Thu, Feb 19, 2026

Volume 16, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PTJ 2026, 16(1): 63-72 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Piri E, Jafarnezhadgero A, Stalman A. Effect of a 12-week Physical Activity Program on Motor Skills in Overweight Schoolchildren. PTJ 2026; 16 (1) :63-72

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-735-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-735-en.html

1- Department of Sports Biomechanics, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden.

2- Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden.

Full-Text [PDF 532 kb]

(582 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1317 Views)

Full-Text: (152 Views)

Introduction

Epidemiological studies suggest a sharp rise in the global prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents [1, 2]. Recent epidemiological data indicate that childhood obesity has reached alarming levels, affecting over 19-25% of children and adolescents globally, with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and musculoskeletal disorders later in life [2]. Due to negative perceptions, these individuals may experience difficulties in forming friendships and participating in social activities, leading to a sense of isolation [2]. This represents a significant public health concern, as affected individuals frequently face stigma, which can result in diminished self-esteem and social isolation [1].

Children have a natural urge to move and want to be as active as possible [3]. In today’s living conditions, it is observed that children’s movement areas are restricted and outdoor play areas are gradually decreasing. With developing technology, children have become individuals who live more in closed areas and spend time with technological play materials, which can cause various posture disorders, weight gain due to physical inactivity, and coordination disorders [1]. Physical activity decreases with age throughout childhood and adolescence [4]. Physical activity offers a wide range of activities that include many movements and muscle groups. Many studies have shown that low physical activity levels are associated with a decrease in motor skills in children and adolescents [5, 6].

In order to support children’s motor skills and physical health development, efforts should be made to increase their participation in sports activities [7]. Basic motor skills generally develop in early childhood, and the development of sports-specific skills can be achieved through adequate physical activity [8]. The promotion of physical activity is considered a fundamental public health strategy to improve the health of individuals and communities [9]. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies confirm the relationship between physical activity and motor skills [10, 11]. Various physical activity programs have been developed to support healthy development in children [11].

Many systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies have examined physical activity and motor skill development in healthy children in detail [10, 12]. The development and implementation of physical activity interventions aimed at enhancing motor skills in children have become an increasingly important area of research [7]. In this context, it is believed that an effective physical activity program applied to children will help them acquire the expected skills more easily and positively affect their later lives.

Despite growing evidence on childhood obesity and physical activity interventions, a critical gap persists in understanding how integrated exercise programs (combining fundamental motor skills, low-intensity movements, and anaerobic training) impact the motor function and long-term physical health of overweight schoolchildren. Previous studies often focus on isolated components (e.g. aerobic exercise alone) or short-term outcomes, neglecting the synergistic effects of multifaceted interventions tailored to this population’s unique physiological and psychological needs. Furthermore, limited research exists on scalable, school-based programs that simultaneously address obesity and motor skill deficits while ensuring adherence and sustainability. We hypothesized that the 12-week physical activity program would lead to significant improvements in body composition (body mass and body mass index [BMI]) and motor skills (flexibility, balance, agility, and sprint performance) in both overweight and normal-weight children.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

Forty schoolchildren, aged 8–10 years, both with and without overweight, volunteered for this study. The participants were divided into two groups: The overweight schoolchildren group (n=20) and the normal-weight group (n=20). The sample size was estimated using the freeware tool G*Power software, version 3.1.9.2 (University of Kiel, Germany) [13].

Participants were recruited from local schools using advertisements and informational meetings with parents. Inclusion criteria for the overweight group were: i) male gender, ii) BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles according to the national reference curves developed by Rolland-Cachera et al. [14]; iii) enrollment in second or third grade, iv) participation in standard physical education classes, and v) no known medical conditions. The exclusion criteria for the overweight group included: i) BMI below the 5th percentile (underweight) or above the 99th percentile (severe obesity), ii) non-participation in standard physical education classes, and iii) incomplete data related to BMI, age, or physical activity level. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents.

The exclusion criteria for the normal-weight group included: i) not participating in the school’s standard physical education classes or being outside the second or third grade; ii) children with a BMI below the 5th percentile (underweight) or above the 99th percentile (severe obesity) were not eligible for this study. Overweight classification was determined based on a BMI falling between the 85th and 94th percentiles. This classification is based on Iran’s national reference curves, which are consistent with international standards, such as those from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, due to population-specific differences, national curves were used to ensure accuracy and comparability within the study population; iii) Missing or incomplete data related to BMI, age, or physical activity level, and iv) Parental or personal refusal to participate in the study. All participants gave their written informed consent before the study began. Around 90% of the children came from middle-income families, representing a combined socioeconomic and ethnic background. Eligible participants also provided written informed consent. This study was planned based on an experimental design to examine the effects of a 12-week physical activity program on motor skills in children aged 8-10 years. Subjects were selected using a simple random sampling method and were included voluntarily. In this context, the program’s effects on motor skills were evaluated by measuring participants twice before and after the determined physical activity program. All applied measurements were taken at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili Laboratory. Participants’ measurements were conducted with the same equipment, by the same researcher, and at the same times to eliminate circadian rhythm, method, device, and physiological differences. Participants were given a 5-10 minute warm-up exercise before the measurements and a 5-10 minute stretching exercise afterward, and each participant underwent the tests twice [15].

Data collection tools

Anthropometric measurements: Participants’ body weight (BW) was measured using a body composition analyzer (Tanita MC-780-MA, Japan), with a sensitivity of ±0.1 kg. Height (BU) was measured using a portable stadiometer (Holtain brand), with a sensitivity of ±1 mm. Measurements were taken while participants stood in anatomical posture, wearing sportswear and barefoot. BMI was calculated by dividing BW (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters) (Equation 1):

1. BMI=Weight (kg)/Height (m²)

Sprint performance: The sprint performances of the participants were evaluated through 5, 10, 20, and 30-meter sprint tests (S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m). Sprint times at each distance were obtained using 2D video analysis. High-speed digital images for this analysis were captured with an iPhone 12, which features a 16-core A14 Bionic processor and a 12 MP camera system. The images were recorded in 1080 p HD quality at 240 frames per second to capture the participants’ movements across different distances. The iPhone 12 was mounted on a tripod positioned 18 meters from the sprint area to ensure it could capture all the distances. The digital images were transferred to the free, open-source digitization software, Kinovea 0.9.5, which has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability for 2D motion analysis when used with proper calibration and standardized protocols, making it a suitable tool for biomechanical assessments in both research and practical applications. A parallax correction method was applied to accurately measure intermediate times as participants crossed different target distances [16].

Active jump height: The active jump heights of participants were measured using the mobile application “jumping record,” which enables high-speed video analysis. A standardized protocol was followed for the active jump height test [17]. Video recordings were taken by positioning the iPhone 12 on a tripod set 1.5 meters away from the predetermined measurement point to ensure a consistent setup.

Sit-and-reach flexibility test: A standardized protocol was followed for the sit-and-reach flexibility test [18]. All participants were instructed to sit on an exercise mat in a long sitting position with their shoes off, the soles of their feet touching the bench, and their knees straight. They were then asked to lean forward on the bench and stretch as far as possible.

Flamingo balance test: A predetermined standard protocol was adhered to for the Flamingo balance test [19]. If balance was lost or if the foot touched the ground, it was recorded as a fall score. A higher score indicates more severe balance difficulties.

Physical activity intervention: This eight-week physical activity intervention was designed to enhance fundamental movement skills and gross motor competencies in children aged 8–10 years. The program integrated a structured progression of exercises targeting key motor domains, including locomotor skills (e.g. variable-speed running, multidirectional jumps, and agility drills with angular direction changes), stability skills (e.g. dynamic balance exercises, center-of-gravity stabilization, and posture control), and object-control skills (e.g. reaction drills using colored balls and coordinated limb movements with equipment) [20, 21]. To optimize neuromuscular adaptation, the intervention incorporated reciprocal inhibition drills involving agonist-antagonist coordination exercises for both single- and multi-joint movements. These included activities, such as kickboxing-based punch/kick combinations with contralateral limb synchronization, designed to enhance neuromuscular efficiency. Concurrently, kinesthetic awareness training was integrated through multi-limb movement sequences, exemplified by simultaneous hand-foot-ball coordination tasks requiring right-left alternations [22].

Session design prioritized sustained engagement by implementing gamification strategies, such as task-variable parkour circuits, interactive team challenges, and real-time feedback games, all structured to maintain participant motivation and program adherence [23]. The weekly regimen comprised 7–8 hours of supervised training, delivered across five daily sessions lasting 1.5–2 hours each. Training intensity followed an 80:20 polarized distribution: Approximately 80% of sessions focused on low-intensity aerobic components, including dynamic warm-ups, skill acquisition drills, and recovery-focused activities, while the remaining 20% targeted anaerobic adaptations through high-intensity interval games and power-oriented exercises [24]. This balanced approach was designed to foster the development of children’s motor skills in an engaging and motivating manner.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.3.1. The normality of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram visualization. Data are presented as Mean±SD. To examine differences in the dependent variables after the 12-week physical activity program while controlling for baseline values, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted. The pre-test scores were included as covariates to adjust for initial differences between groups. ANCOVA was utilized to perform the analysis, and the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was tested before the analysis. When ANCOVA indicated significant effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni adjustment. Additionally, effect sizes were reported using partial eta squared (η²), interpreted as small (η²≥0.01), medium (η²≥0.06), and large (η²≥0.14) [25]. Percentage changes (%Δ) between pre- and post-intervention measurements were also calculated. The significance level was set at α<0.05 for all analyses.

Results

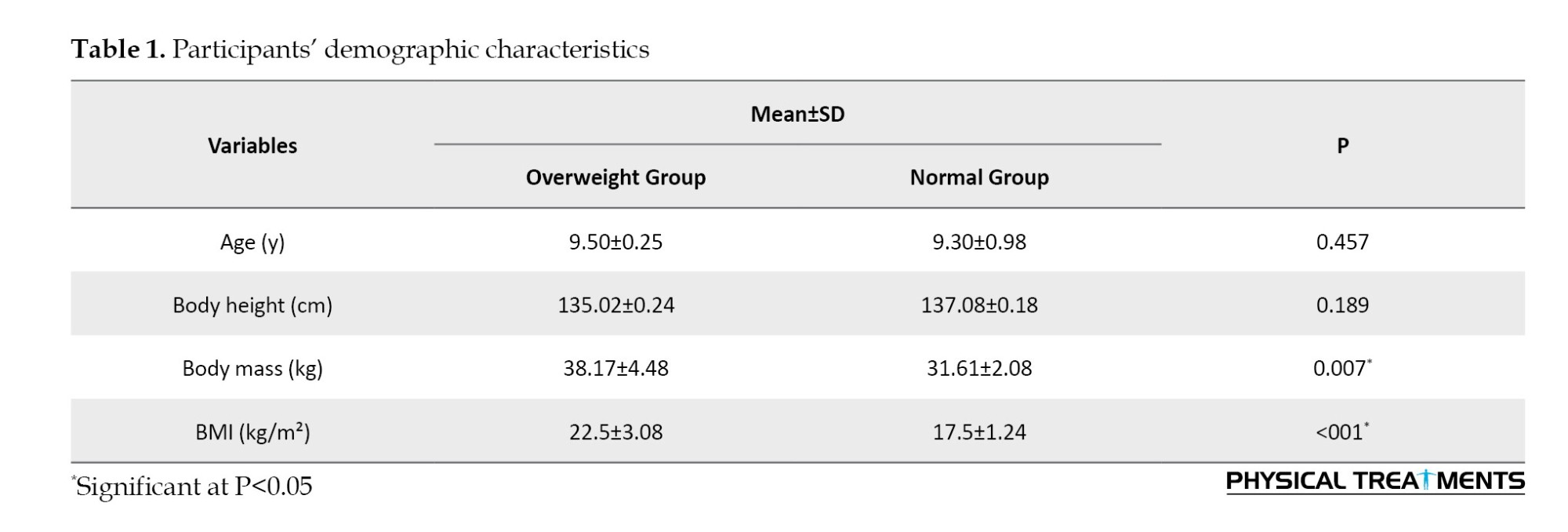

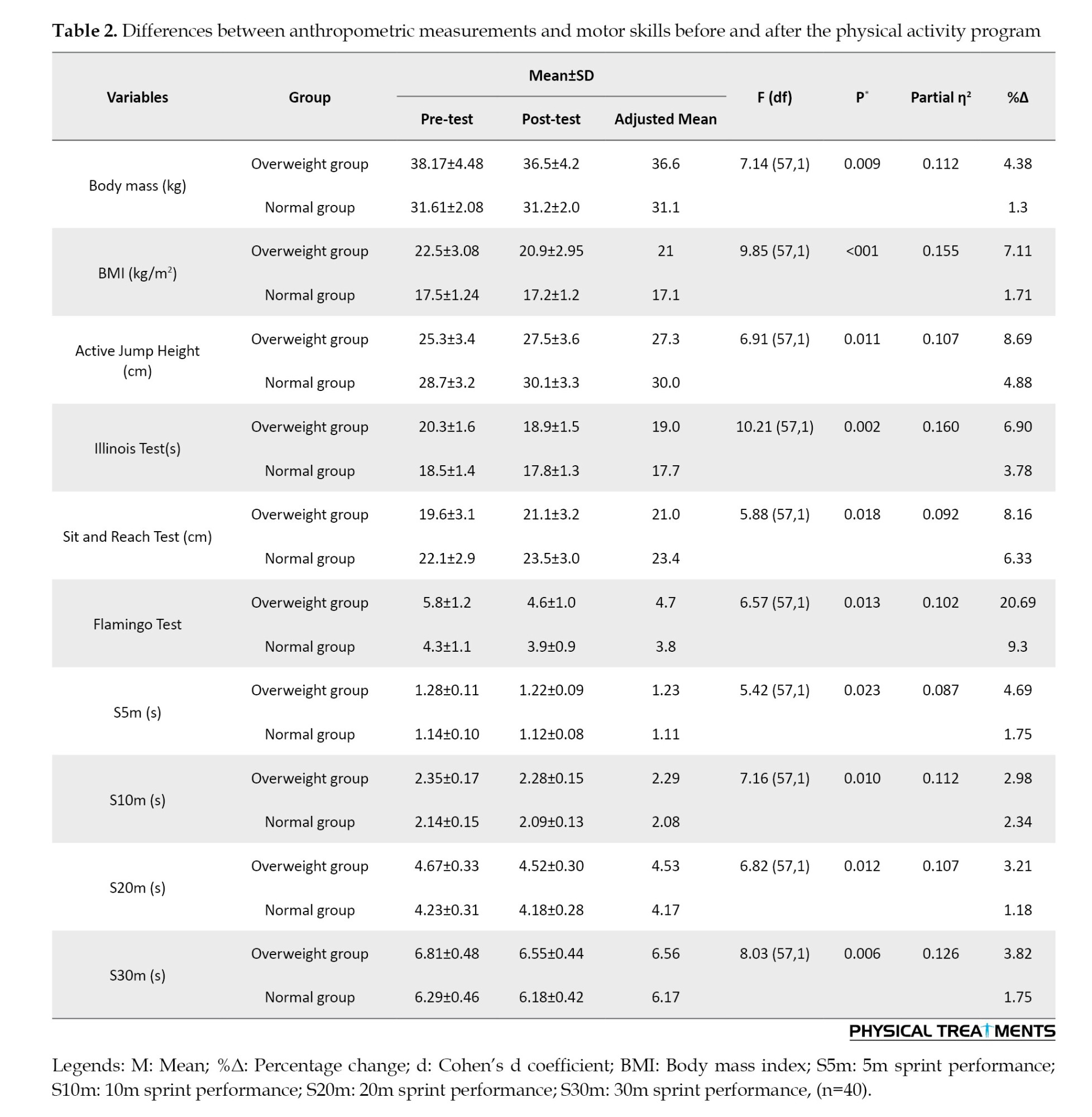

Descriptive characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. A comparison of baseline characteristics between the overweight and normal-weight groups revealed no significant differences for most variables, including height (P=0.457), active jump height (P=0.112), Illinois agility test performance (P=0.189), and sit-and-reach flexibility (P=0.231). However, as expected, significant differences were observed in body mass (P<0.001) and BMI (P<0.001), reflecting the classification criteria for the two groups.

There was a statistically significant difference between the groups in height, BMI, active jump height, Illinois agility test, sit-and-reach flexibility test, flamingo balance test, as well as the times for the S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m tests before and after the program.

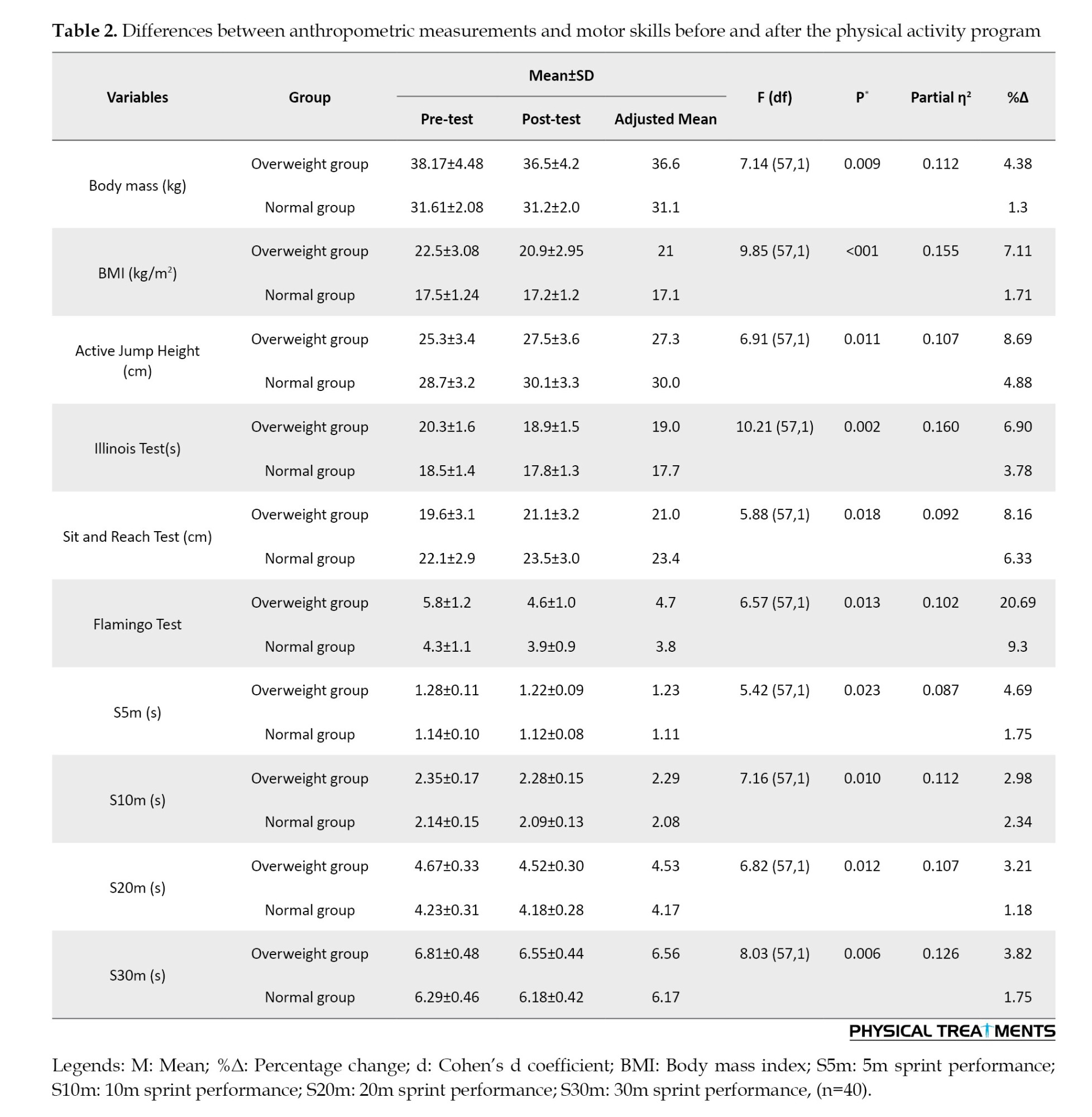

The overweight group showed a significant reduction in body mass (F=7.14, P=0.009, %Δ=4.38%) and BMI (F=9.85, P< 0.001, %Δ=3.3%), while the normal group had a smaller but still notable decrease in both measures. Active jump height improved significantly in both groups (F=6.91, P=0.011), with the overweight group showing a %Δ of 7.11% and the normal group improving by 3.89%. The Illinois test demonstrated significant improvements for both groups (F=5.47, P= 0.024), with the overweight group showing a %Δ of 5.29% and the normal group a %Δ of 3.67%. Flexibility, as measured by the sit-and-reach test, increased notably in the overweight group (F=6.81, P=0.013, %Δ=16.61%) and slightly in the normal group (%Δ=10.37%). Balance, assessed using the Flamingo test, improved significantly in the overweight group (F=4.63, P=0.038, %Δ=20.69%) and to a lesser extent in the normal group (%Δ=12.79%). Sprint performance across all distances (5m, 10m, 20m, and 30m) improved significantly in the overweight group (P<0.05 for all), with %Δ ranging from 2.98% to 8.32%, whereas the normal group also improved but with smaller percentage changes (1.17% to 3.11%).

The effect sizes (Partial η²) indicated that BMI (0.155), body mass (0.117), and sprint performances (0.112-0.126) had moderate to large effects, suggesting that the intervention had a significant impact on weight reduction, flexibility, balance, and sprint speed, particularly in overweight individuals (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of a 12-week physical activity program on children aged 8-10. The program incorporated dynamic warm-ups, balance and coordination exercises, perception and reaction drills, multi-limb movement sequences, and interactive games. Each week, it included a variety of motor skill exercises, low-intensity activities, and anaerobic-based training. The study focused on assessing changes in anthropometric characteristics, such as BW, height, and BMI, as well as performance metrics, including active jump height, agility, flexibility, balance, and sprint times for S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m.

One of the most notable outcomes of the study is the significant reduction in body mass and BMI, particularly in the overweight group. Although the normal-weight group also experienced reductions, the effects were more pronounced in the overweight group, indicating that the program was especially beneficial for weight management among children with higher initial BMI values. These findings align with previous studies suggesting that structured exercise interventions contribute to effective weight control and improved body composition in children [26]. The mechanism underlying this effect likely involves increased energy expenditure and improved metabolic efficiency due to structured exercise [27]. Higher initial BMI values may make individuals more responsive to such interventions, as excess adiposity provides a greater capacity for energy utilization [28]. Additionally, structured exercise programs can enhance muscle mass, improve insulin sensitivity, and regulate appetite, all of which contribute to more effective weight management [29]. Overweight children demonstrated greater improvements in motor skills and body composition compared to normal-weight children. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that individuals with higher initial BMI values tend to respond more favorably to structured exercise interventions due to their greater capacity for energy utilization and relative strength adaptations [28]. Moreover, the significant improvements observed in the overweight group align with findings from Ratajczak et al. [26], who reported that a 12-week combined strength and endurance training program led to notable enhancements in insulin sensitivity and reductions in body fat among overweight women. These metabolic adaptations likely contributed to the greater improvements in motor skills and physical fitness observed in our study.

The improvements in active jump height further demonstrate the program’s effectiveness in enhancing lower-body power. The overweight group showed a greater percentage increase compared to the normal-weight group, suggesting that even children with excess weight can significantly improve their muscular power with consistent physical activity. This result supports previous literature indicating that plyometric and strength-based activities incorporated into physical programs can lead to significant gains in lower-limb explosiveness [30]. The mechanism behind these improvements likely involves neuromuscular adaptations and enhanced muscle activation due to consistent training [31]. Additionally, Adamczak et al. [29] found that physical activity interventions in obese patients resulted in better perinatal outcomes, suggesting that structured exercise programs can effectively address weight management and improve overall health metrics. This supports our conclusion that tailored physical activity programs have substantial potential to address childhood obesity and enhance physical fitness, particularly in overweight populations.

Plyometric and strength-based exercises stimulate fast-twitch muscle fibers, improve motor unit recruitment, and enhance the stretch-shortening cycle efficiency, all of which contribute to greater lower-body power [32]. Additionally, the overweight group’s higher initial mass may have led to greater relative strength adaptations as their muscles adapted to repeated loading, resulting in a more pronounced improvement in jump height [33].

Agility, as measured by the Illinois agility test, also showed marked enhancements in both groups, with the overweight group improving by 5.29% and the normal group by 3.67%. This indicates that participation in structured movement-based activities can enhance quickness and coordination regardless of initial body composition. These improvements likely result from neuromuscular adaptations and increased muscle activation through consistent training [34]. Repeated exposure to dynamic drills, directional changes, and acceleration-deceleration movements strengthens motor pathways, optimizes proprioception, and increases muscle responsiveness [35]. The greater percentage improvement in the overweight group may be attributed to their initial lower baseline performance, allowing for more noticeable gains as their movement mechanics and coordination adapt to training stimuli [36]. Flexibility, assessed through the sit-and-reach test, showed the highest percentage improvement among all measured parameters. These findings suggest that flexibility training incorporated within the program effectively increased the range of motion, which is essential for injury prevention and overall functional movement [37]. The greater relative improvement in the overweight group suggests that balance exercises can have a considerable impact on postural control and coordination, particularly for children with higher body mass [38]. The mechanism behind the greater relative improvement in the overweight group likely involves the adaptation of the body’s postural control systems to the demands of balance exercises [39]. Children with higher body mass may face greater challenges in maintaining stability, which requires greater activation of core and lower-body muscles [40]. Over time, balance exercises can improve proprioception, strengthen stabilizing muscles, and enhance neural control of posture [41]. This leads to more efficient coordination and better overall postural control, with children in the overweight group experiencing more noticeable gains as their bodies adapt to the increased demands [41].

Sprint performance at all distances (5m, 10m, 20m, and 30m) significantly improved in both groups. The improvements in sprint performance can be attributed to enhanced muscle strength, coordination, and neuromuscular efficiency developed through the training program. The training program likely enhanced muscle strength, particularly in the lower body, improving power output during acceleration [42]. Research shows that psychosocial factors, including perceived competence and enjoyment, can significantly influence adherence to physical activity and subsequent performance improvements [27]. In the context of this study, the interactive games and group-based activities incorporated into the program likely fostered a sense of enjoyment and social connection, which may have contributed to the observed improvements. This is particularly relevant for overweight children, who often face stigma and reduced self-esteem [2]. By creating an engaging and supportive environment, the intervention may have boosted participants’ intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, further enhancing their physical and motor skill development.

The limitations of the study should be acknowledged: 1) The lack of long-term follow-up to assess sustained effects; 2) A small sample size (n=40), which may limit generalizability; 3) The use of iPhone-based motion analysis, which may have lower precision compared to gold-standard systems; 4) The focus solely on male participants; and 5) Potential self-selection bias among volunteers.

Conclusions

The physical activity program effectively improved both anthropometric measures (such as body mass and BMI) and motor skills (such as flexibility, balance, agility, and sprint performance) in children. The overweight group showed more significant changes across all measures, highlighting the intervention’s potential for addressing childhood obesity and enhancing overall physical fitness. These findings emphasize the importance of regular physical activity for children’s health and physical development.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code:IR.ARUMS.REC.1397.136) and adhered to the ethical guidelines of the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: AmirAli Jafarnezhadgero and Anders Stålman; Methodology, investigation, data collection and writing the original draft: Ebrahim Piri; Data analysis: Ebrahim Piri and AmirAli Jafarnezhadgero; Review & editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who volunteered for this study.

References

Epidemiological studies suggest a sharp rise in the global prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents [1, 2]. Recent epidemiological data indicate that childhood obesity has reached alarming levels, affecting over 19-25% of children and adolescents globally, with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and musculoskeletal disorders later in life [2]. Due to negative perceptions, these individuals may experience difficulties in forming friendships and participating in social activities, leading to a sense of isolation [2]. This represents a significant public health concern, as affected individuals frequently face stigma, which can result in diminished self-esteem and social isolation [1].

Children have a natural urge to move and want to be as active as possible [3]. In today’s living conditions, it is observed that children’s movement areas are restricted and outdoor play areas are gradually decreasing. With developing technology, children have become individuals who live more in closed areas and spend time with technological play materials, which can cause various posture disorders, weight gain due to physical inactivity, and coordination disorders [1]. Physical activity decreases with age throughout childhood and adolescence [4]. Physical activity offers a wide range of activities that include many movements and muscle groups. Many studies have shown that low physical activity levels are associated with a decrease in motor skills in children and adolescents [5, 6].

In order to support children’s motor skills and physical health development, efforts should be made to increase their participation in sports activities [7]. Basic motor skills generally develop in early childhood, and the development of sports-specific skills can be achieved through adequate physical activity [8]. The promotion of physical activity is considered a fundamental public health strategy to improve the health of individuals and communities [9]. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies confirm the relationship between physical activity and motor skills [10, 11]. Various physical activity programs have been developed to support healthy development in children [11].

Many systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies have examined physical activity and motor skill development in healthy children in detail [10, 12]. The development and implementation of physical activity interventions aimed at enhancing motor skills in children have become an increasingly important area of research [7]. In this context, it is believed that an effective physical activity program applied to children will help them acquire the expected skills more easily and positively affect their later lives.

Despite growing evidence on childhood obesity and physical activity interventions, a critical gap persists in understanding how integrated exercise programs (combining fundamental motor skills, low-intensity movements, and anaerobic training) impact the motor function and long-term physical health of overweight schoolchildren. Previous studies often focus on isolated components (e.g. aerobic exercise alone) or short-term outcomes, neglecting the synergistic effects of multifaceted interventions tailored to this population’s unique physiological and psychological needs. Furthermore, limited research exists on scalable, school-based programs that simultaneously address obesity and motor skill deficits while ensuring adherence and sustainability. We hypothesized that the 12-week physical activity program would lead to significant improvements in body composition (body mass and body mass index [BMI]) and motor skills (flexibility, balance, agility, and sprint performance) in both overweight and normal-weight children.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

Forty schoolchildren, aged 8–10 years, both with and without overweight, volunteered for this study. The participants were divided into two groups: The overweight schoolchildren group (n=20) and the normal-weight group (n=20). The sample size was estimated using the freeware tool G*Power software, version 3.1.9.2 (University of Kiel, Germany) [13].

Participants were recruited from local schools using advertisements and informational meetings with parents. Inclusion criteria for the overweight group were: i) male gender, ii) BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles according to the national reference curves developed by Rolland-Cachera et al. [14]; iii) enrollment in second or third grade, iv) participation in standard physical education classes, and v) no known medical conditions. The exclusion criteria for the overweight group included: i) BMI below the 5th percentile (underweight) or above the 99th percentile (severe obesity), ii) non-participation in standard physical education classes, and iii) incomplete data related to BMI, age, or physical activity level. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents.

The exclusion criteria for the normal-weight group included: i) not participating in the school’s standard physical education classes or being outside the second or third grade; ii) children with a BMI below the 5th percentile (underweight) or above the 99th percentile (severe obesity) were not eligible for this study. Overweight classification was determined based on a BMI falling between the 85th and 94th percentiles. This classification is based on Iran’s national reference curves, which are consistent with international standards, such as those from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, due to population-specific differences, national curves were used to ensure accuracy and comparability within the study population; iii) Missing or incomplete data related to BMI, age, or physical activity level, and iv) Parental or personal refusal to participate in the study. All participants gave their written informed consent before the study began. Around 90% of the children came from middle-income families, representing a combined socioeconomic and ethnic background. Eligible participants also provided written informed consent. This study was planned based on an experimental design to examine the effects of a 12-week physical activity program on motor skills in children aged 8-10 years. Subjects were selected using a simple random sampling method and were included voluntarily. In this context, the program’s effects on motor skills were evaluated by measuring participants twice before and after the determined physical activity program. All applied measurements were taken at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili Laboratory. Participants’ measurements were conducted with the same equipment, by the same researcher, and at the same times to eliminate circadian rhythm, method, device, and physiological differences. Participants were given a 5-10 minute warm-up exercise before the measurements and a 5-10 minute stretching exercise afterward, and each participant underwent the tests twice [15].

Data collection tools

Anthropometric measurements: Participants’ body weight (BW) was measured using a body composition analyzer (Tanita MC-780-MA, Japan), with a sensitivity of ±0.1 kg. Height (BU) was measured using a portable stadiometer (Holtain brand), with a sensitivity of ±1 mm. Measurements were taken while participants stood in anatomical posture, wearing sportswear and barefoot. BMI was calculated by dividing BW (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters) (Equation 1):

1. BMI=Weight (kg)/Height (m²)

Sprint performance: The sprint performances of the participants were evaluated through 5, 10, 20, and 30-meter sprint tests (S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m). Sprint times at each distance were obtained using 2D video analysis. High-speed digital images for this analysis were captured with an iPhone 12, which features a 16-core A14 Bionic processor and a 12 MP camera system. The images were recorded in 1080 p HD quality at 240 frames per second to capture the participants’ movements across different distances. The iPhone 12 was mounted on a tripod positioned 18 meters from the sprint area to ensure it could capture all the distances. The digital images were transferred to the free, open-source digitization software, Kinovea 0.9.5, which has demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability for 2D motion analysis when used with proper calibration and standardized protocols, making it a suitable tool for biomechanical assessments in both research and practical applications. A parallax correction method was applied to accurately measure intermediate times as participants crossed different target distances [16].

Active jump height: The active jump heights of participants were measured using the mobile application “jumping record,” which enables high-speed video analysis. A standardized protocol was followed for the active jump height test [17]. Video recordings were taken by positioning the iPhone 12 on a tripod set 1.5 meters away from the predetermined measurement point to ensure a consistent setup.

Sit-and-reach flexibility test: A standardized protocol was followed for the sit-and-reach flexibility test [18]. All participants were instructed to sit on an exercise mat in a long sitting position with their shoes off, the soles of their feet touching the bench, and their knees straight. They were then asked to lean forward on the bench and stretch as far as possible.

Flamingo balance test: A predetermined standard protocol was adhered to for the Flamingo balance test [19]. If balance was lost or if the foot touched the ground, it was recorded as a fall score. A higher score indicates more severe balance difficulties.

Physical activity intervention: This eight-week physical activity intervention was designed to enhance fundamental movement skills and gross motor competencies in children aged 8–10 years. The program integrated a structured progression of exercises targeting key motor domains, including locomotor skills (e.g. variable-speed running, multidirectional jumps, and agility drills with angular direction changes), stability skills (e.g. dynamic balance exercises, center-of-gravity stabilization, and posture control), and object-control skills (e.g. reaction drills using colored balls and coordinated limb movements with equipment) [20, 21]. To optimize neuromuscular adaptation, the intervention incorporated reciprocal inhibition drills involving agonist-antagonist coordination exercises for both single- and multi-joint movements. These included activities, such as kickboxing-based punch/kick combinations with contralateral limb synchronization, designed to enhance neuromuscular efficiency. Concurrently, kinesthetic awareness training was integrated through multi-limb movement sequences, exemplified by simultaneous hand-foot-ball coordination tasks requiring right-left alternations [22].

Session design prioritized sustained engagement by implementing gamification strategies, such as task-variable parkour circuits, interactive team challenges, and real-time feedback games, all structured to maintain participant motivation and program adherence [23]. The weekly regimen comprised 7–8 hours of supervised training, delivered across five daily sessions lasting 1.5–2 hours each. Training intensity followed an 80:20 polarized distribution: Approximately 80% of sessions focused on low-intensity aerobic components, including dynamic warm-ups, skill acquisition drills, and recovery-focused activities, while the remaining 20% targeted anaerobic adaptations through high-intensity interval games and power-oriented exercises [24]. This balanced approach was designed to foster the development of children’s motor skills in an engaging and motivating manner.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using R software, version 4.3.1. The normality of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histogram visualization. Data are presented as Mean±SD. To examine differences in the dependent variables after the 12-week physical activity program while controlling for baseline values, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted. The pre-test scores were included as covariates to adjust for initial differences between groups. ANCOVA was utilized to perform the analysis, and the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was tested before the analysis. When ANCOVA indicated significant effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni adjustment. Additionally, effect sizes were reported using partial eta squared (η²), interpreted as small (η²≥0.01), medium (η²≥0.06), and large (η²≥0.14) [25]. Percentage changes (%Δ) between pre- and post-intervention measurements were also calculated. The significance level was set at α<0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. A comparison of baseline characteristics between the overweight and normal-weight groups revealed no significant differences for most variables, including height (P=0.457), active jump height (P=0.112), Illinois agility test performance (P=0.189), and sit-and-reach flexibility (P=0.231). However, as expected, significant differences were observed in body mass (P<0.001) and BMI (P<0.001), reflecting the classification criteria for the two groups.

There was a statistically significant difference between the groups in height, BMI, active jump height, Illinois agility test, sit-and-reach flexibility test, flamingo balance test, as well as the times for the S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m tests before and after the program.

The overweight group showed a significant reduction in body mass (F=7.14, P=0.009, %Δ=4.38%) and BMI (F=9.85, P< 0.001, %Δ=3.3%), while the normal group had a smaller but still notable decrease in both measures. Active jump height improved significantly in both groups (F=6.91, P=0.011), with the overweight group showing a %Δ of 7.11% and the normal group improving by 3.89%. The Illinois test demonstrated significant improvements for both groups (F=5.47, P= 0.024), with the overweight group showing a %Δ of 5.29% and the normal group a %Δ of 3.67%. Flexibility, as measured by the sit-and-reach test, increased notably in the overweight group (F=6.81, P=0.013, %Δ=16.61%) and slightly in the normal group (%Δ=10.37%). Balance, assessed using the Flamingo test, improved significantly in the overweight group (F=4.63, P=0.038, %Δ=20.69%) and to a lesser extent in the normal group (%Δ=12.79%). Sprint performance across all distances (5m, 10m, 20m, and 30m) improved significantly in the overweight group (P<0.05 for all), with %Δ ranging from 2.98% to 8.32%, whereas the normal group also improved but with smaller percentage changes (1.17% to 3.11%).

The effect sizes (Partial η²) indicated that BMI (0.155), body mass (0.117), and sprint performances (0.112-0.126) had moderate to large effects, suggesting that the intervention had a significant impact on weight reduction, flexibility, balance, and sprint speed, particularly in overweight individuals (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of a 12-week physical activity program on children aged 8-10. The program incorporated dynamic warm-ups, balance and coordination exercises, perception and reaction drills, multi-limb movement sequences, and interactive games. Each week, it included a variety of motor skill exercises, low-intensity activities, and anaerobic-based training. The study focused on assessing changes in anthropometric characteristics, such as BW, height, and BMI, as well as performance metrics, including active jump height, agility, flexibility, balance, and sprint times for S5m, S10m, S20m, and S30m.

One of the most notable outcomes of the study is the significant reduction in body mass and BMI, particularly in the overweight group. Although the normal-weight group also experienced reductions, the effects were more pronounced in the overweight group, indicating that the program was especially beneficial for weight management among children with higher initial BMI values. These findings align with previous studies suggesting that structured exercise interventions contribute to effective weight control and improved body composition in children [26]. The mechanism underlying this effect likely involves increased energy expenditure and improved metabolic efficiency due to structured exercise [27]. Higher initial BMI values may make individuals more responsive to such interventions, as excess adiposity provides a greater capacity for energy utilization [28]. Additionally, structured exercise programs can enhance muscle mass, improve insulin sensitivity, and regulate appetite, all of which contribute to more effective weight management [29]. Overweight children demonstrated greater improvements in motor skills and body composition compared to normal-weight children. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that individuals with higher initial BMI values tend to respond more favorably to structured exercise interventions due to their greater capacity for energy utilization and relative strength adaptations [28]. Moreover, the significant improvements observed in the overweight group align with findings from Ratajczak et al. [26], who reported that a 12-week combined strength and endurance training program led to notable enhancements in insulin sensitivity and reductions in body fat among overweight women. These metabolic adaptations likely contributed to the greater improvements in motor skills and physical fitness observed in our study.

The improvements in active jump height further demonstrate the program’s effectiveness in enhancing lower-body power. The overweight group showed a greater percentage increase compared to the normal-weight group, suggesting that even children with excess weight can significantly improve their muscular power with consistent physical activity. This result supports previous literature indicating that plyometric and strength-based activities incorporated into physical programs can lead to significant gains in lower-limb explosiveness [30]. The mechanism behind these improvements likely involves neuromuscular adaptations and enhanced muscle activation due to consistent training [31]. Additionally, Adamczak et al. [29] found that physical activity interventions in obese patients resulted in better perinatal outcomes, suggesting that structured exercise programs can effectively address weight management and improve overall health metrics. This supports our conclusion that tailored physical activity programs have substantial potential to address childhood obesity and enhance physical fitness, particularly in overweight populations.

Plyometric and strength-based exercises stimulate fast-twitch muscle fibers, improve motor unit recruitment, and enhance the stretch-shortening cycle efficiency, all of which contribute to greater lower-body power [32]. Additionally, the overweight group’s higher initial mass may have led to greater relative strength adaptations as their muscles adapted to repeated loading, resulting in a more pronounced improvement in jump height [33].

Agility, as measured by the Illinois agility test, also showed marked enhancements in both groups, with the overweight group improving by 5.29% and the normal group by 3.67%. This indicates that participation in structured movement-based activities can enhance quickness and coordination regardless of initial body composition. These improvements likely result from neuromuscular adaptations and increased muscle activation through consistent training [34]. Repeated exposure to dynamic drills, directional changes, and acceleration-deceleration movements strengthens motor pathways, optimizes proprioception, and increases muscle responsiveness [35]. The greater percentage improvement in the overweight group may be attributed to their initial lower baseline performance, allowing for more noticeable gains as their movement mechanics and coordination adapt to training stimuli [36]. Flexibility, assessed through the sit-and-reach test, showed the highest percentage improvement among all measured parameters. These findings suggest that flexibility training incorporated within the program effectively increased the range of motion, which is essential for injury prevention and overall functional movement [37]. The greater relative improvement in the overweight group suggests that balance exercises can have a considerable impact on postural control and coordination, particularly for children with higher body mass [38]. The mechanism behind the greater relative improvement in the overweight group likely involves the adaptation of the body’s postural control systems to the demands of balance exercises [39]. Children with higher body mass may face greater challenges in maintaining stability, which requires greater activation of core and lower-body muscles [40]. Over time, balance exercises can improve proprioception, strengthen stabilizing muscles, and enhance neural control of posture [41]. This leads to more efficient coordination and better overall postural control, with children in the overweight group experiencing more noticeable gains as their bodies adapt to the increased demands [41].

Sprint performance at all distances (5m, 10m, 20m, and 30m) significantly improved in both groups. The improvements in sprint performance can be attributed to enhanced muscle strength, coordination, and neuromuscular efficiency developed through the training program. The training program likely enhanced muscle strength, particularly in the lower body, improving power output during acceleration [42]. Research shows that psychosocial factors, including perceived competence and enjoyment, can significantly influence adherence to physical activity and subsequent performance improvements [27]. In the context of this study, the interactive games and group-based activities incorporated into the program likely fostered a sense of enjoyment and social connection, which may have contributed to the observed improvements. This is particularly relevant for overweight children, who often face stigma and reduced self-esteem [2]. By creating an engaging and supportive environment, the intervention may have boosted participants’ intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, further enhancing their physical and motor skill development.

The limitations of the study should be acknowledged: 1) The lack of long-term follow-up to assess sustained effects; 2) A small sample size (n=40), which may limit generalizability; 3) The use of iPhone-based motion analysis, which may have lower precision compared to gold-standard systems; 4) The focus solely on male participants; and 5) Potential self-selection bias among volunteers.

Conclusions

The physical activity program effectively improved both anthropometric measures (such as body mass and BMI) and motor skills (such as flexibility, balance, agility, and sprint performance) in children. The overweight group showed more significant changes across all measures, highlighting the intervention’s potential for addressing childhood obesity and enhancing overall physical fitness. These findings emphasize the importance of regular physical activity for children’s health and physical development.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code:IR.ARUMS.REC.1397.136) and adhered to the ethical guidelines of the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: AmirAli Jafarnezhadgero and Anders Stålman; Methodology, investigation, data collection and writing the original draft: Ebrahim Piri; Data analysis: Ebrahim Piri and AmirAli Jafarnezhadgero; Review & editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants who volunteered for this study.

References

- Soares R, Brasil I, Monteiro W, Farinatti P. Effects of physical activity on body mass and composition of school-age children and adolescents with overweight or obesity: Systematic review focusing on intervention characteristics. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2023; 33:154-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbmt.2022.09.004] [PMID]

- Bixby H, Mishra A, Martinez AR. Worldwide levels and trends in childhood obesity. In: Moreno LA, editor. Childhood obesity: From basic knowledge to effective prevention. Massachusetts: Academic Press; 2025. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-443-21975-7.00002-2]

- Stults-Kolehmainen MA. Humans have a basic physical and psychological need to move the body: Physical activity as a primary drive. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023; 14:1134049. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1134049] [PMID]

- Dumith SC, Gigante DP, Domingues MR, Kohl HW 3rd.Physical activity change during adolescence: A systematic review and a pooled analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2011; 40(3):685-98. [DOI:10.1093/ije/dyq272] [PMID]

- Findlay LC, Garner RE, Kohen DE. Children’s organized physical activity patterns from childhood into adolescence. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2009; 6(6):708-15. [DOI:10.1123/jpah.6.6.708] [PMID]

- Bucksch J, Möckel J, Kaman A, Sudeck G; HBSC Study Group Germany. Physical activity of older children and adolescents in Germany-Results of the HBSC study 2022 and trends since 2009/10. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2024; 9(1):62-78. [PMID]

- Redublado HJ, Velez L, Serano A, Kilag OK. Enhancing physical activity and movement skills in youth: A systematic review of school-based interventions. International Multidisciplinary Journal of Research for Innovation, Sustainability, and Excellence (IMJRISE). 2024; 1(3):73-8. [Link]

- Boyle B. Effectiveness of a multi-component skill and movement based intervention on Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS) Proficiency and Sports Specific Skill (SSS) Competency amongst adolescent female athletes [MA thesis]. Cork city: Munster Technological University; 2024. [Link]

- Moon J, Webster CA, Stodden DF, Brian A, Mulvey KL, Beets M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity interventions to increase elementary children’s motor competence: A comprehensive school physical activity program perspective. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):826. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-18145-1] [PMID]

- Folder N, Power E, Rietdijk R, Christensen I, Togher L, Parker D. The effectiveness and characteristics of communication partner training programs for families of people with dementia: A systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2024; 64(4):gnad095. [DOI:10.1093/geront/gnad095] [PMID]

- McGowan AL, Chandler MC, Gerde HK. Infusing Physical Activity into Early Childhood Classrooms: Guidance for Best Practices. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2024; 52(8):2021-38. [DOI:10.1007/s10643-023-01532-5]

- Ziegeldorf A, Schoene D, Fatum A, Brauer K, Wulff H. Associations of family socioeconomic indicators and physical activity of primary school-aged children: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2024; 24(1):2247. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-024-19174-6] [PMID]

- Jafarnezhadgero A, Fatollahi A, Amirzadeh N, Siahkouhian M, Granacher U. Ground reaction forces and muscle activity while walking on sand versus stable ground in individuals with pronated feet compared with healthy controls. Plos One. 2019; 14(9):e0223219. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0223219] [PMID]

- Rolland-Cachera MF, Cole TJ, Sempe M, Tichet J, Rossignol C, Charraud A. Body Mass Index variations: centiles from birth to 87 years. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991; 45(1):13-21. [PMID]

- Mayorga-Vega D, Merino-Marban R, Garrido FJ, Viciana J. Comparison between warm-up and cool-down stretching programs on hamstring extensibility gains in primary schoolchildren. Physical Activity Review. 2014; 2:16-24. [Link]

- Battaglia PW, Schrater PR. Humans trade off viewing time and movement duration to improve visuomotor accuracy in a fast reaching task. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007; 27(26):6984-94. [DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1309-07.2007] [PMID]

- Alvurdu S, Akarçeşme C, Altundağ E, Montalvo S. Concurrent validity and reliability of iVMES portable force plate for measuring vertical jump height. Journal of Physical Education and Sport. 2024; 24(4):1024-31. [DOI:10.7752/jpes.2024.04117]

- Garramona FT, Moreira RS, Korch H, Cruz JE, Teixeira LFM. Enhancing Flexibility through Chinese Auriculotherapy: Investigating the Impact on Sit and Reach Test-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Traditional and Integrative Medicine. 2024; 9(2):121-7. [DOI:10.18502/tim.v9i2.15865]

- Michal L. The acute effect of percusive therapy on postural stability and muscle activation in people with chronic ankle instability and controls [MA thesis]. Prague: Charles University; 2023. [Link]

- Aman R, Ullah R, Parveen N. Improving gross motor and fine motor abilities in young children aged 6-8 with adapted badminton exercises: An experimental evaluation. The SPARK. 2024; 9(1):119-34. [Link]

- Jiang W, Alali AA, Mohamad NI, Baki MH, Ayubi N. A Meta-Analysis of Studies on Fundamental Motor Skills in Children aged 3-12 years. Jurnal Sains Sukan & Pendidikan Jasmani. 2024; 13(1):16-37. [DOI:10.37134/jsspj.vol13.1.3.2024]

- Şendil AM, Canlı U, Sheeha BB, Alkhamees NH, Batrakoulis A, Al-Mhanna SB. The effects of structured coordinative exercise protocol on physical fitness, motor competence and inhibitory control in preschool children. Scientific Reports. 2024; 14(1):28462. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-79811-3] [PMID]

- Bai M, Lin N, Yu JJ, Teng Z, Xu M. The effect of planned active play on the fundamental movement skills of preschool children. Human Movement Science. 2024; 96:103241. [DOI:10.1016/j.humov.2024.103241] [PMID]

- Sortwell A, Ramirez-Campillo R, Murphy A, Newton M, Hine G, Piggott B. Associations Between Fundamental Movement Skills, Muscular Fitness, Self-Perception and Physical Activity in Primary School Students. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2024; 9(4):272. [DOI:10.3390/jfmk9040272] [PMID]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1988. [Link]

- Ratajczak M, Krzywicka M, Szulińska M, Musiałowska D, Kusy K, Karolkiewicz J. Effects of 12-week combined strength and endurance circuit training program on insulin sensitivity and retinol-binding protein 4 in women with insulin-resistance and overweight or mild obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity. 2024; 17:93-106. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S432954] [PMID]

- Nutter S, Eggerichs LA, Nagpal TS, Ramos Salas X, Chin Chea C, Saiful S, et al. Changing the global obesity narrative to recognize and reduce weight stigma: A position statement from the World Obesity Federation. Obesity Reviews. 2024; 25(1):e13642. [DOI:10.1111/obr.13642] [PMID]

- Gaweł E, Hall B, Siatkowski S, Grabowska A, Zwierzchowska A. The combined effects of high-intensity interval exercise training and dietary supplementation on reduction of body fat in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(3):355. [DOI:10.3390/nu16030355] [PMID]

- Adamczak L, Mantaj U, Sibiak R, Gutaj P, Wender-Ozegowska E. Physical activity, gestational weight gain in obese patients with early gestational diabetes and the perinatal outcome-a randomised-controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2024; 24(1):104. [DOI:10.1186/s12884-024-06296-3] [PMID]

- Hill RB. The effects of plyometric exercise on lower extremity force production and reactive strength in adolescent female basketball players. California: California State University; 2020. [DOI:10.15640/jpesm.v8n1a5]

- Markovic G, Mikulic P. Neuro-musculoskeletal and performance adaptations to lower-extremity plyometric training. Sports Medicine. 2010; 40(10):859-95. [DOI:10.2165/11318370-000000000-00000] [PMID]

- Cormier P, Freitas TT, Loturco I, Turner A, Virgile A, Haff GG, et al. Within session exercise sequencing during programming for complex training: Historical perspectives, terminology, and training considerations. Sports Medicine. 2022; 52(10):2371-89. [DOI:10.1007/s40279-022-01715-x] [PMID]

- Markovic S, Mirkov DM, Knezevic OM, Jaric S. Jump training with different loads: Effects on jumping performance and power output. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2013; 113(10):2511-21. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-013-2688-6] [PMID]

- Spiteri T, McIntyre F, Specos C, Myszka S. Cognitive training for agility: The integration between perception and action. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2018; 40(1):39-46. [DOI:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000310]

- Buckthorpe M. Optimising the late-stage rehabilitation and return-to-sport training and testing process after ACL reconstruction. Sports Medicine. 2019; 49(7):1043-58. [DOI:10.1007/s40279-019-01102-z] [PMID]

- Ammar A, Salem A, Simak M, Horst F, Schöllhorn W. Acute effects of motor learning models on technical efficiency in strength-coordination exercises: a comparative analysis of olympic snatch biomechanics in beginners. Biology of Sport. 2025; 42(1):151-61. [DOI:10.5114/biolsport.2025.141662] [PMID]

- Stathokostas L, Little RM, Vandervoort A, Paterson DH. Flexibility training and functional ability in older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Aging Research. 2012; 2012:306818. [DOI:10.1155/2012/306818] [PMID]

- Han A, Fu A, Cobley S, Sanders RH. Effectiveness of exercise intervention on improving fundamental movement skills and motor coordination in overweight/obese children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2018; 21(1):89-102. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.07.001] [PMID]

- Del Porto H, Pechak C, Smith D, Reed-Jones R. Biomechanical effects of obesity on balance. International Journal of Exercise Science. 2012; 5(4):301-20. [DOI:10.70252/ZFZP6856]

- Zarei H, Norasteh AA. Effects of core stability training program on trunk muscle endurance in deaf children: A preliminary study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2021; 28:6-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbmt.2021.07.014] [PMID]

- Hlaing SS, Puntumetakul R, Khine EE, Boucaut R. Effects of core stabilization exercise and strengthening exercise on proprioception, balance, muscle thickness and pain related outcomes in patients with subacute nonspecific low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021; 22(1):998. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-021-04858-6] [PMID]

- Lockie RG, Murphy AJ, Schultz AB, Knight TJ, Janse de Jonge XA. The effects of different speed training protocols on sprint acceleration kinematics and muscle strength and power in field sport athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2012; 26(6):1539-50. [DOI:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318234e8a0] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2025/02/4 | Accepted: 2025/05/31 | Published: 2026/01/1

Received: 2025/02/4 | Accepted: 2025/05/31 | Published: 2026/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |