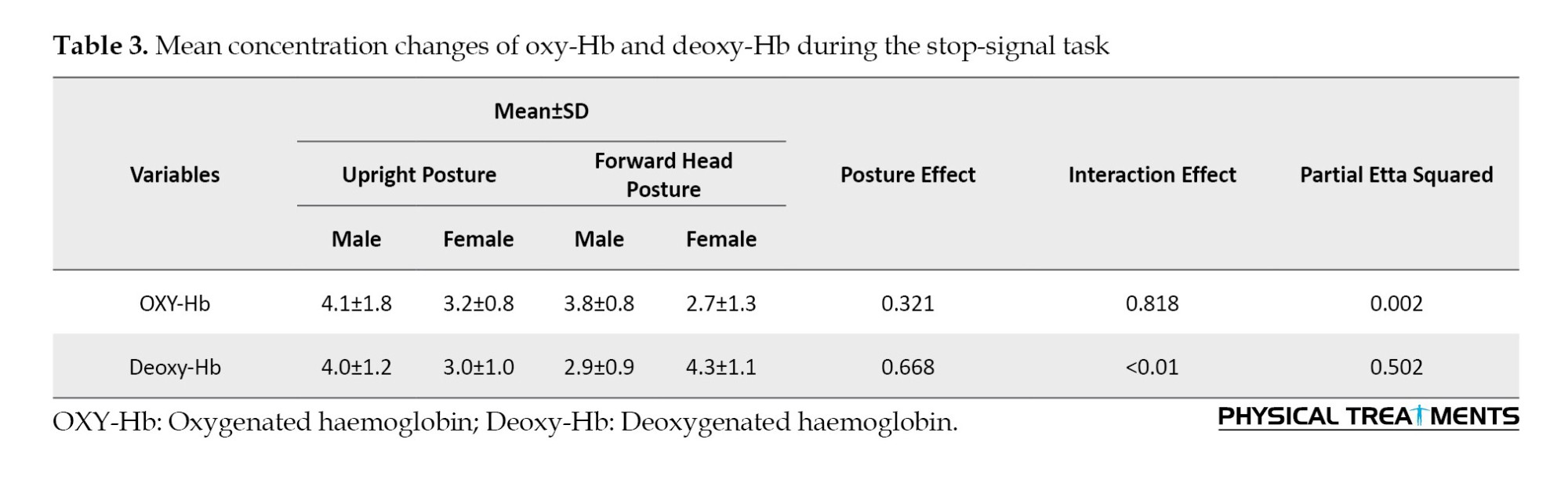

The demographic data presented in Table 1 show key differences between genders in physical characteristics and health assessments. Significant differences in physical activity levels were seen between genders. Compared to females (38.4%), a considerable percentage of males (57.1%) reported high physical activity levels. On the other hand, 71.4% of males and 61.5% of females reported normal depression and anxiety levels, while similar proportions reported typical stress levels.

This contextual data assures that the participants’ backgrounds will be appropriately considered when interpreting the results. Furthermore, the previously mentioned demographic findings underscore significant differences and similarities between male and female participants, providing a basis for comprehending plausible impacts on research outcomes.

Cognitive performance

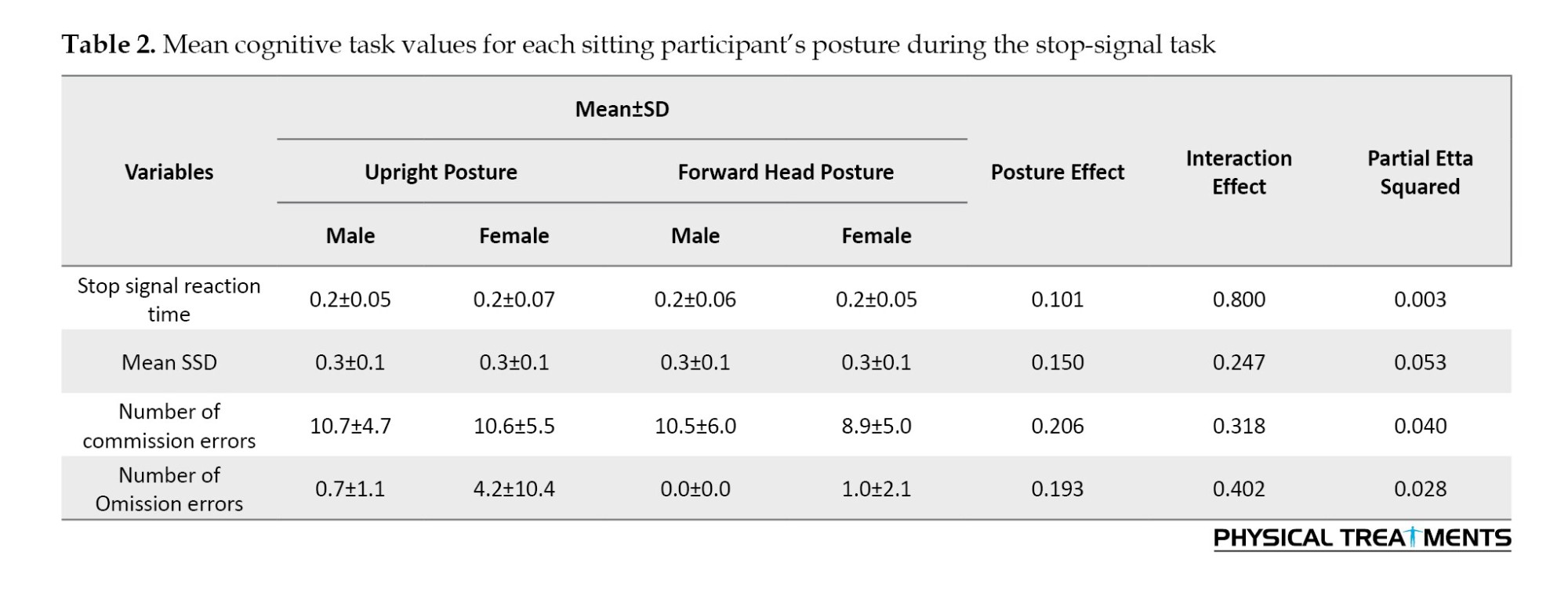

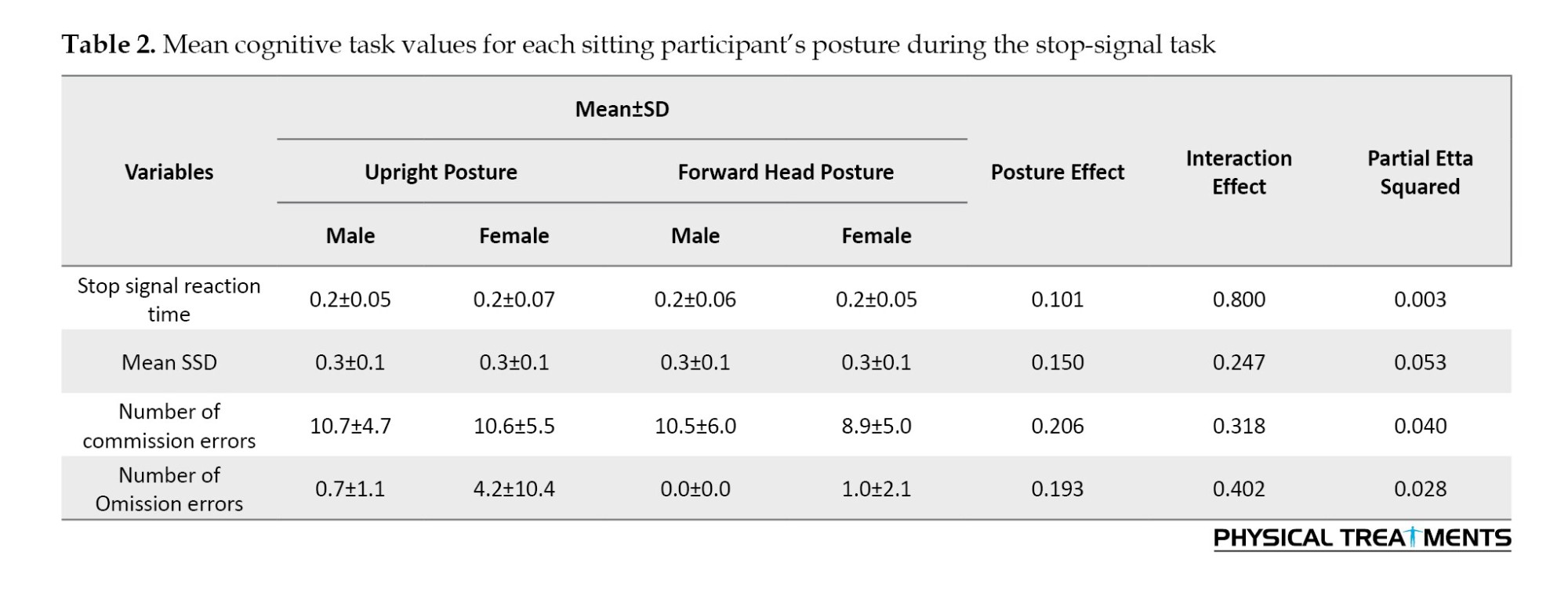

Stop signal reaction time

Both male and female participants were tested for the SSRT in their FHP and upright positions. There were no significant gender-posture interactions (P=0.800) or differences in SSRT across the two postures (P=0.101, partial η2=0.003). This suggests that the speed of the inhibition process was not substantially affected by either gender or posture (Table 2).

SSD

In addition, the mean SSD for both genders and postures was assessed. The findings revealed no gender or statistically significant differences in SSD between the forward and upright head postures (P=0.150, partial η2=0.053). This implies that SSD did not vary based on the individual’s gender or posture (Table 2).

Error Analysis

We examined commission and omission errors to evaluate the participants’ accuracy. In the FHP (Mean±SD, 9.74±5.57) compared to the upright posture (Mean±SD, 10.7±5.04), there were fewer commission errors; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.206, η2=0.040). The number of commission errors in each posture was not substantially influenced by gender (P=0.318).

Gender did not have a significant effect on omission errors (P=0.402), and there were no significant differences between postures (P=0.193, η2=0.028). These results imply that neither gender nor posture had discernible effects on the error rates (Table 2).

These results demonstrate that posture and gender did not significantly impact cognitive task performance regarding SSRT, SSD, and error rates.

Hemodynamic changes

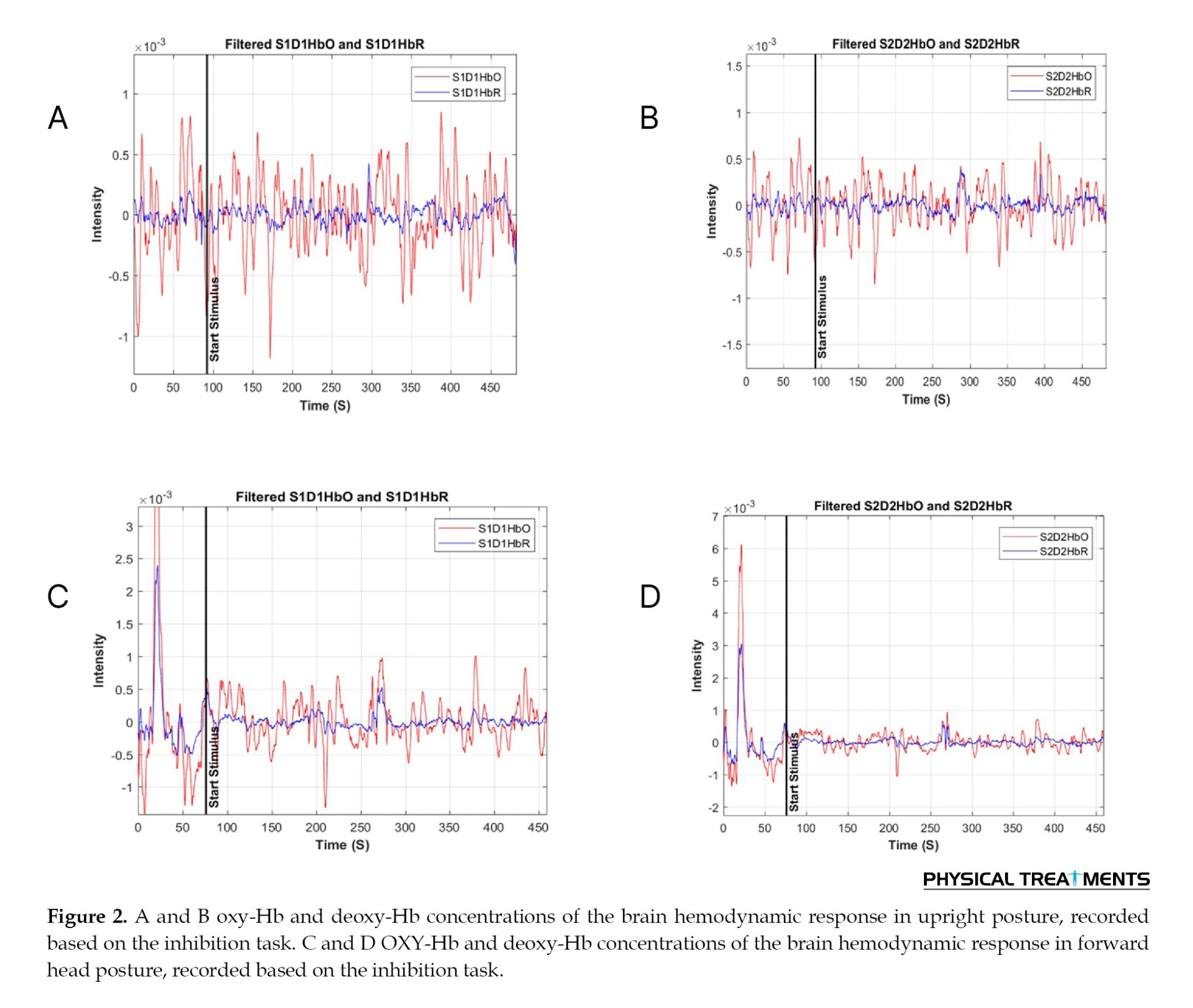

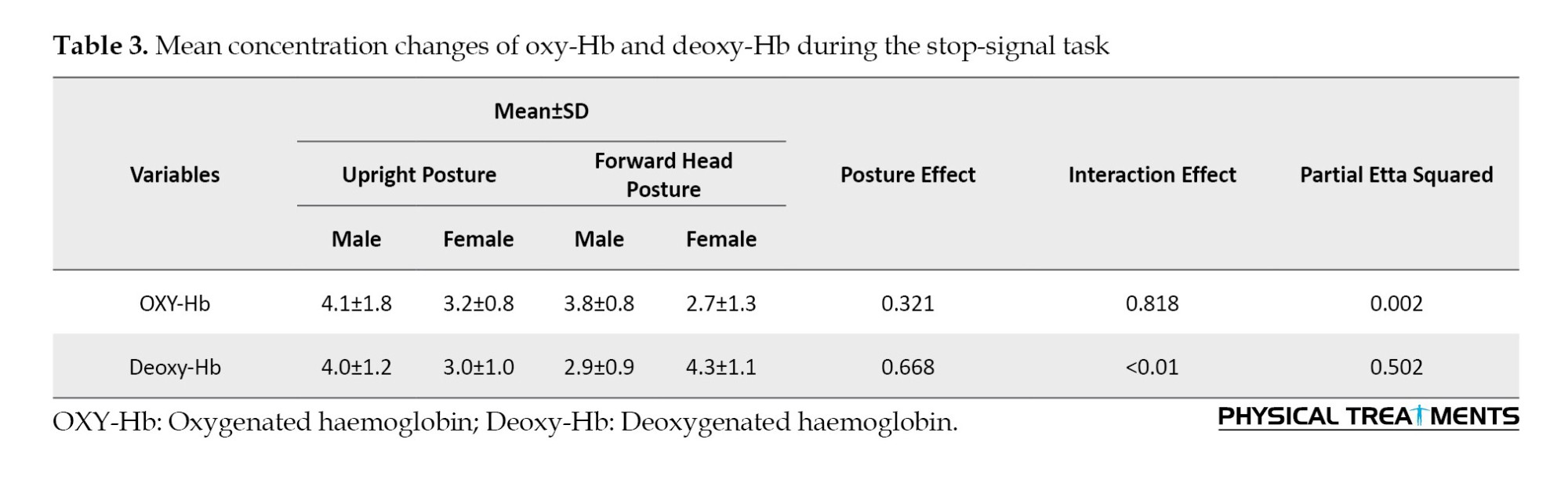

To analyze hemodynamic changes, we measured the levels of oxygenated hemoglobin (OXY-Hb) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (Deoxy-Hb) in both upright and FHPs for male and female subjects. Different sitting postures and genders yielded different OXY-Hb and Deoxy-Hb values.

OXY-Hb

Gender and posture differences were observed in the mean OXY-Hb values. The mean OXY-Hb level in the upright posture was 4.1±1.8 for male participants and 3.2±0.8 for female participants (Figure 2). The OXY-Hb levels in the FHP were 2.7±1.3 in males and 3.8±0.8 in females. It appears that posture did not significantly affect OXY-Hb levels across genders, as revealed by the ANOVA results, which showed no significant interaction effect for OXY-Hb values (P=0.321, partial η2=0.002).

Deoxy-Hb

Deoxy-Hb levels were found to follow different patterns depending on gender and sitting posture. In the upright posture, the mean deoxy-Hb level for male participants was 4.0±1.2, whereas that for female participants was somewhat lower at 3.0±1.0. In contrast, females exhibited a higher deoxy-Hb level of 4.3±1.1 in the FHP compared to males, who had a Deoxy-Hb level of 2.9±0.9. When considering the role of gender, the main effect of posture on Deoxy-Hb values was significant (P<0.01, partial η2=0.502), indicating that women performed the task with higher deoxy-Hb values in the FHP, which was not observed in men. Additionally, there was a significant difference in deoxy-Hb levels between males and females across different sitting postures (Table 3).

As illustrated in Figure 2, OXY-Hb values were generally higher in the upright posture (Mean±SD, 3.7±1.52) compared to the FHP (Mean±SD, 3.32±1.2). In contrast, the FHP (Mean±SD, 3.61±1.23) exhibited more intense deoxy-Hb values than the upright position (Mean±SD, 3.55±1.24). These results demonstrate how gender and posture significantly influence deoxy-Hb levels during the task.

Discussion

Our findings indicated that while short-term alterations in sitting posture do not significantly impact inhibition control or overall cognitive performance, gender differences in prefrontal oxygenation responses are evident. Specifically, females exhibited significantly higher deoxy-Hb levels in the FHP than males, suggesting distinct neural and vascular adaptations to postural changes. The main conclusions are as follows: 1) There is a statistically significant difference in Deoxy-Hb values between males and females (P<0.01); 2) Higher OXY-Hb levels were observed in the upright posture, but this was not statistically significant (P=0.321); and 3) No significant difference in task performance was found between the two sitting postures in terms of processing speed and accuracy.

Our findings indicated that posture alone may not directly impact cognitive performance, as evidenced by the lack of significant differences in processing speed and accuracy between the upright and FHPs during the stop-signal task. Regarding processing speed, previous work revealed that subjects in an upright position processed more objects in the d2-R task compared to a stoop sitting posture [10]. Nevertheless, in our experiment, no significant differences were observed in the processing speed in either the male or female participants while performing the stop-signal task. Since they applied a different cognitive task, our results are not directly comparable. We propose various theories for why other results differ from ours. One factor could be that earlier research predicted the advantageous benefits of upright posture on subject processing speed based on the number of processed items during the d2-R test [10]. Due to the differences in object processing and speed in the current inhibition task, it is possible that findings related to processing objects cannot be easily translated to speed processing as measured in the stop-signal task.

Meanwhile, we calculated the speed of processing by considering SSRT and SSD. The SSRT is the amount of time needed to stop the reaction triggered by the signal. The SSD, which is the period during which participants successfully withhold their response 50% of the time, is subtracted from the average response time to go trials to derive this inference [54]. Also, the SSD is the amount of time that passes after the arrow is displayed before the beep is heard. Using a step-by-step process, the task modifies the SSD based on performance. The SSD is reduced, making it easier on the subsequent trial when a person fails to suppress their response after failing to react to a stop signal. Conversely, the SSD is increased, raising the challenge in the following trial when the individual effectively blocks their button click in response to the stop signal [54]. By deducting SSD from the completion time, SSRT can be determined [41].

Furthermore, contrary to our predictions, there are no significant variations in the number of errors and processing accuracy between the two sitting postures in the present inhibition test. Surprisingly, in a cross-sectional study of 82 participants conducted in Germany, there was no significant difference in processing accuracy between stooped sitting posture and upright posture. Specifically, in that study, participants did not perform less accurately in an upright sitting position (Mean±SD, 10.25±9.60) than when stooped (Mean±SD, 10.14±7.42) (P=0.477). In the current study, we could not find any significant effect of posture on participants’ error analysis. Thus, it seems we should consider other possibilities for the interaction between posture and cognitive function. For instance, it is possible that posture influences attitudes and metacognitive thinking, which in turn affects cognitive performance [10]. Participants who sat in an upright posture reported feeling substantially more proud after receiving positive performance-related comments than subjects who slouched [55]. Similarly, another study indicated that participants in upright postures had more confidence in their thoughts than those in stooped positions [56].

It has been proposed that physiological changes occur as a result of an alteration in posture [10]. For instance, it has been demonstrated that an upright posture enhances electroencephalographic (EEG) arousal and focused attention, implying that postural adjustments can be beneficial in preventing fatigue in sleep-deprived individuals [57]. Furthermore, the upright participants exhibited a greater pulse pressure response throughout the stressor and recovery phases those in a slumped position [19]. During the stress task, individuals in the upright position experienced greater pulse pressure, which was sustained during the recovery time. These findings represent higher physiological arousal in the upright group compared to slumped group [10, 19]. However, our findings are not directly comparable to those of these investigations because they utilized a different task and a different postural approach. The current study showed no significant differences in prefrontal oxygenation between the two different sitting postures while performing a stop-signal task.

However, participants in upright posture exhibited higher OXY-Hb values than those in the FHP, which is in line with similar findings. This implies that sitting posture can significantly influence PFC oxygenation levels. According to studies, maintaining an upright posture can improve cerebral blood flow and oxygenation by improving cervical spine alignment, which lowers vascular resistance and encourages more effective blood circulation. Additionally, keeping the body upright may aid in respiration, potentially resulting in increased oxygen levels and, ultimately, higher OXY-Hb values. It is important to note that the impact of sitting posture on prefrontal brain oxygenation was only observed in the current study. This result is consistent with findings indicating that sustained exposure may be required to notice more severe effects and that brief posture alterations may not be adequate to produce significant changes in brain oxygenation. The minimal effects observed in our study may also be explained by individual differences in physiological adaptability and baseline cognitive function, which may reduce the impact of posture on brain oxygenation.

However, the significant difference in Deoxy-Hb values between males and females in the FHP was an especially notable observation, as females showed greater amounts. The difference in hemodynamic response between both genders highlights the need for more investigation into how sitting posture affects brain oxygenation and cognitive function differently in each gender. Females' greater Deoxy-Hb levels during the FHP may indicate different vascular or metabolic reactions to postural changes, which may be mediated by differences in hormones or anatomy [58]. This physiological reaction unique to gender may affect cognitive function, indicating the need for specialized cognitive therapies and ergonomic suggestions [59]. For example, females might benefit more from interventions that address FHP to optimize cognitive function and brain oxygenation.

Taking these gender differences into consideration, future studies should examine the long-term impact of posture on cognitive function as well as the underlying physiological mechanisms. A greater understanding of the connections between posture, cognitive function, and brain oxygenation may be achieved by extending the duration of posture exposure and utilizing a variety of cognitive tasks.

Conclusion

Within the confines of this study, significant differences were observed in deoxy-Hb levels between males and females across different sitting postures. However, overall, sitting posture did not significantly influence participants' inhibitory control abilities or prefrontal activity. The interaction between gender and sitting posture suggests potential differences in the effects on cognitive processes between males and females. It is plausible that the limited duration of sitting posture exposure may have mitigated substantial changes in cognitive performance or brain oxygenation. Future research should consider longer intervention durations and a more thorough exploration of potential confounding variables.

These findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the multifaceted elements that affect cognitive strategies and brain activity. While our observations do not yield definitive effects, they underscore the complexity of the relationship between sitting postures and inhibition control, providing valuable insights for future investigations.

Limitations and directions

The lack of significant differences in task performance and prefrontal oxygenation between the two sitting postures supports the theory that the short sitting duration in this test may not be sufficient to cause significant changes in brain oxygenation or cognitive function. The effects of sitting posture on prefrontal brain activity and inhibition control may also need longer exposure times or particular interventions to become noticeable. In addition, various factors, including individual differences in comfort and alternative postures, may have affected the outcomes.

These findings contribute to our understanding of the complex relationship between sitting postures, cognitive characteristics, and brain activity. They suggest that while sitting posture may have theoretical implications for cognitive performance and brain oxygenation, its practical significance in a short-term context can be limited.

Future studies in this area need to take several factors into account. First, extended exposure to specific sitting postures and cognitive interventions (e.g. ergonomic adjustments) may help clarify whether more significant effects develop over time. Investigating how an individual’s decisions and habits related to their sitting posture affect their cognitive abilities and mental traits may also yield insightful results..

Ultimately, this study found no significant differences in prefrontal oxygenation or cognitive function between participants in FHP and upright posture during a brief Stop-signal task. These results imply that while sitting posture remains an intriguing area of study, its effects on inhibition control and prefrontal brain activity may be minimal, necessitating further research under particular conditions and over longer periods.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SSRC.REC.1402.322).All participants signed a written informed consent form.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design and data collection: Mohammad Salsali, Hashem Piri, Kamaledin Setarehdan and Fateme Soltani; Drafting of the manuscript and made critical revision: Mohammad Salsali, Rahman Sheikhhoseini, Kamaledin Setarehdan, Mojtaba Soltanlou, Mohammadreza Ghasemian, Hashem Piri and Sajjad Abdollahi; Final Approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of Allameh Tabataba'i University for allowing the researchers to conduct this research in this laboratory.

References

Whether for work or recreation, a significant portion of people spend a lot of time sitting. Increased sitting time may be harmful to people’s health, particularly psychological and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression [1, 2]. Risk factors for incorrect posture include a sedentary lifestyle, low levels of physical activity, and improper sitting posture [3]. This problem has been worsened by the current technology era, which has increased people’s poor posture, especially among students expected to conform to greater academic requirements [4, 5]. Long-term computer and smartphone use combined with a sedentary lifestyle might weaken the surrounding soft tissues by causing stiffness in the shoulders and neck muscles [6, 7]. This can often result in forward head posture (FHP), which is defined by chronic muscle contractions that impair the craniocervical junction and increased lordosis at the skull-neck intersection [7, 8]. Interestingly, people who spend much time in front of computers are more likely to acquire FHP [8]. Furthermore, studies indicate that these lifestyle and postural factors may impact psychological cognitive functions [9]. Therefore, it makes sense to investigate the possible connections between posture and cognitive function in more depth. This is because postural abnormalities that result in muscle imbalances and tension can also induce cognitive impairment in professionals, students, and those who spend a lot of time sitting [5]. Research indicates a relationship between cognitive functions and bodily cues, showing that body position significantly impacts cognitive function [10]. According to the literature, sitting upright improves cognitive processing, while slumped postures are associated with reduced cognitive function [10, 11]. This emphasizes the importance of investigating how body position affects cognitive function to enhance our understanding of the complex interaction between posture and cognition. Although some studies have reported no change in specific cognitive characteristics across different sitting positions, the accuracy of these findings has not yet been established beyond a reasonable doubt [10]. Additionally, most studies included in these findings utilized intentionally adjusted postures [10, 12]. As a result, it is reasonable to adjust the height of the desks and chairs to prevent participants from being aware of the study’s manipulation and to encourage them to adopt a particular posture.

Inhibition control indicates the ability to control inappropriate behavior or override the processing of distracting or irrelevant information [13]. It is strongly connected to young people’s mental health [14] and positive habits [15]; thus, associations with postural habits in individuals may be possible. Effective inhibition control is related to forming and keeping good habits and fostering behaviors that support long-term health and productivity [14, 16]. Given its importance, there is a growing interest in understanding how different factors, including postural habits, can influence inhibition control [17, 18]. Owing to its significance, there is a rising curiosity about how various elements, such as posture, can affect inhibitory control. Research suggests that our physical posture can impact our mental health and cognitive function. This indicates that how we sit, stand, or walk may influence our ability to manage distractions and maintain focus [19]. Exploring the connections between postural habits and cognitive functions, like inhibition control could provide useful insights into suggestions for enhancing mental health and maximizing cognitive performance in everyday life [20].

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) assessments using optical absorption reveal hemodynamic changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) that are important for understanding cognitive functions, including postural control [21]. fNIRS records changes in regional cerebral blood flow, showing higher oxygenation in activated brain regions, similar to how magnetic resonance imaging identifies brain activity. These activations can provide insight into the brain mechanisms controlling postural stability and cognitive performance since they are closely associated with cognitive tasks [22]. Specifically, the PFC is critical for executive functions, including motor planning, attention, and decision-making—all of which are necessary for maintaining balance and proper posture [13]. Research has demonstrated that deficits in postural control and cognitive function are linked to disturbances in prefrontal activation [23]. Understanding the connection between posture and prefrontal activation/cognitive functions is essential for clarifying how the brain integrates sensory information to coordinate motor responses and maintain stability in various environmental settings [14]. A growing body of research indicates that postural behaviors may impact cognitive function [10], and some studies have found a link between postural modifications and prefrontal activation [23]. To definitively prove this association, more research is necessary. Using fNIRS, we can evaluate the relationship between changes in various sitting postures during cognitive processing and the temporal dynamics of prefrontal activation. In addition to advancing our knowledge of the neurological underpinnings of postural control, this research will shed light on the potential effects of various sitting postures on cognitive performance, which will have ramifications for ergonomics and posture-correction techniques [10, 24].

Furthermore, previous studies suggest that gender differences significantly affect prefrontal brain activation and cognitive tasks [25]. Studies reveal that differences in brain structure and function across genders may affect how males and females react to certain postural demands and cognitive tasks [26, 27]. For example, prior research has demonstrated that cerebral blood flow patterns and cognitive strategies may differ in females and males [25, 27]. Gender analysis allows us to investigate whether male and female prefrontal activation patterns and postural control methods differ when they complete cognitive tasks in various sitting postures. This may enable us to provide more effective cognitive enhancement and posture correction procedures tailored to different genders.

Despite numerous studies on the effects of sitting postures on cognitive functions [24], limited research has examined the effects of these postures on brain activity, especially in the PFC [10]. In addition, most of the existing studies have not paid sufficient attention to gender differences in this field. This is while gender differences in brain activation patterns and postural control strategies can affect cognitive function differently. Therefore, examining the effects of sitting postures on PFC activity by considering gender differences can lead to a better understanding of the relationship between body posture, brain function, and cognition. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the effects of sitting posture on prefrontal brain activation while emphasizing gender differences in these responses. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that (A) gender would significantly influence prefrontal activation and inhibition control patterns across different postures, and (B) prefrontal activation and inhibition control would be affected during different sitting postures.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-seven students from Allameh Tabataba'i University in Tehran, Iran (14 males, age=21.5±1.5 years, 13 females, age=24.6±1.9 years) participated in this study. We determined that, with an effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.5, a power of 0.8, and an alpha level of 0.05, the necessary sample size was 27. This sample size was determined using G*Power software, version 3.1 based on an effect size (Cohen's d) derived from a previous related study examining posture effects on cognitive functions [28]. In other words, prior research reported moderate effect sizes, justifying the selection of 0.5 to ensure adequate statistical power. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The following criteria were listed as exclusions: 1) previous or current medical or psychological disorders, 2) having FHP, 3) being left-handed, as defined by the short form of the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [29]. Left-handed individuals were excluded since students would use their right hands to answer the stop-signal task. All study participants provided written informed consent after receiving study information.

Body posture manipulation

The purpose of the posture adjustment was to prevent the participants from paying attention to their own posture [10]. As a result, before the test, we altered the participants’ chairs and height-adjustable computer monitors, manipulating their posture: The desk and computer monitor were situated at a reasonably high height for the group that was seated upright, and the chairs were placed at a relatively low height (height of desk+computer: 78 cm; height of chair: 38 cm). Additionally, it was determined that there should be no space between the subjects’ trunks and the table. The manipulation was reversed for the group instructed to sit with FHP (height of desk+computer monitor: 70 cm; height of chair: 53 cm; distance of trunk from the table: 15 cm (Figure 1). The findings demonstrated that when the distance between the trunk and desk was 15 cm, the shift in FHP was much greater during computer use [30]. However, using support in the thoracic region also causes the thoracic spine and trunk to shift forward, leading to thoracic kyphosis. In this circumstance, the head may lean forward and downward [31]. Therefore, to assist subjects with FHP, we provided support in the thoracic spine region. We modified these adjustments based on the height of Iranian students. According to data from 911 Iranian universities [32], male and female students in Iran aged 18 to 25 are, on average, 1.74 meters and 1.59 meters tall, respectively [32].

Measures

Questionnaire

The international physical activity questionnaire-short form (IPAQ-SF) was utilized to evaluate the physical activity levels of the included participants. This assessment evaluated the physical activity undertaken in the week prior. This questionnaire’s validity (0.85) and reliability (0.70) in Persian were both confirmed [33]. To translate the IPAQ data to MET-min/week for each type of activity, the number of minutes spent on each activity category was multiplied by the specific metabolic equivalent (MET) score for that activity. The energy cost of each activity type is considered when calculating the MET score. One MET is roughly equivalent to 3.5 mL O2/kg/min in adults and measures energy expenditure while at rest. According to the IPAQ’s scoring system, physical activity levels were ultimately divided into three levels: light, moderate, and vigorous [34, 35].

Moreover, we used the depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) to assess the mental health of participants. This questionnaire has high reliability (Cronbach’s α>0.90) and demonstrated validity across diverse populations [36]. According to reports, its Cronbach’s α scores for depression, anxiety, and stress in the Iranian population were 0.77, 0.79, and 0.78, respectively [37]. Each category of mental health, comprising depression, anxiety, and stress, is covered by 7 items in this questionnaire. The ratings for the responses range from zero (“did not apply to me at all”) to three (“applied to me very much or most of the time”) on a Likert scale. The total score for each scale was determined by summing the scores for the relevant items and multiplying by two, resulting in a possible range of 0 to 42. Participants were categorized into five levels of depression, anxiety, and stress: normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. To assess the severity of each sub-scale, we employed the cut-off scores suggested by Lovibond and Lovibond [36]. Consequently, scores ≥21, 15, and 26 (respectively) for depression, anxiety, and stress were deemed serious. A higher score on each scale indicated a more severe mental condition [36, 38].

Test paradigm: Response inhibition test

In our research, we evaluated inhibitory control using the stop signal paradigm (Schuhfried GmbH, Austria) (form S1; [39]). A set of arrows pointing either left or right is displayed on a screen in this task [40]. In order to respond, participants must press the "5" key to indicate a left arrow or the "6" key to indicate a right arrow as rapidly as possible (Figure 1). Each arrow is shown for one second, followed by a one-second blank screen. The test consists of a total of 200 trials, divided into two parts of 100 trials each.

Stop signal delay (SSD) and stop signal reaction time (SSRT) are two of the four main factors measured by the stop signal paradigm. The SSRT measures how long it takes to suppress a response after it has been presented. The interval between the display of the go stimulus and the stop signal is referred to as the SSD [41]. Furthermore, records were kept of commission errors, which are incorrect responses to go trials, and omission errors, which are missed responses to go trials.

fNIRS measurement

In this work, we employed the Oxymap124 fNIRS system of the University of Tehran. The Oxymap124, which is a continuous wave (CW) fNIRS device, operates at two wavelengths of 730 and 850 nm with a sampling rate of 10 Hz. Two optodes were applied to the forehead using double-sided medical adhesive, with the midpoint of each probe centered on the Fp1/Fp2 locations according to the International 10-20 system (Figure 1). An elastic cap was then placed over the optodes on the head to shield them from ambient light. The PFC was chosen as the location for signal recording because it is connected to higher cognitive and attention activities [42]. The source-detector distance of each Optod was set to 25 mm. Both fNIRS channels were categorized as belonging to Brodmann area 10 (BA 10), which contributes to attention, inhibitory control [43], and prefrontal oxygenation [44]. Numerous NIRS investigations document changes in brain activity (BA) 10's hemodynamics, with the majority conducted on healthy individuals. In the data provided, the distribution of medial and lateral alterations appears to be equal. While medial BA 10 was reported to exhibit oxygenated deactivations after pain (5/5 studies), lateral BA 10 is more frequently linked to oxygenation activations (4/5 studies) [44].

In accordance with probabilistic anatomical craniocerebral correlation [45], probes were projected to belong to the left and right medial PFC (MPFC). To prevent motion artifacts, participants were asked to minimize head movements during signal recording [42, 46].

Procedure

The craniovertebral angle (CVA), determined by the position of the head when viewed laterally at the seventh cervical (C7) vertebra, was measured to determine whether the patients had FHP. This angle is obtained by drawing a line through the C7 vertebra’s spinous process on the horizontal plane and connecting it to the tragus of the ear with another line (Figure 1). The angle decreases as the head position is perceived to be more forward [47]. The subjects focused on a fixed point that corresponded to their eye height while maintaining an upright position and relaxing both arms alongside their trunks. The locations of the tragus of the ear and the spinous process of the C7 vertebra were noted to accurately assess the position when taking a photograph. A digital camera mounted on a tripod was then placed 80 cm from the participants while they stood next to the wall in a specified area. Each participant’s C7 vertebra served as the reference point for the height adjustment of the camera. Participants were instructed to stand naturally and securely with their arms above their heads three times while concentrating on an imagined spot on the wall. A tester took three pictures from the lateral side after a 5-second interval. The CVA was ultimately determined by transferring the selected picture to a computer and utilizing ImageJ software (Rasband, USA) [48]. A CVA of less than 48–50 degrees is considered indicative of FHP, with a smaller CVA suggesting a greater degree of FHP. In this study, the CVA cut-off was set at 48; patients with a CVA of 48 or less were classified as having FHP, while those with a CVA of 48 or more were classified as healthy [31]. Thus, the CVA criterion for FHP in this study was established at ≥48°.

Previous research on cognitive task performance has demonstrated that effects may not be present when respondents are informed about the context of the investigation [10]. Therefore, our participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study at the end of the experiment. Testing was conducted at the same time of day for all participants. Each participant completed the task twice: once in an upright posture and once in FHP. To control for order effects, participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Half of the participants began the task in an upright posture and then switched to FHP, while the other half started in FHP and then switched to the upright posture. A ten-minute rest period was provided between the two postures to prevent participants’ mental states from adapting to the cognitive task.

First, participants were required to complete the IPAQ-SF and DASS in their considered posture for the task. This means that before beginning the cognitive task and fNIRS measurement, participants had been in the altered posture for approximately 5 minutes. Following the instructions, participants completed the stop-signal task while fNIRS measurements were taken in a quiet and dimly lit room.

fNIRS data pre-processing

The fNIRS signals captured in the present study were pre-processed using the HomER3 package [49], which was implemented in MATLAB software, version R2020a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). We applied a 4th-order Butterworth band-pass filter with a pass range of 0.01-0.9 Hz to eliminate physiological artifacts while preserving functional data [50, 51]. Motion artifacts were corrected using wavelet-based techniques available in HomER3 [52, 53].

To eliminate slow signal drifts, baseline drifts were adjusted using a high-pass filter [52]. For additional analysis, the raw light intensity data were transformed to optical density [49]. Using the modified Beer-Lambert law, the fNIRS device automatically converted optical density to changes in concentrations of OXY-Hb and Deoxy-Hb.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 24.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA). The homogeneity of variances and normality of the distribution of the parameters were tested using Levene’s and Shapiro-Wilk’s tests, respectively. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed in order to assess the stop signal task and hemodynamic changes. Our experimental design determined posture as the within-subject factor, representing the time variable with two levels: upright and FHP. Additionally, gender was the between-subject factor, with participants grouped into male and female categories. Partial eta squared was used as an effect size. Statistical significance was set at the level of P<0.05.

Results

Participants’ demographics

The demographic data presented in Table 1 show key differences between genders in physical characteristics and health assessments. Significant differences in physical activity levels were seen between genders. Compared to females (38.4%), a considerable percentage of males (57.1%) reported high physical activity levels. On the other hand, 71.4% of males and 61.5% of females reported normal depression and anxiety levels, while similar proportions reported typical stress levels.

This contextual data assures that the participants’ backgrounds will be appropriately considered when interpreting the results. Furthermore, the previously mentioned demographic findings underscore significant differences and similarities between male and female participants, providing a basis for comprehending plausible impacts on research outcomes.

Cognitive performance

Stop signal reaction time

Both male and female participants were tested for the SSRT in their FHP and upright positions. There were no significant gender-posture interactions (P=0.800) or differences in SSRT across the two postures (P=0.101, partial η2=0.003). This suggests that the speed of the inhibition process was not substantially affected by either gender or posture (Table 2).

SSD

In addition, the mean SSD for both genders and postures was assessed. The findings revealed no gender or statistically significant differences in SSD between the forward and upright head postures (P=0.150, partial η2=0.053). This implies that SSD did not vary based on the individual’s gender or posture (Table 2).

Error Analysis

We examined commission and omission errors to evaluate the participants’ accuracy. In the FHP (Mean±SD, 9.74±5.57) compared to the upright posture (Mean±SD, 10.7±5.04), there were fewer commission errors; however, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.206, η2=0.040). The number of commission errors in each posture was not substantially influenced by gender (P=0.318).

Gender did not have a significant effect on omission errors (P=0.402), and there were no significant differences between postures (P=0.193, η2=0.028). These results imply that neither gender nor posture had discernible effects on the error rates (Table 2).

These results demonstrate that posture and gender did not significantly impact cognitive task performance regarding SSRT, SSD, and error rates.

Hemodynamic changes

To analyze hemodynamic changes, we measured the levels of oxygenated hemoglobin (OXY-Hb) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (Deoxy-Hb) in both upright and FHPs for male and female subjects. Different sitting postures and genders yielded different OXY-Hb and Deoxy-Hb values.

OXY-Hb

Gender and posture differences were observed in the mean OXY-Hb values. The mean OXY-Hb level in the upright posture was 4.1±1.8 for male participants and 3.2±0.8 for female participants (Figure 2). The OXY-Hb levels in the FHP were 2.7±1.3 in males and 3.8±0.8 in females. It appears that posture did not significantly affect OXY-Hb levels across genders, as revealed by the ANOVA results, which showed no significant interaction effect for OXY-Hb values (P=0.321, partial η2=0.002).

Deoxy-Hb

Deoxy-Hb levels were found to follow different patterns depending on gender and sitting posture. In the upright posture, the mean deoxy-Hb level for male participants was 4.0±1.2, whereas that for female participants was somewhat lower at 3.0±1.0. In contrast, females exhibited a higher deoxy-Hb level of 4.3±1.1 in the FHP compared to males, who had a Deoxy-Hb level of 2.9±0.9. When considering the role of gender, the main effect of posture on Deoxy-Hb values was significant (P<0.01, partial η2=0.502), indicating that women performed the task with higher deoxy-Hb values in the FHP, which was not observed in men. Additionally, there was a significant difference in deoxy-Hb levels between males and females across different sitting postures (Table 3).

As illustrated in Figure 2, OXY-Hb values were generally higher in the upright posture (Mean±SD, 3.7±1.52) compared to the FHP (Mean±SD, 3.32±1.2). In contrast, the FHP (Mean±SD, 3.61±1.23) exhibited more intense deoxy-Hb values than the upright position (Mean±SD, 3.55±1.24). These results demonstrate how gender and posture significantly influence deoxy-Hb levels during the task.

Discussion

Our findings indicated that while short-term alterations in sitting posture do not significantly impact inhibition control or overall cognitive performance, gender differences in prefrontal oxygenation responses are evident. Specifically, females exhibited significantly higher deoxy-Hb levels in the FHP than males, suggesting distinct neural and vascular adaptations to postural changes. The main conclusions are as follows: 1) There is a statistically significant difference in Deoxy-Hb values between males and females (P<0.01); 2) Higher OXY-Hb levels were observed in the upright posture, but this was not statistically significant (P=0.321); and 3) No significant difference in task performance was found between the two sitting postures in terms of processing speed and accuracy.

Our findings indicated that posture alone may not directly impact cognitive performance, as evidenced by the lack of significant differences in processing speed and accuracy between the upright and FHPs during the stop-signal task. Regarding processing speed, previous work revealed that subjects in an upright position processed more objects in the d2-R task compared to a stoop sitting posture [10]. Nevertheless, in our experiment, no significant differences were observed in the processing speed in either the male or female participants while performing the stop-signal task. Since they applied a different cognitive task, our results are not directly comparable. We propose various theories for why other results differ from ours. One factor could be that earlier research predicted the advantageous benefits of upright posture on subject processing speed based on the number of processed items during the d2-R test [10]. Due to the differences in object processing and speed in the current inhibition task, it is possible that findings related to processing objects cannot be easily translated to speed processing as measured in the stop-signal task.

Meanwhile, we calculated the speed of processing by considering SSRT and SSD. The SSRT is the amount of time needed to stop the reaction triggered by the signal. The SSD, which is the period during which participants successfully withhold their response 50% of the time, is subtracted from the average response time to go trials to derive this inference [54]. Also, the SSD is the amount of time that passes after the arrow is displayed before the beep is heard. Using a step-by-step process, the task modifies the SSD based on performance. The SSD is reduced, making it easier on the subsequent trial when a person fails to suppress their response after failing to react to a stop signal. Conversely, the SSD is increased, raising the challenge in the following trial when the individual effectively blocks their button click in response to the stop signal [54]. By deducting SSD from the completion time, SSRT can be determined [41].

Furthermore, contrary to our predictions, there are no significant variations in the number of errors and processing accuracy between the two sitting postures in the present inhibition test. Surprisingly, in a cross-sectional study of 82 participants conducted in Germany, there was no significant difference in processing accuracy between stooped sitting posture and upright posture. Specifically, in that study, participants did not perform less accurately in an upright sitting position (Mean±SD, 10.25±9.60) than when stooped (Mean±SD, 10.14±7.42) (P=0.477). In the current study, we could not find any significant effect of posture on participants’ error analysis. Thus, it seems we should consider other possibilities for the interaction between posture and cognitive function. For instance, it is possible that posture influences attitudes and metacognitive thinking, which in turn affects cognitive performance [10]. Participants who sat in an upright posture reported feeling substantially more proud after receiving positive performance-related comments than subjects who slouched [55]. Similarly, another study indicated that participants in upright postures had more confidence in their thoughts than those in stooped positions [56].

It has been proposed that physiological changes occur as a result of an alteration in posture [10]. For instance, it has been demonstrated that an upright posture enhances electroencephalographic (EEG) arousal and focused attention, implying that postural adjustments can be beneficial in preventing fatigue in sleep-deprived individuals [57]. Furthermore, the upright participants exhibited a greater pulse pressure response throughout the stressor and recovery phases those in a slumped position [19]. During the stress task, individuals in the upright position experienced greater pulse pressure, which was sustained during the recovery time. These findings represent higher physiological arousal in the upright group compared to slumped group [10, 19]. However, our findings are not directly comparable to those of these investigations because they utilized a different task and a different postural approach. The current study showed no significant differences in prefrontal oxygenation between the two different sitting postures while performing a stop-signal task.

However, participants in upright posture exhibited higher OXY-Hb values than those in the FHP, which is in line with similar findings. This implies that sitting posture can significantly influence PFC oxygenation levels. According to studies, maintaining an upright posture can improve cerebral blood flow and oxygenation by improving cervical spine alignment, which lowers vascular resistance and encourages more effective blood circulation. Additionally, keeping the body upright may aid in respiration, potentially resulting in increased oxygen levels and, ultimately, higher OXY-Hb values. It is important to note that the impact of sitting posture on prefrontal brain oxygenation was only observed in the current study. This result is consistent with findings indicating that sustained exposure may be required to notice more severe effects and that brief posture alterations may not be adequate to produce significant changes in brain oxygenation. The minimal effects observed in our study may also be explained by individual differences in physiological adaptability and baseline cognitive function, which may reduce the impact of posture on brain oxygenation.

However, the significant difference in Deoxy-Hb values between males and females in the FHP was an especially notable observation, as females showed greater amounts. The difference in hemodynamic response between both genders highlights the need for more investigation into how sitting posture affects brain oxygenation and cognitive function differently in each gender. Females' greater Deoxy-Hb levels during the FHP may indicate different vascular or metabolic reactions to postural changes, which may be mediated by differences in hormones or anatomy [58]. This physiological reaction unique to gender may affect cognitive function, indicating the need for specialized cognitive therapies and ergonomic suggestions [59]. For example, females might benefit more from interventions that address FHP to optimize cognitive function and brain oxygenation.

Taking these gender differences into consideration, future studies should examine the long-term impact of posture on cognitive function as well as the underlying physiological mechanisms. A greater understanding of the connections between posture, cognitive function, and brain oxygenation may be achieved by extending the duration of posture exposure and utilizing a variety of cognitive tasks.

Conclusion

Within the confines of this study, significant differences were observed in deoxy-Hb levels between males and females across different sitting postures. However, overall, sitting posture did not significantly influence participants' inhibitory control abilities or prefrontal activity. The interaction between gender and sitting posture suggests potential differences in the effects on cognitive processes between males and females. It is plausible that the limited duration of sitting posture exposure may have mitigated substantial changes in cognitive performance or brain oxygenation. Future research should consider longer intervention durations and a more thorough exploration of potential confounding variables.

These findings contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the multifaceted elements that affect cognitive strategies and brain activity. While our observations do not yield definitive effects, they underscore the complexity of the relationship between sitting postures and inhibition control, providing valuable insights for future investigations.

Limitations and directions

The lack of significant differences in task performance and prefrontal oxygenation between the two sitting postures supports the theory that the short sitting duration in this test may not be sufficient to cause significant changes in brain oxygenation or cognitive function. The effects of sitting posture on prefrontal brain activity and inhibition control may also need longer exposure times or particular interventions to become noticeable. In addition, various factors, including individual differences in comfort and alternative postures, may have affected the outcomes.

These findings contribute to our understanding of the complex relationship between sitting postures, cognitive characteristics, and brain activity. They suggest that while sitting posture may have theoretical implications for cognitive performance and brain oxygenation, its practical significance in a short-term context can be limited.

Future studies in this area need to take several factors into account. First, extended exposure to specific sitting postures and cognitive interventions (e.g. ergonomic adjustments) may help clarify whether more significant effects develop over time. Investigating how an individual’s decisions and habits related to their sitting posture affect their cognitive abilities and mental traits may also yield insightful results..

Ultimately, this study found no significant differences in prefrontal oxygenation or cognitive function between participants in FHP and upright posture during a brief Stop-signal task. These results imply that while sitting posture remains an intriguing area of study, its effects on inhibition control and prefrontal brain activity may be minimal, necessitating further research under particular conditions and over longer periods.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sport Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SSRC.REC.1402.322).All participants signed a written informed consent form.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design and data collection: Mohammad Salsali, Hashem Piri, Kamaledin Setarehdan and Fateme Soltani; Drafting of the manuscript and made critical revision: Mohammad Salsali, Rahman Sheikhhoseini, Kamaledin Setarehdan, Mojtaba Soltanlou, Mohammadreza Ghasemian, Hashem Piri and Sajjad Abdollahi; Final Approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of Allameh Tabataba'i University for allowing the researchers to conduct this research in this laboratory.

References

- Rebar AL, Vandelanotte C, Van Uffelen J, Short C, Duncan MJ. Associations of overall sitting time and sitting time in different contexts with depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2014; 7(2):105-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.mhpa.2014.02.004]

- Bibbo D, Carli M, Conforto S, Battisti F. A sitting posture monitoring instrument to assess different levels of cognitive engagement. Sensors (Switzerland). 2019; 19(3):455. [DOI:10.3390/s19030455] [PMID]

- Quka N, Stratoberdha D, Selenica R. Risk factors of poor posture in children and its prevalence. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 2015; 4(3):97-102. [DOI:10.5901/ajis.2015.v4n3p97]

- Brianezi L, Cajazeiro DC, Maifrino LBM. Prevalence of postural deviations in school of education and professional practice of physical education. Journal of Morphological Sciences. 2011; 28(1):35-6. [Link]

- Vijayalakshmi T, Subramanian Sk, Dharmalingam A, Itagi ABH, Mounian SV, Loganathan S. A short term evaluation of scapular upper brace on posture and its influence on cognition and behavior among adult students. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2022; 16(April):101077. [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2022.101077]

- Jung SI, Lee NK, Kang KW, Kim K, Lee DY. The effect of smartphone usage time on posture and respiratory function. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016; 28(1):186-9. [DOI:10.1589/jpts.28.186] [PMID]

- Oh HJ, Song GB. Effects of neurofeedback training on the brain wave of adults with forward head posture. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016; 28(10):2938-41. [DOI:10.1589/jpts.28.2938] [PMID]

- Kim SY, Kim NS, Kim LJ. Effects of cervical sustained natural apophyseal glide on forward head posture and respiratory function. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2015; 27(6):1851-4. [DOI:10.1589/jpts.27.1851] [PMID]

- Muehlhan M, Marxen M, Landsiedel J, Malberg H, Zaunseder S. The effect of body posture on cognitive performance: A question of sleep quality. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014; 8:171. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00171] [PMID]

- Awad S, Debatin T, Ziegler A. Embodiment: I sat, I felt, I performed - Posture effects on mood and cognitive performance. Acta Psychologica. 2021; 218:103353. [DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103353] [PMID]

- Cohen RG, Vasavada AN, Wiest MM, Schmitter-edgecombe M. Mobility and Upright Posture Are Associated with Different Aspects of Cognition in Older Adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2016; 8:1-8. [DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2016.00257]

- Ahn H Il, Teeters A, Wang A, Breazeal C, Picard R. Stoop to conquer: Posture and affect interact to influence computer users’ persistence. In: Paiva ACR, Prada R, Picard RW, editors. Affective computing and intelligent interaction. ACII 2007. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4738. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-74889-2_51]

- Xie C, Alderman BL, Meng F, Ai J, Chang YK, Li A. Acute High-Intensity Interval Exercise Improves Inhibitory Control Among Young Adult Males With Obesity. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:1291. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01291] [PMID]

- Diamond A. Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2013; 64:135-68. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750] [PMID]

- Ludyga S, Mücke M, Colledge FMA, Pühse U, Gerber M. A combined EEG-fNIRS Study investigating mechanisms underlying the association between aerobic fitness and inhibitory control in young adults. Neuroscience. 2019; 419:23-33.[DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.08.045] [PMID]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Self‐Regulation, Ego Depletion, and Motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2007; 1(1):115-28. [DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x]

- Risko EF, Gilbert SJ. Cognitive Offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2016; 20(9):676-88. [DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.002] [PMID]

- Veenstra L, Schneider IK, Koole SL. Embodied mood regulation: The impact of body posture on mood recovery, negative thoughts, and mood-congruent recall.Cognition & Emotion. 2017; 31(7):1361-76. [DOI:10.1080/02699931.2016.1225003] [PMID]

- Nair S, Sagar M, Sollers J 3rd, Consedine N, Broadbent E. Do slumped and upright postures affect stress responses? A randomized trial. Health Psychology . 2015; 34(6):632-41. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000146] [PMID]

- Wilson VE, Peper E. The effects of upright and slumped postures on the recall of positive and negative thoughts. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2004; 29(3):189-95. [DOI:10.1023/B:APBI.0000039057.32963.34] [PMID]

- Quaresima V, Ferrari M. A Mini-Review on Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS): Where Do We Stand, and Where Should We Go? Photonics. 2019; 6(3):87. [DOI:10.3390/photonics6030087]

- Ferguson HJ, Brunsdon VEA, Bradford EEF. The developmental trajectories of executive function from adolescence to old age. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):1382. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-80866-1] [PMID]