Thu, Feb 19, 2026

Volume 16, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PTJ 2026, 16(1): 83-94 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mousavi S M, Montazeri A, Esnaaharieh M, Izadi N, Poursadeghiyan M, Salehi Sahlabadi A. Comparison and Agreement between WERA, QEC, and ART Methods in Evaluating Drivers’ Musculoskeletal Disorders Risk. PTJ 2026; 16 (1) :83-94

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-695-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-695-en.html

Seyedeh Morvarid Mousavi1

, Amirhossein Montazeri2

, Amirhossein Montazeri2

, Mehrana Esnaaharieh2

, Mehrana Esnaaharieh2

, Neda Izadi3

, Neda Izadi3

, Mohsen Poursadeghiyan4

, Mohsen Poursadeghiyan4

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Amirhossein Montazeri2

, Amirhossein Montazeri2

, Mehrana Esnaaharieh2

, Mehrana Esnaaharieh2

, Neda Izadi3

, Neda Izadi3

, Mohsen Poursadeghiyan4

, Mohsen Poursadeghiyan4

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

, Ali Salehi Sahlabadi *5

1- Department of Occupational Health Engineering, Faculty of Medical Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Health and Safety Engineering, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Centre, Endocrine Sciences Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Department of Occupational Health Engineering, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

5- Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention Research Center, Health Sciences and Environment Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Health and Safety Engineering, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Centre, Endocrine Sciences Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Department of Occupational Health Engineering, School of Health, Ardabil University of Medical Sciences, Ardabil, Iran.

5- Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention Research Center, Health Sciences and Environment Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Workplace ergonomic risk assessment (WERA), Quick exposure check (QEC), Assessment of repetitive tasks (ART), Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs)

Full-Text [PDF 644 kb]

(537 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1472 Views)

Full-Text: (201 Views)

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are defined as any injury or disorder affecting the muscles, nerves, tendons, ligaments, joints, cartilage, spine, or blood vessels, often accompanied by pain and inflammation. However, poor working conditions can exacerbate these disorders [1]. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are among the most serious and common problems among workers [2]. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), after respiratory diseases, MSDs are the second most prevalent occupational health issue [3]. Poorly designed workplaces that do not adhere to ergonomic principles may lead to accidents or incidents during work. Such accidents can result in physical harm to workers, as well as damage to both human and non-human resources [4]. Studies have shown that MSDs lead to increased employee absenteeism and higher healthcare costs for nations [5]. Driving is a significant occupation in today’s society and plays a vital role in daily life [6]. Drivers are exposed to various occupational hazards, such as job stress, chemical, physical, and ergonomic risk factors, throughout their workday [7]. These risk factors can negatively affect their personal and professional lives [6, 8]. The results of studies have shown that the prevalence of MSDs among drivers has varied from 43.1% to 93%. This percentage shows that most of the drivers suffered from MSDs in their working life [9]. Working in different jobs and activities can cause MSDs in different parts of the human body. For example, the assessment of MSDs using the methods, including rapid upper limb assessment (RULA) and the occupational repetitive actions (OCRA) among manual block printing industry workers showed that these people suffer more from pain in the wrist and back areas [10]. The prevalence of spinal disorders (e.g. back and neck pain) has also been observed among professional drivers, which can lead to illness and early retirement [11]. To maintain a stable driving position, these individuals must keep the muscles of their neck, back, shoulders, and arms in static tension for extended periods. Research has shown that this prolonged static posture leads to localized muscle fatigue accompanied by pain and discomfort [12]. Studies indicate that driving in major cities—largely due to traffic congestion, poor road conditions, substandard vehicle designs, air, and noise pollution—exacerbates these disorders [13]. A study by Mozafari et al. in 2015 estimated the prevalence of WMSDs among truck drivers in Qom Province at 78.6%, with back and neck pain being highly common [14]. Another study conducted in Zanjan on 89 drivers revealed that MSDs are widespread among this population [15]. Such trends can lead to absenteeism, loss of work time, increased costs, and workforce injuries, all of which ultimately reduce productivity [16]. Barzegari Bafghi et al. evaluated the risk of MSDs among drivers using the RULA method, finding a correlation between drivers’ postures and their satisfaction [17]. Many studies have used closed-ended self-administered questionnaires and body maps to gather data. Most questions were based on the nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire (NMQ), which is commonly employed to examine work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in working populations [18]. While these questionnaires are reliable and valid, they primarily focus on the prevalence of MSDs and do not examine the factors influencing these disorders or their risk levels. Factors, such as working for a long time, lack of sleep, and occupational stress of drivers, cause many health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome among them [19-22]. MSDs are one of the disorders that can cause many health problems, among drivers. Therefore, we investigated MSDs as one of the health problems among drivers. MSDs in different work-related areas have led to the use of different MSD assessment tools for each job and work environment. For example, in a study on MSDs among construction workers, the RULA and ovako working analysis system (OWAS) method was used [23].

In this research, specific questionnaires for workplace ergonomic risk assessment (WERA), quick exposure check (QEC), and assessment of repetitive tasks (ART) were used, and data on WMSDs among drivers were collected using a body map. A review of the relevant literature and keyword analyses indicated that ergonomic assessments of drivers using WERA, QEC, and ART have received less attention in recent studies. In addition, in these three methods, attention has been paid to the parts of the body that are more active and used more while driving. Wera’s method also considers other factors that affect the musculoskeletal system during driving, such as vibration and contact stress. In addition, the time of use of the musculoskeletal system, which can be a factor affecting the disorders of this area, is examined in all 3 types of this method. These methods may have been under-recognized due to less focus on this specific occupational group and the challenges of conducting research when assessing MSDs among drivers. This study is novel in its approach by combining WERA, QEC, and ART to evaluate ergonomic risks, offering a comprehensive perspective that has not been explored in previous research. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the agreement between these risk assessment methods and to assess the risk and prevalence of MSDs among this occupational group.

Materials and Methods

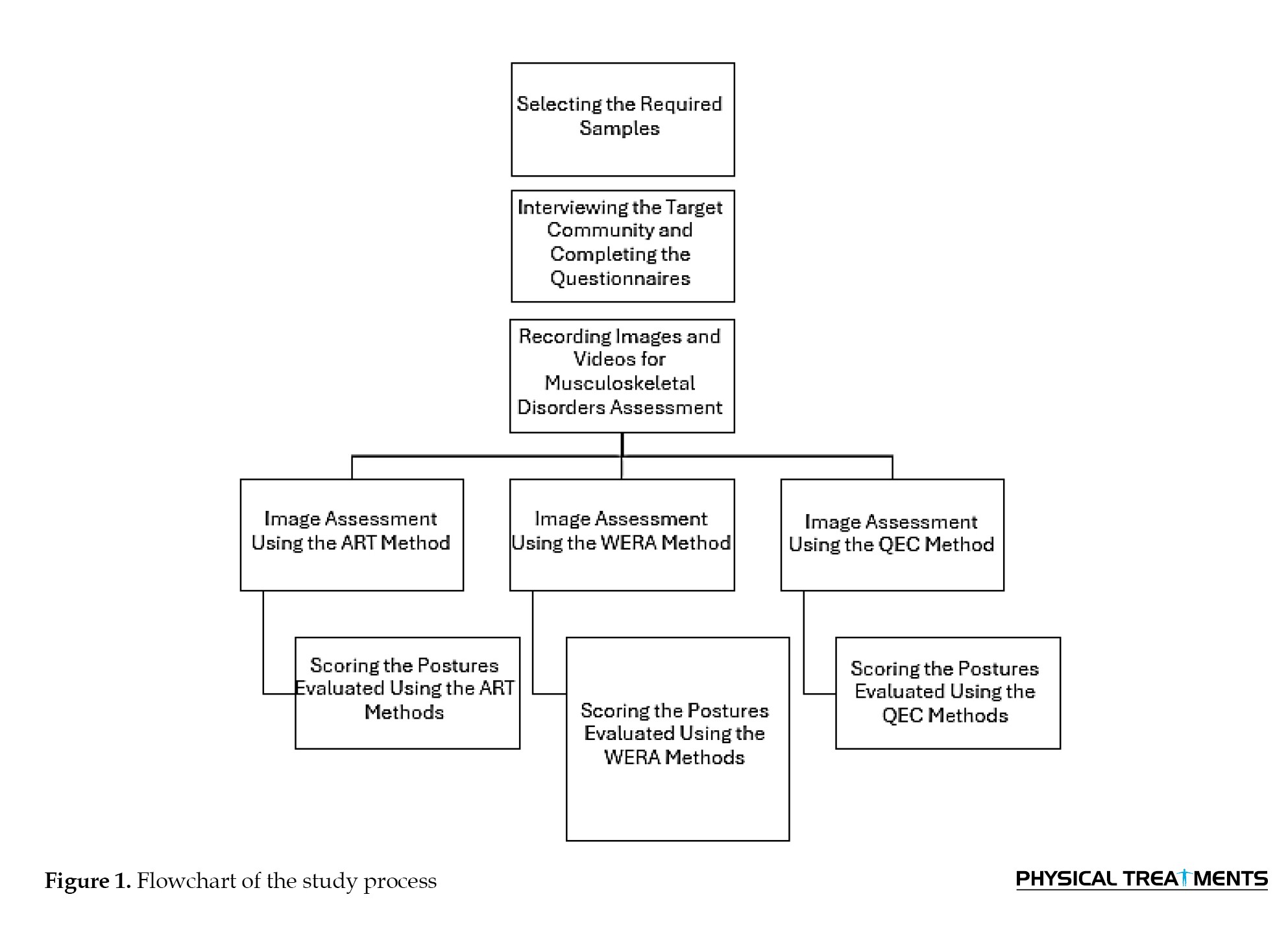

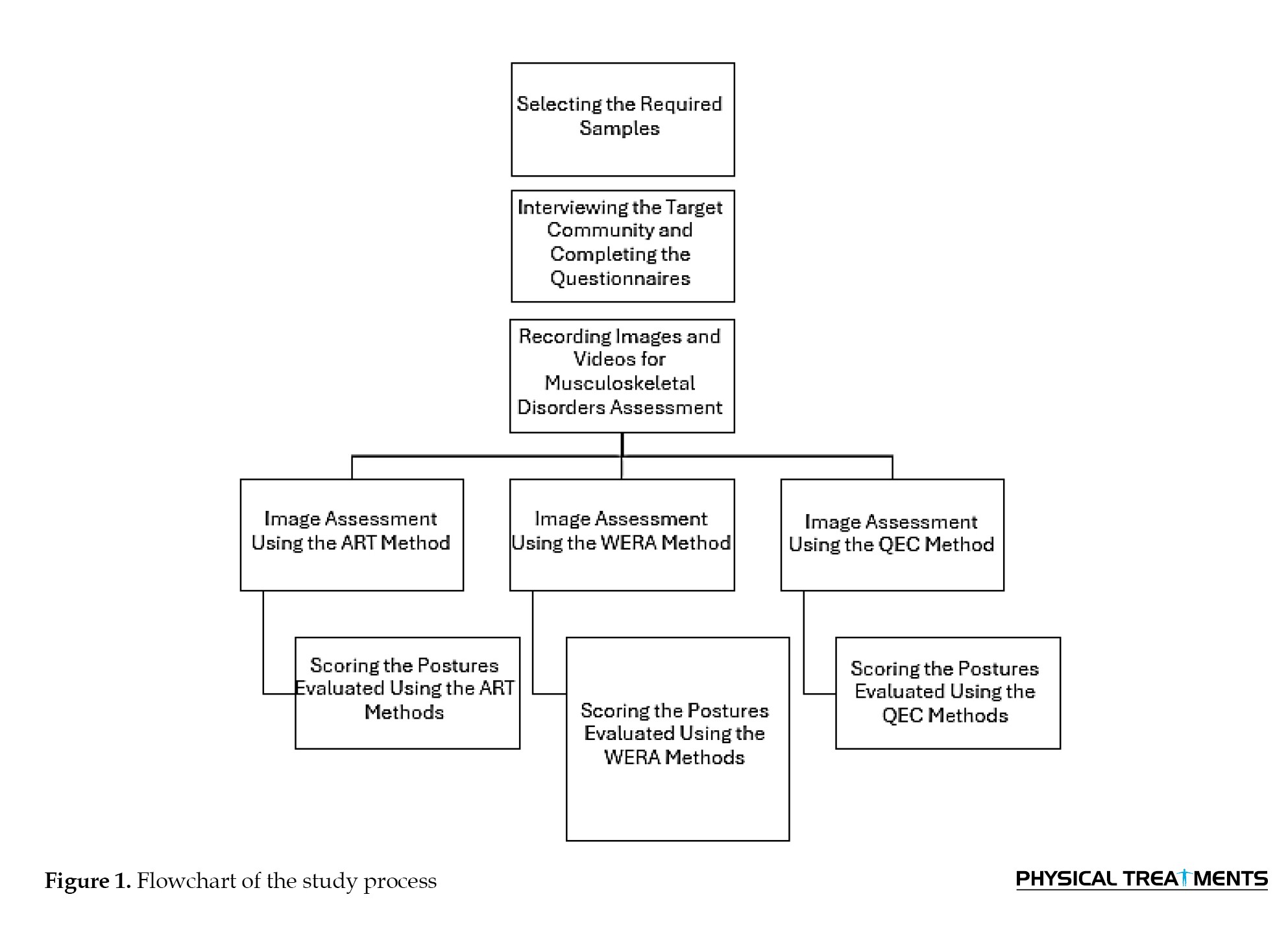

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024, with a sample size of 146 participants determined using the formula for finite populations, based on a study by Motamedzadeh et al. [24]. The inclusion criteria required a minimum of one year of professional driving experience, while the exclusion criteria included a history of musculoskeletal surgery and unwillingness to participate. Experts were present at taxi stations and provided the necessary information about the study by directly interviewing the taxi drivers. They were then asked about their willingness or unwillingness to participate in the study. In the next step, the demographic questionnaire was completed by the participants to verify the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Considering the nature of the job and its associated risk factors, the study employed tools, such as the body map questionnaire to assess the severity of MSDs in the past year, demographic questionnaires to collect personal data (age, work experience, and working hours), and three risk assessment methods: WERA, QEC, and ART. A body map questionnaire was also used to assess the location and intensity of pain, which is critical for evaluating musculoskeletal risk factors [25]. Initially, participants were asked to complete demographic questionnaires for personal data collection and then report their musculoskeletal pain intensity using the Body Map Questionnaire. The postures of the drivers were captured using photography and videography, followed by a risk assessment of their postures using the three risk assessment tools. In the next step, specialists with greater expertise, experience, and mastery of each of the methods reviewed the images and videos and assessed the risk of MSDs using those methods. Six participants who completed the questionnaires expressed unwillingness to continue during posture documentation and were excluded from the study. Details of the study process are illustrated in Figure 1.

Research tools

Body map questionnaire: This questionnaire was utilized to examine the exact location and intensity of participants’ pain. Participants rated pain intensity for different body areas on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1=no pain, 2=mild pain, 3=moderate pain, 4=severe pain, and 5=very severe pain [26]. This self-reported tool focuses on evaluating pain in various body regions [27]. Studies have demonstrated that body map assessments correlate with reported outcomes and have sufficient reliability and validity for use in research [28].

WERA: WERA is an ergonomic risk assessment tool that evaluates six ergonomic risk factors: Awkward postures, contact stress, repetitive work, whole-body vibration, work duration, and applied force. Postures of the shoulder, wrist, back, neck, and legs are independently assessed, as these are closely related to musculoskeletal risk. The final score is categorized into three risk levels: low risk (18–27, acceptable), moderate risk (28–44, requiring further investigation), and high risk (>45, unacceptable risk). Corrective actions are prioritized based on the final score. Studies have shown that WERA has acceptable reliability and validity [2]. Another study indicated that WERA effectively identifies work-related MSDs across a wide range of occupations [29].

QEC: QEC is an observational tool used by occupational health professionals to assess musculoskeletal risk factors. It evaluates four body regions—back, wrist, neck—and includes psychosocial factors [4]. Scores for the back, shoulder, and wrist range from 10–56, with corresponding risk levels: Low (10–20), moderate (21–30), high (31–40), and very high (41–56). For the neck, scores range from 4–18: Low (4–6), moderate (8–10), high (12–14), and very high (16–18). Whole-body exposure scores are expressed as percentages and categorized into four levels: below 40% (acceptable), 41–50% (further investigation required), 51–70% (corrective actions needed soon), and above 70% (unacceptable exposure). Studies indicate that QEC provides reliable assessments of musculoskeletal risk factors [30].

ART: This method is suitable for evaluating repetitive tasks, particularly those involving upper limbs. It assesses postures of the head, neck, back, arms, wrists, and fingers, as well as psychosocial factors that influence the final score. Scores related to force, posture, rest time, and additional activities, combined with the duration of the task, generate the final score. Final scores are categorized as low risk (<11), moderate risk (12–21), and high risk (>22). Studies have validated ART as a suitable tool for evaluating repetitive occupational tasks [31].

Data from 140 taxi drivers were collected by three occupational health experts, all fully trained in the methods used in this study. The experts photographed the drivers in various postures using cameras and completed the questionnaires through direct interviews with participants. At the end of the data collection phase, the experts independently evaluated the photographs and questionnaires. Demographic information, posture assessment scores from the photographs, and questionnaire results were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the MSD risk levels was conducted using SPSS software, version 24. The statistical tests included the t-test to examine the relationship between age and MSDs, as well as the relationship between age and the results of our questionnaires, with a significance level set at P<0.05 for assessment. Results for quantitative variables were reported as Mean±SD, while results for qualitative variables were reported as number (percentage).

Results

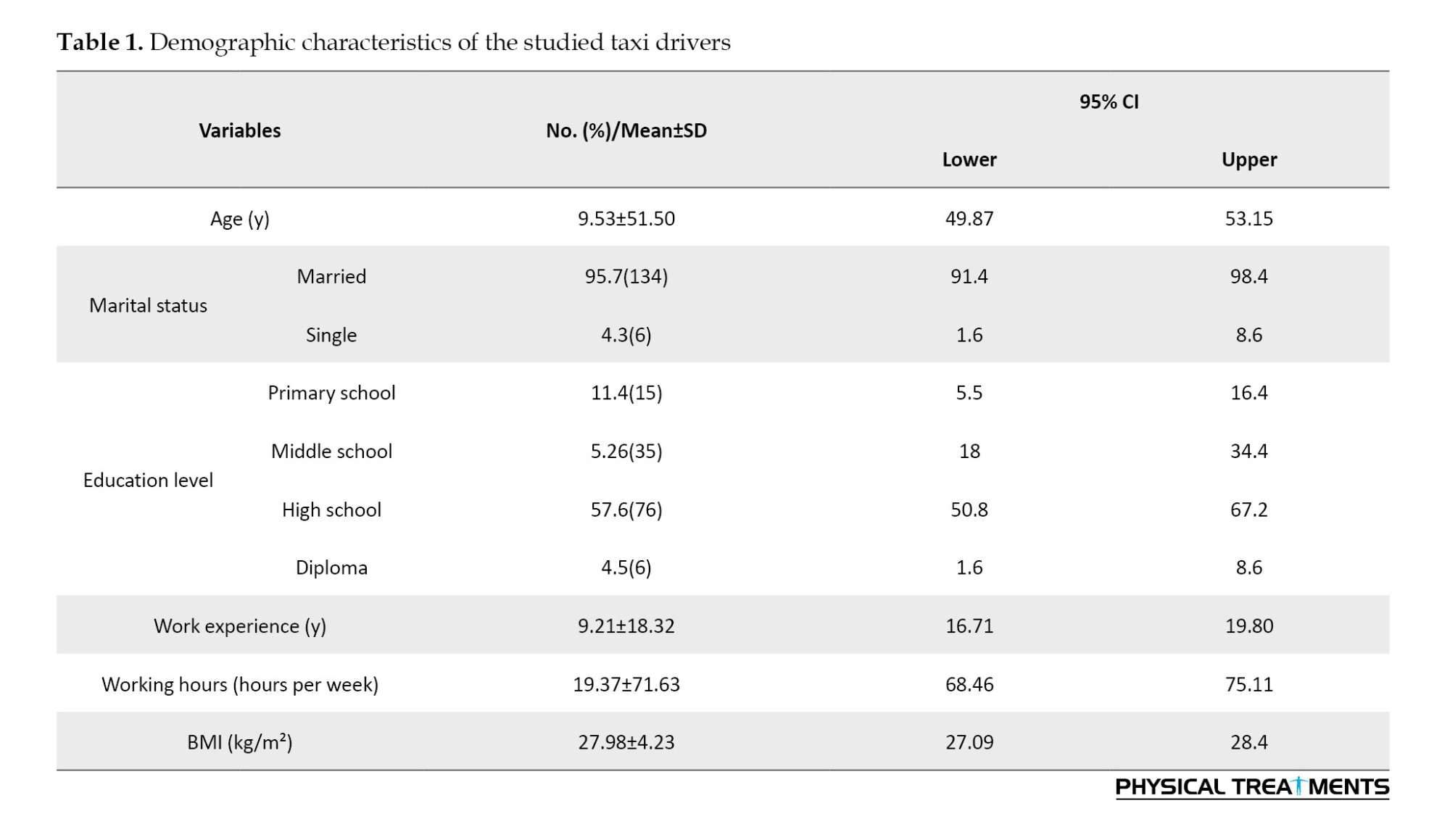

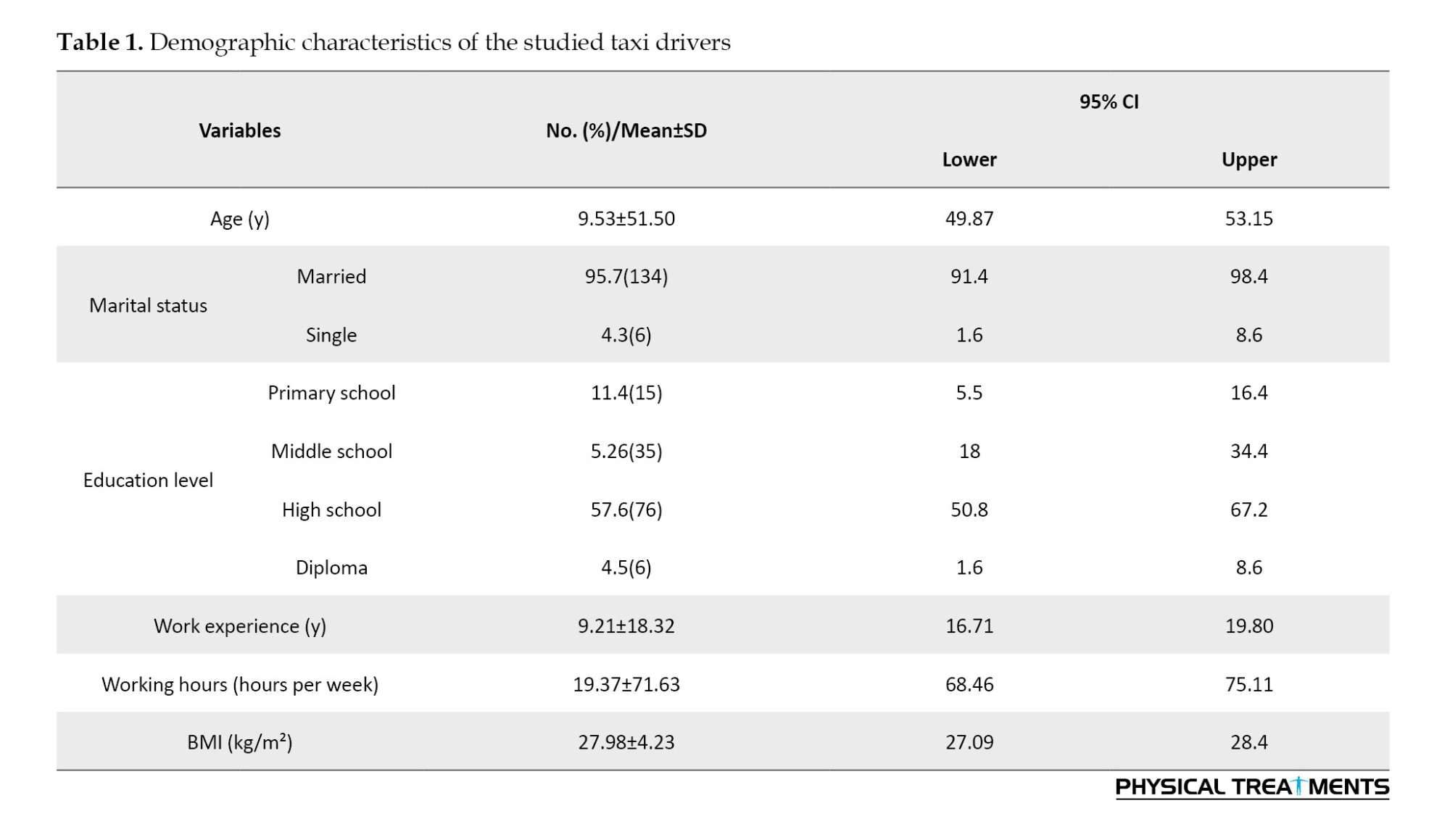

The mean age of the 140 participants in this study was 51.50±9.53 years, and their average work experience was 18.31±9.22 years, with the highest percentage belonging to taxi drivers with over 20 years of work experience. All drivers were male, and none had a history of musculoskeletal surgeries (Table 1).

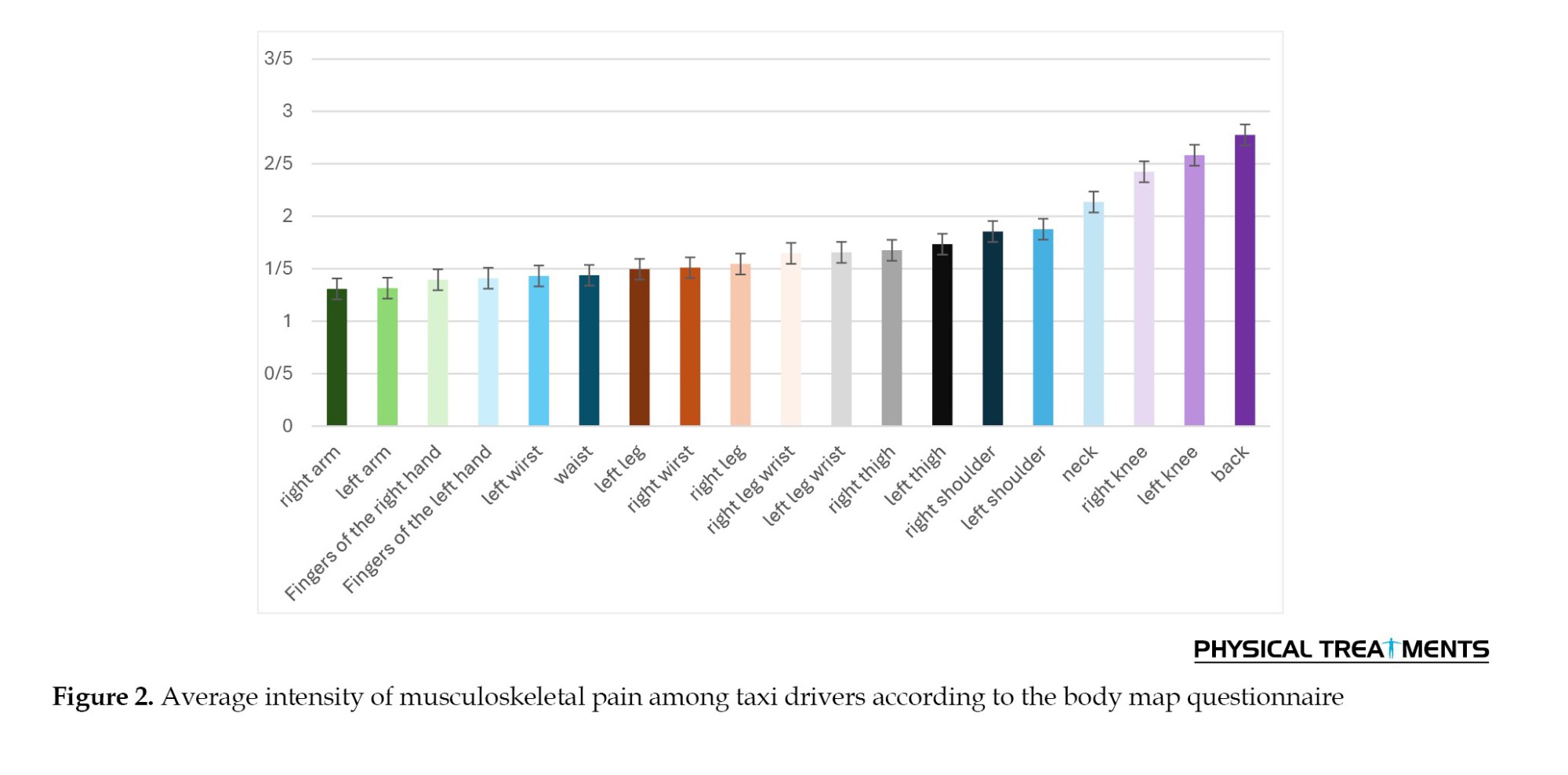

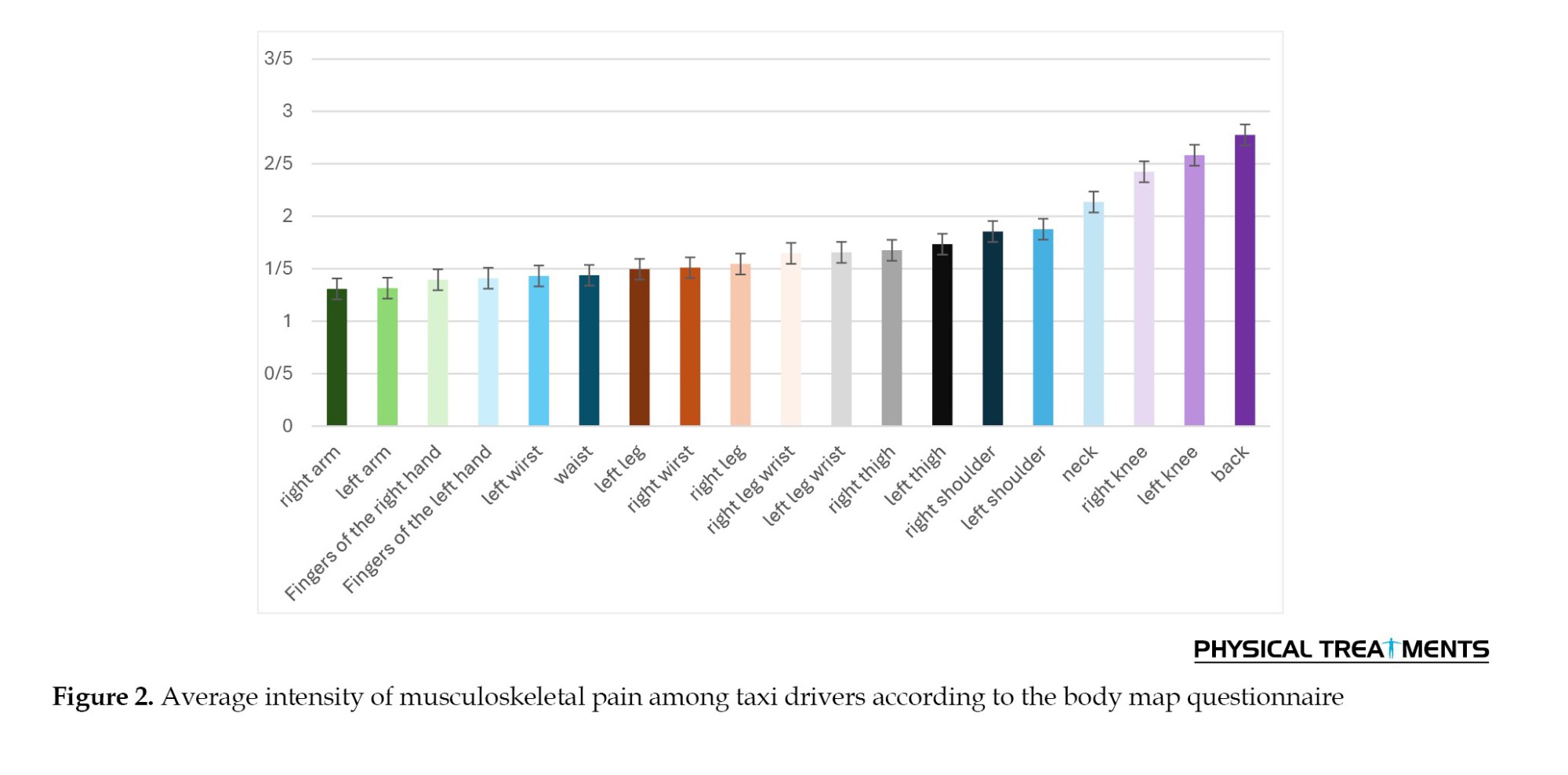

The analysis of MSD severity using the body map questionnaire revealed that lower back pain had the highest prevalence, with a mean score of 2.77±1.64, followed by left knee pain, with a mean score of 2.58±1.45. Participants predominantly reported musculoskeletal discomfort in these regions (Figure 2).

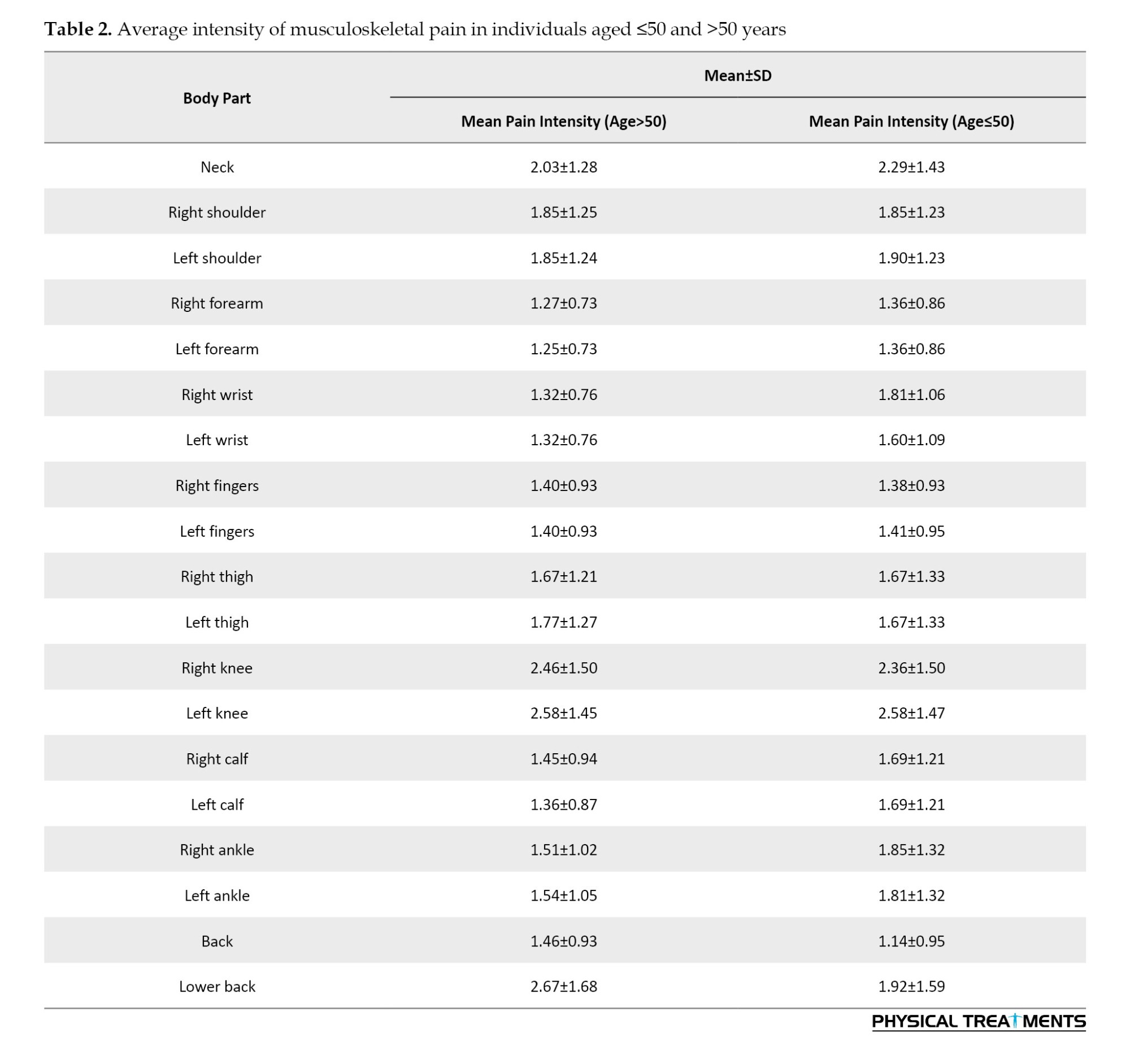

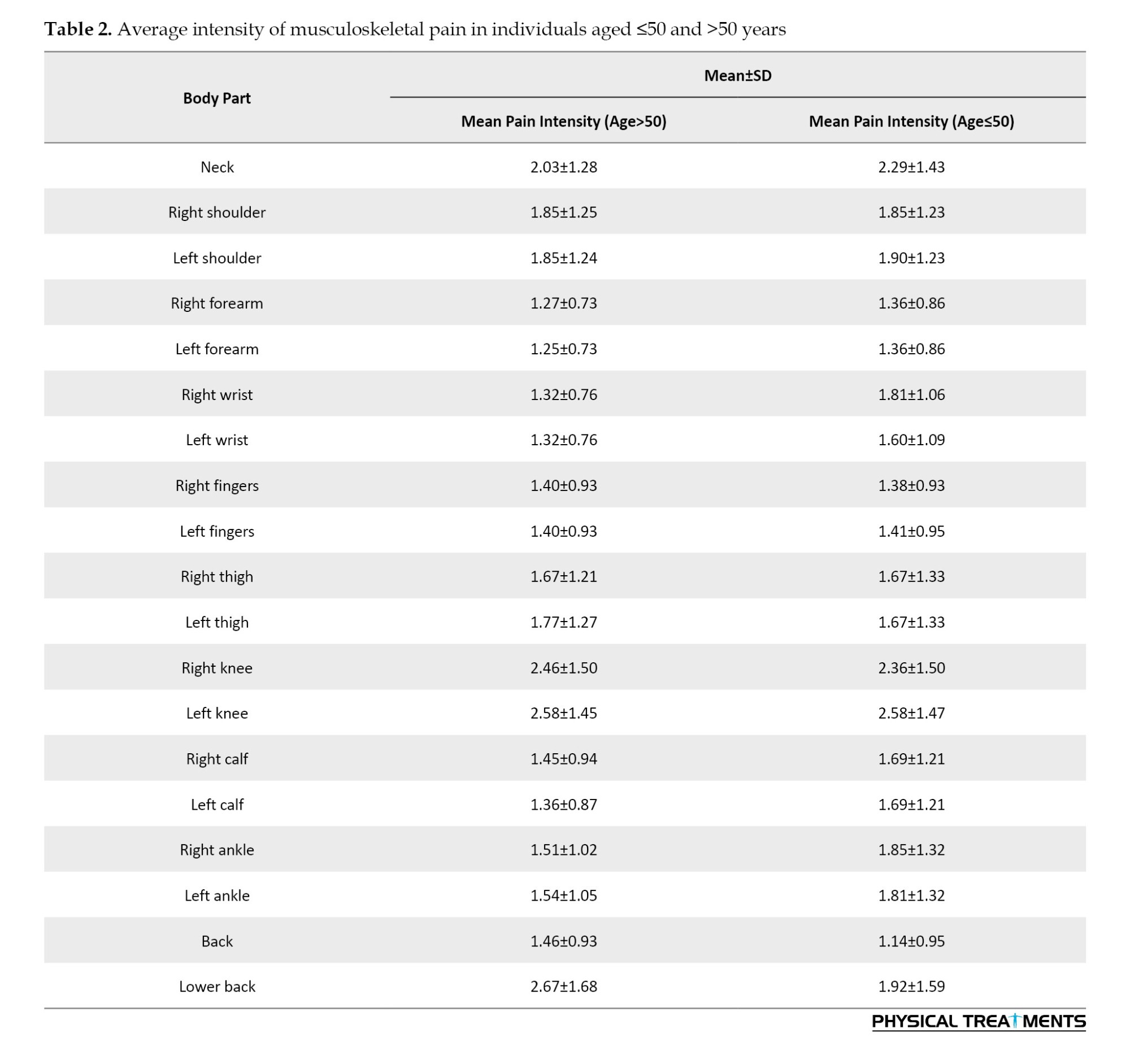

Additionally, the results showed no significant correlation between age and musculoskeletal pain in any body region, as the severity of pain in the knees and lower back was consistent across both groups: Participants aged ≤50 years and those aged >50 years (P>0.05). However, individuals aged ≤50 years reported greater pain severity in the left knee (2.58), right knee (2.36), neck (2.58), and lower back (1.92), while they reported the lowest pain severity in the back (1.14). On the other hand, participants aged >50 years experienced more pronounced pain in the lower back (2.67), left knee (2.58), and right knee (2.46), while they reported less pain in the forearms (1.27) (Table 2).

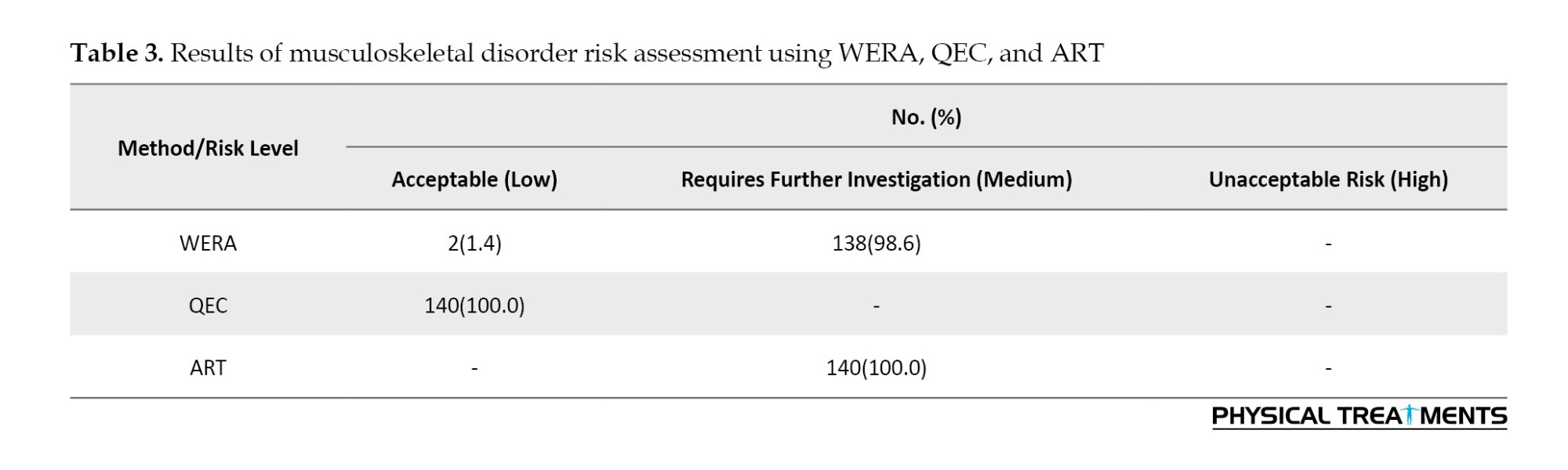

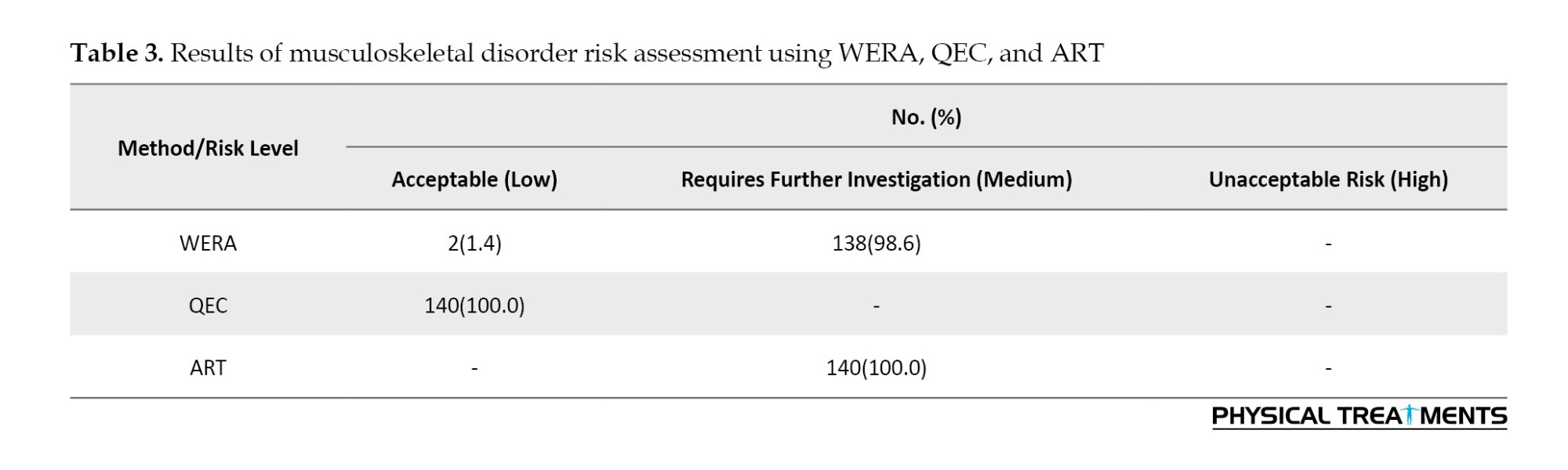

Risk assessments for MSDs using WERA revealed that 98.6% of participants fell into the moderate-risk category, while 1.4% were classified as low-risk. The WERA risk scores ranged between 25 and 35, indicating an overall moderate risk of developing MSDs. Additionally, this method identified the knees as the body region with the highest risk for MSDs among taxi drivers. Conversely, the QEC method classified all participants within the acceptable risk range, as the final risk scores were 40% or lower, signifying a tolerable risk level. The risk percentage for taxi drivers ranged between 30% and 40%. Risk evaluation using ART showed that all participants were in the moderate-risk category, with scores ranging from 13 to 21. In summary, WERA and ART identified participants as being in the moderate-risk category, whereas QEC indicated that participants were in the low and acceptable-risk range (Table 3).

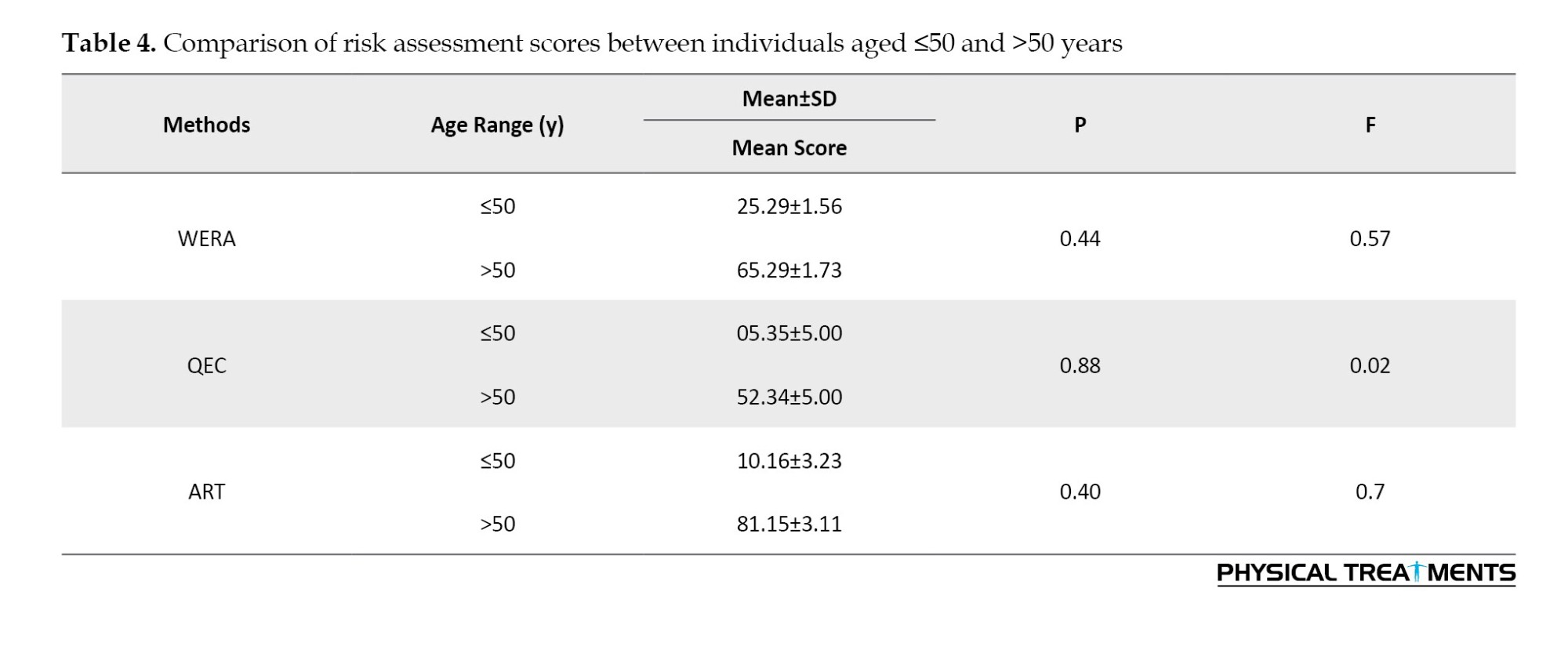

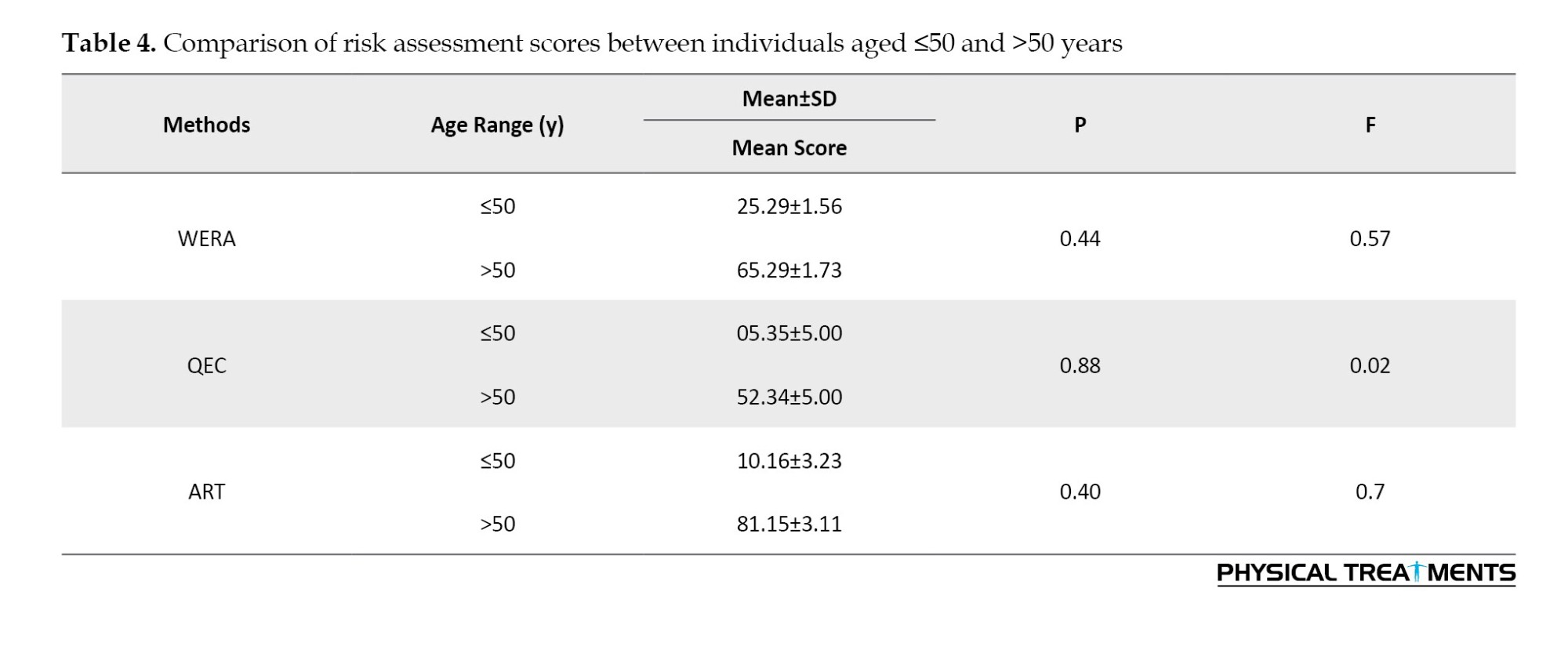

Table 3 shows that both WERA and ART indicated a moderate level of risk in the studied population. In contrast, assessments using the QEC method suggested that the risk of MSDs among drivers fell within the low-risk range. This finding indicates that WERA and ART show a higher level of agreement with each other. According to Table 4, individuals over 50 years old received higher risk scores using WERA and QEC compared to those under 50. On the other hand, the average risk score for individuals over 50 in ART was lower than that of individuals under 50. However, the results of the t-test showed that these differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the risk of MSDs among urban taxi drivers. The risk of MSDs was assessed using three methods: WERA, QEC, and ART, and the level of agreement between these methods was also evaluated. Our results showed that the highest levels of pain and discomfort, according to the Body Map Questionnaire, were reported in the lower back region, with 51% of participants attributing a pain score of 3 or higher to this area. However, the results from the musculoskeletal risk assessments using all three methods indicated that the posture of the participants’ backs was at a low-risk level, as the back was supported, and there was no opportunity for rotation. However, the postures were static, and the prolonged sitting throughout the day led to most of the participants experiencing pain in the lower back.

The results of a study conducted by Moradpour et al. among taxi drivers in Shahrood aligned with our findings. This study, using MFA and CMDQ, showed that the highest levels of fatigue and musculoskeletal discomfort were in the lower back region. Their results, obtained through different methods, further support our findings [32]. A study conducted on 382 taxi drivers using QEC also revealed that the overall score for back posture was low. Therefore, it can be concluded that long hours of sitting and repetitive tasks contribute to musculoskeletal discomfort in the lower back area among taxi drivers.

Furthermore, based on the risk assessment using QEC, vibration from vehicle movement could also be considered a contributing factor to the pain experienced in the back. Although this vibration is minimal, due to the continuous and prolonged exposure of taxi drivers to it, it leads to increased fatigue, stress, and reduced energy levels [33]. A 2024 review that examined 1,606 studies on MSDs among taxi drivers concluded that their highest prevalence among taxi drivers was in the lower back region [34] such as other industrial worker [35]. A study conducted in 23 different countries across 14 types of transportation vehicles showed that the lower back was the most common area affected by musculoskeletal pain. Following that, the neck, back, shoulders, knees, thighs, wrists, feet, and elbows were also at risk for musculoskeletal pain [9]. In the present study, MSDs were most common in the lower back and knees, with less severe pain reported in the shoulder and hand regions. According to the results of this study, the second most affected area among taxi drivers was the left knee. This body part was particularly stressed due to the pressure applied to the clutch, making it the second area that caused discomfort among taxi drivers. The musculoskeletal risk assessment using WERA also showed that the knee scores were high due to prolonged and severe bending, which aligns with the body map questionnaire results, indicating that most participants reported pain and discomfort in their knees.

Another study by Mazloumi et al. clearly demonstrated a significant difference in the perceived discomfort in body areas involved in clutching before and after using the clutch. The highest levels of discomfort were reported in the lower back and knees, which aligns with our findings [36]. Additionally, another study showed that the highest prevalence of occupational MSDs among taxi drivers was in the lower back, while the lowest prevalence was found in the elbow region [37]. These results further confirm the findings of the present study.

Another study that examined drivers of eight different types of vehicles showed that long driving hours, poor posture, long working hours, alcohol consumption, and sitting in uncomfortable positions were factors that contributed to MSDs [38]. Therefore, by examining the physical condition of drivers and assessing the risk level of MSDs in their working postures, it is possible to identify the body parts most at risk. Subsequently, through the implementation of necessary training and management interventions, these disorders can be reduced in the long term. On the other hand, inappropriate seating is one of the factors that not only impacts MSDs but also decreases job satisfaction [39].

In conclusion, prolonged sitting during taxi driving and the pressure exerted when using the clutch lead to significant musculoskeletal pain, particularly in the lower back. Although taxi drivers maintain a proper back posture with support from the chair, the extended periods of sitting eventually result in musculoskeletal discomfort in the lower back. Additionally, the knees remain in a bent position for extended periods during driving, which leads to improper posture. The continuous bending and pressure applied during clutching contribute to additional strain on the knees. It can be suggested that increasing rest periods and reducing working hours for drivers could reduce the pressure on the back and knees. Furthermore, appropriate exercises aimed at strengthening the back and leg muscles can help support the spine and knees.

Our study showed that there was agreement between the methods WERA and ART, as both indicated a moderate risk for MSDs. WERA assesses shoulders, wrists, back, neck, knees, load handling, vibration, and contact stress, while ART focuses more on the upper body, evaluating arms, wrists, fingers, and load handling. Although ART does not assess knees, its results aligned with those of WERA. However, the knees are one of the body parts that are heavily used in driving. Also, our results showed that the average intensity of pain in the drivers’ knees according to the body map questionnaire was the highest after the back. Therefore, in the evaluation of MSDs in drivers, a method that evaluates the legs, especially the knees, should be used. Based on this, although the results of the WERA and ART were close to each other, the former is a more reliable method for the assessment of MSDs in the driver community.

In QEC, posture assessment is limited to the shoulders, wrists, neck, and back. Although factors, such as load handling, vibration, visual demands, and stress, are self-reported by participants in the second questionnaire, this self-reporting has lower reliability compared to evaluations performed by experts. Although QEC can be considered a complete assessment of MSDs, because it examines both physical and psychological factors, the self-report part of this questionnaire can directly affect the final risk assessment [33]. This aspect may be influenced by the individual’s condition, and as a result, the assessment of the risk of MSDs may be misguided.. Therefore, although the QEC method is one of the proposed approaches for evaluating MSDs, as a standalone method, it is not completely accurate or efficient and does not provide a fully reliable report. This assertion was clearly demonstrated in our results, as WERA and ART reported more similar outcomes than QEC.

This study has some limitations that may affect the findings. Due to the limited sample of urban taxi drivers, the results may not be fully representative of all drivers, as weather conditions and traffic vary by region. Weather changes, such as snow and rain, as well as working on busy roads, can prolong routes and lead to increased driving time, which may contribute to a higher incidence of MSDs. Furthermore, because of the busy and impatient nature of the target group, the study only included 140 drivers, which may not be sufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The sample size was small due to limited access to participants. Urban taxi drivers often work long and irregular hours, making it challenging to attract a sufficient number of participants within the given timeframe, resulting in the study being conducted with a minimal sample size.

Conclusion

The results of the assessment using the risk evaluation methods—WERA, ART, QEC—and the Body Map Questionnaire indicated that the highest risk of MSDs occurred in the lower back and knees, with participants reporting greater pain intensity in these areas. Since prolonged sitting and pressure on pedals increase the severity of pain in the lower back and knees, increasing rest periods and reducing working hours can help alleviate these issues. Additionally, while both WERA and ART showed a medium level of risk, QEC indicated a low risk level, leading to the conclusion that WERA and ART are more consistent with each other. Based on the evaluation results and the body areas assessed by each method, it can be inferred that, given the high prevalence of MSDs in the lower back and lower extremities among taxi drivers, a method focusing on these areas is of greater importance. Also, contrary to QEC, WERA lacks a self-reporting section, which can have a negative effect on the main result of assessing the risk of MSDs. Thus, it can be said that WERA is a more acceptable method for examining MSDs in the drivers’ community. Since WERA includes an assessment of legs and knees, its application to evaluate MSDs among drivers can be considered both effective and practical.

Also, since our results showed that MSDs in the knees and back are more common among drivers, it is suggested that drivers keep their knees in a straight position during rest. Also, using standard pillows can support drivers’ backs. It is recommended to avoid uninterrupted driving. Using a rhythm of rest and intermittent work can help reduce musculoskeletal pain in this occupational group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1403.078). All participants were informed about the objectives and procedures of the study, and their consent was obtained through signed informed consent forms. Participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential and would only be used for research purposes.

Funding

This article is the result of a research project and financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted among taxi drivers in Tehran. The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Research Deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Occupational Health Department of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and all participants in this research for their valuable contributions.

References

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are defined as any injury or disorder affecting the muscles, nerves, tendons, ligaments, joints, cartilage, spine, or blood vessels, often accompanied by pain and inflammation. However, poor working conditions can exacerbate these disorders [1]. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are among the most serious and common problems among workers [2]. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), after respiratory diseases, MSDs are the second most prevalent occupational health issue [3]. Poorly designed workplaces that do not adhere to ergonomic principles may lead to accidents or incidents during work. Such accidents can result in physical harm to workers, as well as damage to both human and non-human resources [4]. Studies have shown that MSDs lead to increased employee absenteeism and higher healthcare costs for nations [5]. Driving is a significant occupation in today’s society and plays a vital role in daily life [6]. Drivers are exposed to various occupational hazards, such as job stress, chemical, physical, and ergonomic risk factors, throughout their workday [7]. These risk factors can negatively affect their personal and professional lives [6, 8]. The results of studies have shown that the prevalence of MSDs among drivers has varied from 43.1% to 93%. This percentage shows that most of the drivers suffered from MSDs in their working life [9]. Working in different jobs and activities can cause MSDs in different parts of the human body. For example, the assessment of MSDs using the methods, including rapid upper limb assessment (RULA) and the occupational repetitive actions (OCRA) among manual block printing industry workers showed that these people suffer more from pain in the wrist and back areas [10]. The prevalence of spinal disorders (e.g. back and neck pain) has also been observed among professional drivers, which can lead to illness and early retirement [11]. To maintain a stable driving position, these individuals must keep the muscles of their neck, back, shoulders, and arms in static tension for extended periods. Research has shown that this prolonged static posture leads to localized muscle fatigue accompanied by pain and discomfort [12]. Studies indicate that driving in major cities—largely due to traffic congestion, poor road conditions, substandard vehicle designs, air, and noise pollution—exacerbates these disorders [13]. A study by Mozafari et al. in 2015 estimated the prevalence of WMSDs among truck drivers in Qom Province at 78.6%, with back and neck pain being highly common [14]. Another study conducted in Zanjan on 89 drivers revealed that MSDs are widespread among this population [15]. Such trends can lead to absenteeism, loss of work time, increased costs, and workforce injuries, all of which ultimately reduce productivity [16]. Barzegari Bafghi et al. evaluated the risk of MSDs among drivers using the RULA method, finding a correlation between drivers’ postures and their satisfaction [17]. Many studies have used closed-ended self-administered questionnaires and body maps to gather data. Most questions were based on the nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire (NMQ), which is commonly employed to examine work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in working populations [18]. While these questionnaires are reliable and valid, they primarily focus on the prevalence of MSDs and do not examine the factors influencing these disorders or their risk levels. Factors, such as working for a long time, lack of sleep, and occupational stress of drivers, cause many health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome among them [19-22]. MSDs are one of the disorders that can cause many health problems, among drivers. Therefore, we investigated MSDs as one of the health problems among drivers. MSDs in different work-related areas have led to the use of different MSD assessment tools for each job and work environment. For example, in a study on MSDs among construction workers, the RULA and ovako working analysis system (OWAS) method was used [23].

In this research, specific questionnaires for workplace ergonomic risk assessment (WERA), quick exposure check (QEC), and assessment of repetitive tasks (ART) were used, and data on WMSDs among drivers were collected using a body map. A review of the relevant literature and keyword analyses indicated that ergonomic assessments of drivers using WERA, QEC, and ART have received less attention in recent studies. In addition, in these three methods, attention has been paid to the parts of the body that are more active and used more while driving. Wera’s method also considers other factors that affect the musculoskeletal system during driving, such as vibration and contact stress. In addition, the time of use of the musculoskeletal system, which can be a factor affecting the disorders of this area, is examined in all 3 types of this method. These methods may have been under-recognized due to less focus on this specific occupational group and the challenges of conducting research when assessing MSDs among drivers. This study is novel in its approach by combining WERA, QEC, and ART to evaluate ergonomic risks, offering a comprehensive perspective that has not been explored in previous research. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the agreement between these risk assessment methods and to assess the risk and prevalence of MSDs among this occupational group.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024, with a sample size of 146 participants determined using the formula for finite populations, based on a study by Motamedzadeh et al. [24]. The inclusion criteria required a minimum of one year of professional driving experience, while the exclusion criteria included a history of musculoskeletal surgery and unwillingness to participate. Experts were present at taxi stations and provided the necessary information about the study by directly interviewing the taxi drivers. They were then asked about their willingness or unwillingness to participate in the study. In the next step, the demographic questionnaire was completed by the participants to verify the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Considering the nature of the job and its associated risk factors, the study employed tools, such as the body map questionnaire to assess the severity of MSDs in the past year, demographic questionnaires to collect personal data (age, work experience, and working hours), and three risk assessment methods: WERA, QEC, and ART. A body map questionnaire was also used to assess the location and intensity of pain, which is critical for evaluating musculoskeletal risk factors [25]. Initially, participants were asked to complete demographic questionnaires for personal data collection and then report their musculoskeletal pain intensity using the Body Map Questionnaire. The postures of the drivers were captured using photography and videography, followed by a risk assessment of their postures using the three risk assessment tools. In the next step, specialists with greater expertise, experience, and mastery of each of the methods reviewed the images and videos and assessed the risk of MSDs using those methods. Six participants who completed the questionnaires expressed unwillingness to continue during posture documentation and were excluded from the study. Details of the study process are illustrated in Figure 1.

Research tools

Body map questionnaire: This questionnaire was utilized to examine the exact location and intensity of participants’ pain. Participants rated pain intensity for different body areas on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1=no pain, 2=mild pain, 3=moderate pain, 4=severe pain, and 5=very severe pain [26]. This self-reported tool focuses on evaluating pain in various body regions [27]. Studies have demonstrated that body map assessments correlate with reported outcomes and have sufficient reliability and validity for use in research [28].

WERA: WERA is an ergonomic risk assessment tool that evaluates six ergonomic risk factors: Awkward postures, contact stress, repetitive work, whole-body vibration, work duration, and applied force. Postures of the shoulder, wrist, back, neck, and legs are independently assessed, as these are closely related to musculoskeletal risk. The final score is categorized into three risk levels: low risk (18–27, acceptable), moderate risk (28–44, requiring further investigation), and high risk (>45, unacceptable risk). Corrective actions are prioritized based on the final score. Studies have shown that WERA has acceptable reliability and validity [2]. Another study indicated that WERA effectively identifies work-related MSDs across a wide range of occupations [29].

QEC: QEC is an observational tool used by occupational health professionals to assess musculoskeletal risk factors. It evaluates four body regions—back, wrist, neck—and includes psychosocial factors [4]. Scores for the back, shoulder, and wrist range from 10–56, with corresponding risk levels: Low (10–20), moderate (21–30), high (31–40), and very high (41–56). For the neck, scores range from 4–18: Low (4–6), moderate (8–10), high (12–14), and very high (16–18). Whole-body exposure scores are expressed as percentages and categorized into four levels: below 40% (acceptable), 41–50% (further investigation required), 51–70% (corrective actions needed soon), and above 70% (unacceptable exposure). Studies indicate that QEC provides reliable assessments of musculoskeletal risk factors [30].

ART: This method is suitable for evaluating repetitive tasks, particularly those involving upper limbs. It assesses postures of the head, neck, back, arms, wrists, and fingers, as well as psychosocial factors that influence the final score. Scores related to force, posture, rest time, and additional activities, combined with the duration of the task, generate the final score. Final scores are categorized as low risk (<11), moderate risk (12–21), and high risk (>22). Studies have validated ART as a suitable tool for evaluating repetitive occupational tasks [31].

Data from 140 taxi drivers were collected by three occupational health experts, all fully trained in the methods used in this study. The experts photographed the drivers in various postures using cameras and completed the questionnaires through direct interviews with participants. At the end of the data collection phase, the experts independently evaluated the photographs and questionnaires. Demographic information, posture assessment scores from the photographs, and questionnaire results were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the MSD risk levels was conducted using SPSS software, version 24. The statistical tests included the t-test to examine the relationship between age and MSDs, as well as the relationship between age and the results of our questionnaires, with a significance level set at P<0.05 for assessment. Results for quantitative variables were reported as Mean±SD, while results for qualitative variables were reported as number (percentage).

Results

The mean age of the 140 participants in this study was 51.50±9.53 years, and their average work experience was 18.31±9.22 years, with the highest percentage belonging to taxi drivers with over 20 years of work experience. All drivers were male, and none had a history of musculoskeletal surgeries (Table 1).

The analysis of MSD severity using the body map questionnaire revealed that lower back pain had the highest prevalence, with a mean score of 2.77±1.64, followed by left knee pain, with a mean score of 2.58±1.45. Participants predominantly reported musculoskeletal discomfort in these regions (Figure 2).

Additionally, the results showed no significant correlation between age and musculoskeletal pain in any body region, as the severity of pain in the knees and lower back was consistent across both groups: Participants aged ≤50 years and those aged >50 years (P>0.05). However, individuals aged ≤50 years reported greater pain severity in the left knee (2.58), right knee (2.36), neck (2.58), and lower back (1.92), while they reported the lowest pain severity in the back (1.14). On the other hand, participants aged >50 years experienced more pronounced pain in the lower back (2.67), left knee (2.58), and right knee (2.46), while they reported less pain in the forearms (1.27) (Table 2).

Risk assessments for MSDs using WERA revealed that 98.6% of participants fell into the moderate-risk category, while 1.4% were classified as low-risk. The WERA risk scores ranged between 25 and 35, indicating an overall moderate risk of developing MSDs. Additionally, this method identified the knees as the body region with the highest risk for MSDs among taxi drivers. Conversely, the QEC method classified all participants within the acceptable risk range, as the final risk scores were 40% or lower, signifying a tolerable risk level. The risk percentage for taxi drivers ranged between 30% and 40%. Risk evaluation using ART showed that all participants were in the moderate-risk category, with scores ranging from 13 to 21. In summary, WERA and ART identified participants as being in the moderate-risk category, whereas QEC indicated that participants were in the low and acceptable-risk range (Table 3).

Table 3 shows that both WERA and ART indicated a moderate level of risk in the studied population. In contrast, assessments using the QEC method suggested that the risk of MSDs among drivers fell within the low-risk range. This finding indicates that WERA and ART show a higher level of agreement with each other. According to Table 4, individuals over 50 years old received higher risk scores using WERA and QEC compared to those under 50. On the other hand, the average risk score for individuals over 50 in ART was lower than that of individuals under 50. However, the results of the t-test showed that these differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the risk of MSDs among urban taxi drivers. The risk of MSDs was assessed using three methods: WERA, QEC, and ART, and the level of agreement between these methods was also evaluated. Our results showed that the highest levels of pain and discomfort, according to the Body Map Questionnaire, were reported in the lower back region, with 51% of participants attributing a pain score of 3 or higher to this area. However, the results from the musculoskeletal risk assessments using all three methods indicated that the posture of the participants’ backs was at a low-risk level, as the back was supported, and there was no opportunity for rotation. However, the postures were static, and the prolonged sitting throughout the day led to most of the participants experiencing pain in the lower back.

The results of a study conducted by Moradpour et al. among taxi drivers in Shahrood aligned with our findings. This study, using MFA and CMDQ, showed that the highest levels of fatigue and musculoskeletal discomfort were in the lower back region. Their results, obtained through different methods, further support our findings [32]. A study conducted on 382 taxi drivers using QEC also revealed that the overall score for back posture was low. Therefore, it can be concluded that long hours of sitting and repetitive tasks contribute to musculoskeletal discomfort in the lower back area among taxi drivers.

Furthermore, based on the risk assessment using QEC, vibration from vehicle movement could also be considered a contributing factor to the pain experienced in the back. Although this vibration is minimal, due to the continuous and prolonged exposure of taxi drivers to it, it leads to increased fatigue, stress, and reduced energy levels [33]. A 2024 review that examined 1,606 studies on MSDs among taxi drivers concluded that their highest prevalence among taxi drivers was in the lower back region [34] such as other industrial worker [35]. A study conducted in 23 different countries across 14 types of transportation vehicles showed that the lower back was the most common area affected by musculoskeletal pain. Following that, the neck, back, shoulders, knees, thighs, wrists, feet, and elbows were also at risk for musculoskeletal pain [9]. In the present study, MSDs were most common in the lower back and knees, with less severe pain reported in the shoulder and hand regions. According to the results of this study, the second most affected area among taxi drivers was the left knee. This body part was particularly stressed due to the pressure applied to the clutch, making it the second area that caused discomfort among taxi drivers. The musculoskeletal risk assessment using WERA also showed that the knee scores were high due to prolonged and severe bending, which aligns with the body map questionnaire results, indicating that most participants reported pain and discomfort in their knees.

Another study by Mazloumi et al. clearly demonstrated a significant difference in the perceived discomfort in body areas involved in clutching before and after using the clutch. The highest levels of discomfort were reported in the lower back and knees, which aligns with our findings [36]. Additionally, another study showed that the highest prevalence of occupational MSDs among taxi drivers was in the lower back, while the lowest prevalence was found in the elbow region [37]. These results further confirm the findings of the present study.

Another study that examined drivers of eight different types of vehicles showed that long driving hours, poor posture, long working hours, alcohol consumption, and sitting in uncomfortable positions were factors that contributed to MSDs [38]. Therefore, by examining the physical condition of drivers and assessing the risk level of MSDs in their working postures, it is possible to identify the body parts most at risk. Subsequently, through the implementation of necessary training and management interventions, these disorders can be reduced in the long term. On the other hand, inappropriate seating is one of the factors that not only impacts MSDs but also decreases job satisfaction [39].

In conclusion, prolonged sitting during taxi driving and the pressure exerted when using the clutch lead to significant musculoskeletal pain, particularly in the lower back. Although taxi drivers maintain a proper back posture with support from the chair, the extended periods of sitting eventually result in musculoskeletal discomfort in the lower back. Additionally, the knees remain in a bent position for extended periods during driving, which leads to improper posture. The continuous bending and pressure applied during clutching contribute to additional strain on the knees. It can be suggested that increasing rest periods and reducing working hours for drivers could reduce the pressure on the back and knees. Furthermore, appropriate exercises aimed at strengthening the back and leg muscles can help support the spine and knees.

Our study showed that there was agreement between the methods WERA and ART, as both indicated a moderate risk for MSDs. WERA assesses shoulders, wrists, back, neck, knees, load handling, vibration, and contact stress, while ART focuses more on the upper body, evaluating arms, wrists, fingers, and load handling. Although ART does not assess knees, its results aligned with those of WERA. However, the knees are one of the body parts that are heavily used in driving. Also, our results showed that the average intensity of pain in the drivers’ knees according to the body map questionnaire was the highest after the back. Therefore, in the evaluation of MSDs in drivers, a method that evaluates the legs, especially the knees, should be used. Based on this, although the results of the WERA and ART were close to each other, the former is a more reliable method for the assessment of MSDs in the driver community.

In QEC, posture assessment is limited to the shoulders, wrists, neck, and back. Although factors, such as load handling, vibration, visual demands, and stress, are self-reported by participants in the second questionnaire, this self-reporting has lower reliability compared to evaluations performed by experts. Although QEC can be considered a complete assessment of MSDs, because it examines both physical and psychological factors, the self-report part of this questionnaire can directly affect the final risk assessment [33]. This aspect may be influenced by the individual’s condition, and as a result, the assessment of the risk of MSDs may be misguided.. Therefore, although the QEC method is one of the proposed approaches for evaluating MSDs, as a standalone method, it is not completely accurate or efficient and does not provide a fully reliable report. This assertion was clearly demonstrated in our results, as WERA and ART reported more similar outcomes than QEC.

This study has some limitations that may affect the findings. Due to the limited sample of urban taxi drivers, the results may not be fully representative of all drivers, as weather conditions and traffic vary by region. Weather changes, such as snow and rain, as well as working on busy roads, can prolong routes and lead to increased driving time, which may contribute to a higher incidence of MSDs. Furthermore, because of the busy and impatient nature of the target group, the study only included 140 drivers, which may not be sufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The sample size was small due to limited access to participants. Urban taxi drivers often work long and irregular hours, making it challenging to attract a sufficient number of participants within the given timeframe, resulting in the study being conducted with a minimal sample size.

Conclusion

The results of the assessment using the risk evaluation methods—WERA, ART, QEC—and the Body Map Questionnaire indicated that the highest risk of MSDs occurred in the lower back and knees, with participants reporting greater pain intensity in these areas. Since prolonged sitting and pressure on pedals increase the severity of pain in the lower back and knees, increasing rest periods and reducing working hours can help alleviate these issues. Additionally, while both WERA and ART showed a medium level of risk, QEC indicated a low risk level, leading to the conclusion that WERA and ART are more consistent with each other. Based on the evaluation results and the body areas assessed by each method, it can be inferred that, given the high prevalence of MSDs in the lower back and lower extremities among taxi drivers, a method focusing on these areas is of greater importance. Also, contrary to QEC, WERA lacks a self-reporting section, which can have a negative effect on the main result of assessing the risk of MSDs. Thus, it can be said that WERA is a more acceptable method for examining MSDs in the drivers’ community. Since WERA includes an assessment of legs and knees, its application to evaluate MSDs among drivers can be considered both effective and practical.

Also, since our results showed that MSDs in the knees and back are more common among drivers, it is suggested that drivers keep their knees in a straight position during rest. Also, using standard pillows can support drivers’ backs. It is recommended to avoid uninterrupted driving. Using a rhythm of rest and intermittent work can help reduce musculoskeletal pain in this occupational group.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1403.078). All participants were informed about the objectives and procedures of the study, and their consent was obtained through signed informed consent forms. Participants were assured that their information would remain completely confidential and would only be used for research purposes.

Funding

This article is the result of a research project and financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted among taxi drivers in Tehran. The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Research Deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, the Occupational Health Department of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, and all participants in this research for their valuable contributions.

References

- Askari A, Babahaji M,Majdabadi HA, Nouri M, Namaki SA, Karami H, et al. Association of backpacks carriage manner (BCM) and musculoskeletal symptoms among students facilitating health promotion: Ergonomics design-based qualitative content analysis study. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 14(1):372. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_409_24]

- Khandan M, Eyni Z, Ataei manesh L, Khosravi Z, Biglari H, Koohpaei AR, et al. Relationship between musculoskeletal disorders and job performance among nurses and nursing aides in main educational hospital in Qom Province, 2014. Research Journal of Medical Sciences. 2016; 10(4):307-12. [Link]

- SheikhMozafari MJ, Mirnajafi ZF, Sasani NN, Mohammad AP, Biganeh J, Zakerian SA. [Investigating the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and its relationship with physical and psychosocial risk factors among an automotive industry employees: Validating the MDRF questionnaire (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Safety at Work. 2023; 13(4):714-35. [Link]

- Jafari Kafash K, Pashapour V, Babaei Pouya A, Nouri M, PourSadeghiyan M, Hekmatfar S. Awareness of ergonomic principles and implementation of asana practices among dental clinic professions in Iran. Physical Treatments. 2025; 15(4):375-86. [DOI:10.32598/ptj.15.4.684.1]

- Gill TK, Mittinty MM, March LM, Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Cross M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2023; 5(11):e670-82. [Link]

- Yarmohammadi H, Niksima SH, Yarmohammadi S, Khammar A, Marioryad H, Poursadeqiyan M. [Evaluating the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in drivers systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Safety at Work. 2019; 9(3):221-30. [Link]

- Bahrami F, Zandsalimi F, Rahmani R, Moradian Haft Cheshmeh Z. Study of pain and disabilities in musculoskeletal system among urban bus drivers with respect to body postures, job satisfaction, and individual factors. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2024;11(1):74-83. [Link]

- Khandan M, Ataei Manesh L, Eyni Z, Khosravi Z, Biglari H, Koohpaei AR, et al. Relationship between Job content and Demographic Variables with Musculoskeletal Disorders among Nurses in a University Hospital, Qom Province, 2014. Research Journal of Applied Sciences. 2016; 11(7):547-53. [Link]

- Joseph L, Standen M, Paungmali A, Kuisma R, Sitilertpisan P, Pirunsan U. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among professional drivers: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Health. 2020; 62(1):e12150. [DOI:10.1002/1348-9585.12150] [PMID]

- Kamble R, Pandit S, Sahu A. Occupational ergonomic assessment of MSDs among the artisans working in the Bagh hand block printing industry in Madhya Pradesh, India. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2023; 29(3):963-9. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2022.2090120] [PMID]

- Okunribido OO, Magnusson M, Pope M. Delivery drivers and low-back pain: A study of the exposures to posture demands, manual materials handling and whole-body vibration. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2006; 36(3):265-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2005.10.003]

- Maduagwu SM, Galadima NM, Umeonwuka CI, Ishaku CM, Akanbi OO, Jaiyeola OA, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among occupational drivers in Mubi, Nigeria. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2022; 28(1):572-80. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2020.1834233] [PMID]

- Benstowe SJ. Long driving hours and health of truck drivers [MA thesis]. New Jersey: New Jersey Institute of Technology; 2008. [Link]

- Mozafari A, Vahedian M, Mohebi S, Najafi M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in truck drivers and official workers. Acta Medica Iranica. 2015; 53(7):432-8. [Link]

- Arghami S, Kamali K, NasabAlhosseini M. [A survey on musculoskeletal pain in suburban bus drivers (Persian)]. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2015; 2(2):72-81. [Link]

- Bevan S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2015; 29(3):356-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.berh.2015.08.002] [PMID]

- Barzegari Bafghi MA, Sahlabadin A, Mokhlisi M, Tori G. [Examining the work status of 0457 bus drivers of a single company using the RULA method and its compliance with the Body Map questionnaire (Persian)]. Paper presented at: The Fourth Nationwide Conference on Professional Health of Iran. 2004 October 4; Hamedan, Iran. [Link]

- Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sørensen F, Andersson G, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Applied Ergonomics. 1987; 18(3):233-7. [DOI:10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X] [PMID]

- Salehi Sahlabadi A, Azrah K, Mehrifar Y, Poursadeghiyan M. Evaluation of health risk experienced by urban taxi drivers to whole-body vibration and multiple shocks. Noise & Vibration Worldwide. 2024; 55(6-7):296-303. [DOI:10.1177/09574565241252992]

- Soltaninejad M, Yarmohammadi H, Madrese E, Khaleghi S, Poursadeqiyan M, Aminizadeh M, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in drivers: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Work. 2020; 67(4):829-35. [DOI:10.3233/WOR-203335] [PMID]

- Karchani M, Mazloumi A, NaslSaraji G, Akbarzadeh A, Niknezhad A, Ebrahimi MH, et al. Association of subjective and interpretive drowsiness with facial dynamic changes in simulator driving. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2015; 15(4):250-5. [PMID]

- Biglari H, Ebrahimi MH, Salehi M, Poursadeghiyan M, Ahmadnezhad I, Abbasi M. Relationship between occupational stress and cardiovascular diseases risk factors in drivers. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2016; 29(6):895-901. [DOI:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00125] [PMID]

- Palikhe S, Lee JY, Kim B, Yirong M, Lee DE. Ergonomic risk assessment of aluminum form workers’ musculoskeletal disorder at construction workstations using simulation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4356. [DOI:10.3390/su14074356]

- Motamedzade M, Mohammadian M, Faradmal J. Comparing of four ergonomic risk assessment methods of hal-tlv, strain index, ocra checklist, and art for repetitive work tasks. Iranian Journal of Health, Safety and Environment. 2019; 6(3):1303-9. [Link]

- Escalante A, Lichtenstein MJ, White K, Rios N, Hazuda HP. A method for scoring the pain map of the McGill pain questionnaire for use in epidemiologic studies. Aging. 1995; 7(5):358-66. [DOI:10.1007/BF03324346] [PMID]

- Zare M. Eshaghi Sani Kakhaki H, Kazempour M, Behjati Ardakani M. [Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in primary school students in Abu Musa Island (Persian)]. Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2022; 9(3):268-79. [Link]

- Brummett CM, Bakshi RR, Goesling J, Leung D, Moser SE, Zollars JW, et al. Preliminary validation of the Michigan Body Map. Pain. 2016; 157(6):1205-12. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000506] [PMID]

- Foxen-Craft E, Scott EL, Kullgren KA, Philliben R, Hyman C, Dorta M, et al. Pain location and widespread pain in youth with orthopaedic conditions: Exploration of the reliability and validity of a body map. European Journal of Pain. 2019; 23(1):57-65. [DOI:10.1002/ejp.1282] [PMID]

- Abdol Rahman MN. Development of an ergonomic risk assessment tool for work postures [doctoral dissertation]. Johor Bahru: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia; 2014. [Link]

- Li G, Buckle P. A practical method for the assessment of work-related musculoskeletal risks - Quick Exposure Check (QEC). Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 1998; 42(19):1351-5. [DOI:10.1177/154193129804201905]

- Hosseini MH. [Ergonomic evaluation of working conditions using QEC and ART methods and the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in a tile industry (Persian)]. Occupational Medicine Quarterly Journal. 2024; 16(1):43-52.[Link]

- Moradpour Z, Rezaei M, Torabi Z, Khosravi F, Ebrahimi M, Hesam G. [Study of correlation between muscle fatigue assessment and cornell musculoskeletal disorders questionnaire in Shahroud Taxi Drivers in 2017: A descriptive study (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2019; 17(11):1031-42. [Link]

- Bulduk EÖ, Bulduk S, Süren T, Ovalı F. Assessing exposure to risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders using Quick Exposure Check (QEC) in taxi drivers. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2014; 44(6):817-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2014.10.002]

- Rezaei E, Shahmahmoudi F, Makki F, Salehinejad F, Marzban H, Zangiabadi Z. Musculoskeletal disorders among taxi drivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders,. 2024; 25(1):663. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-024-07771-w] [PMID]

- Omidianidost A, Hosseini S, Jabari M, Poursadeghiyan M, Dabirian M. The relationship between individual, occupational factors and LBP (low back pain) in one of the auto parts manufacturing workshops of Tehran in 2015. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. 2016; 11(5):1074-7. [Link]

- Mazloumi A, Kazemi Z, Aghazade SR, Miri M, Shirmohammadi H. Ergonomic assessment of clutch pedal in some common models of vehicles in taxi routes in Tehran. Iran Occupational Health. 2018; 14(6):1-10. [Link]

- Ahmad I, Balkhyour MA, Abokhashabah TM, Ismail IM, Rehan M. Occupational musculoskeletal disorders among taxi industry workers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia. 2017; 14(2):593-606. [DOI:10.13005/bbra/2483]

- Sharma G, Ahmad S, Mallick Z, Khan ZA, James AT, Asjad M, et al. Risk factors assessment of musculoskeletal disorders among professional vehicle drivers in India using an ordinal priority approach. Mathematics. 2022; 10(23):4492. [DOI:10.3390/math10234492]

- Joseph L, Vasanthan L, Standen M, Kuisma R, Paungmali A, Pirunsan U, et al. Causal relationship between the risk factors and work-related musculoskeletal disorders among professional drivers: A systematic review. Human Factors. 2023; 65(1):62-85. [DOI:10.1177/00187208211006500] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Sport injury and corrective exercises

Received: 2024/11/20 | Accepted: 2025/01/20 | Published: 2026/01/1

Received: 2024/11/20 | Accepted: 2025/01/20 | Published: 2026/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |