Thu, Feb 19, 2026

Volume 16, Issue 1 (Winter 2026)

PTJ 2026, 16(1): 39-48 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

kalantariyan M, Minoonejad H, Rajabi R, Seidi F. Comparative Effects of Wobble Board and TRX Training on Balance in Athletes With Functional Ankle Instability. PTJ 2026; 16 (1) :39-48

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-681-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-681-en.html

1- Department of Sport Injury and Corrective Exercises, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Health and Sport Medicine, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Health and Sport Medicine, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 529 kb]

(600 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1506 Views)

Full-Text: (538 Views)

Introduction

Frequent and chronic lateral ankle ligament sprains can lead to functional ankle instability [1], a condition that is particularly prevalent in athletes who perform dynamic activities, such as jumping and cutting [1]. This injury is the most common type of sports injury, as confirmed by epidemiological studies [2].

Freeman’s hypothesis regarding proprioceptive deficits offers a conceptual basis for comprehending how impairments in sensory feedback contribute to ankle instability [3]. Additionally, further research has demonstrated that delayed muscle activation and diminished muscle strength are key neuromuscular factors that intensify this condition [4, 5]. Functional ankle instability, resulting from a combination of factors, such as proprioception deficits and muscle weakness, can significantly impact balance [4, 5]. Athletes with this condition may struggle to maintain their center of gravity within their base of support, which can affect their performance and increase the risk of injury [6]. Research has consistently found that individuals with functional ankle instability exhibit deficits in both static and dynamic balance, as assessed in both laboratory and field tests [7, 8]. This highlights the direct relationship between ankle instability and balance impairment [6-8]. Given the strong link between balance impairment and recurrent ankle sprains, addressing balance deficits is crucial for individuals with functional ankle instability [9]. Balance impairment has been shown to significantly increase the risk of lower-limb injuries, with individuals experiencing up to five times more injuries compared to those with good balance [9, 10]. This highlights the importance of incorporating balance-enhancing strategies into rehabilitation programs for athletes with functional ankle instability.

Neuromuscular exercises are a valuable tool for rehabilitating balance impairments in individuals with functional ankle instability [11]. These exercises, which target the motor control system, can help improve sensory-motor integration and coordination. Wobble boards are a type of neuromuscular exercise that has gained significant attention in both sports and medical communities in recent decades [12-14]. Although the individual impact of wobble board and TRX training on balance is well-documented, this study distinctively examined their comparative effectiveness and evaluated the sustainability of their benefits after a period of de-training [7, 14, 15]. These exercises are often considered the gold standard for the rehabilitation of this condition [14]. However, more research is needed to understand the long-term benefits of using wobble boards and the importance of persistence in maintaining these exercises.

TRX exercises have emerged as a popular method of strength training in recent years, attracting interest from both athletes and fitness enthusiasts. These exercises are widely used in clinical and sports settings [16, 17]. The ease of use, versatility, and accessibility of TRX exercises make them appealing for people of all ages and fitness levels [18, 19]. These exercises effectively target and activate the core muscles, which is a key benefit for improving overall strength and stability [17]. It has been shown that the core muscles play a crucial role in maintaining balance and proper function of the lower limbs during sports activities [20]. Strength training with TRX has been shown to improve muscle strength and activate proprioceptive receptors, which are crucial for maintaining balance and proper function of the lower limbs during sports activities [21]. While TRX suspension training incorporates a broad range of physical exercises, this study specifically focused on exercises aimed at enhancing proprioception, dynamic balance, and neuromuscular coordination. By concentrating on these targeted exercises, the study provides valuable insights for rehabilitation professionals and sports trainers. Despite the proven effectiveness of both wobble board and TRX training in improving balance, there is a limited number of comparative studies evaluating their relative efficacy in managing functional ankle instability. This research aimed to fill this gap by offering evidence-based recommendations for rehabilitation strategies and assessing the effectiveness of these training interventions on static and dynamic balance indices, including the retention of improvements after a period of de-training.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This quasi-experimental study was performed on 36 male college athletes aged 18-25 with functional ankle instability. To calculate the sample size, G*Power software, version 3.1 was used. Considering the study’s repeated measures ANOVA, a medium overall effect size of f=0.25, an α-error of 0.05, and a desired power (1-ß error) of 0.8, the total sample size resulted in thirty-six participants [22].

The sample consisted of university-level male athletes participating in basketball, volleyball, and handball. These sports require frequent cutting, jumping, and landing movements, which increase the likelihood of ankle sprains. Recruitment focused on these sports to ensure ecological validity for interventions targeting balance rehabilitation in athletes predisposed to ankle instability. Anthropometric data, including age, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI), were collected by the first author before the pre-test assessment, ensuring accuracy and consistency [23].

Participants were included in the study if they met the following criteria: Diagnosed with functional ankle instability; the ability to bear full weight on the affected limb; exhibiting normal gait patterns and complete ankle joint range of motion at the time of participation; a cumberland ankle instability tool (CAIT) score of <27 [24]; and absence of mechanical ankle instability, confirmed through negative anterior drawer and talar tilt tests [13, 23]. Additionally, participants were required to have no history of participating in structured ankle rehabilitation programs within the past six months. Exclusion criteria included the presence of pain that impaired participation in training sessions or assessments, any underlying musculoskeletal or neurological condition affecting lower-limb function, and failure to adhere to the intervention protocol, defined as missing more than two consecutive sessions or three non-consecutive sessions. Eligibility was determined by a licensed physical therapist with over 10 years of clinical experience (second author), who conducted comprehensive evaluations based on the aforementioned criteria. This ensured a consistent and rigorous screening process to recruit participants representative of the target population. While challenges related to managing inactivity periods during follow-up are recognized, these were addressed through regular monitoring and adherence checks to ensure consistency. Before the study, all participants provided written informed consent after being briefed on the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Preparation

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (wobble board training, TRX training, or control) using a computer-generated randomization sequence to minimize allocation bias. Before the pre-test session, all participants were instructed to wear comfortable, athletic clothing suitable for physical activity. Upon arrival, they completed baseline documentation to confirm their eligibility on the testing day. To ensure consistency, a standardized 5-minute warm-up protocol was conducted under the supervision of the first author. This warm-up included dynamic lower-limb exercises, such as controlled leg swings, walking lunges, and ankle mobilization stretches to reduce the risk of injury and prepare the participants for subsequent balance testing. Participants were then familiarized with the testing equipment and procedures, ensuring they understood the requirements and could perform the tasks correctly.

Evaluation of balance indices

Balance indices were measured using the Biodex balance system SD, which quantifies static and dynamic balance on a 12-level adjustable platform. Lower scores indicate better balance performance, reflecting reduced sway and improved stability. The tool was calibrated before each use to ensure reliability [25]. The Biodex balance system was used to conduct the dynamic balance test at level 4 instability. Testing was performed in double-leg stance situation, with the participant standing barefoot in a neutral position. The feet were positioned according to the system’s alignment grid to ensure standardization across all trials. To assess dynamic balance, participants performed a balance test on an unstable platform for 20 seconds in different directions. Each participant performed the test three times, and the average score was recorded. A 30-second break was taken between each repetition. For static balance, the platform was stabilized, and participants performed the same test.

TRX exercise intervention

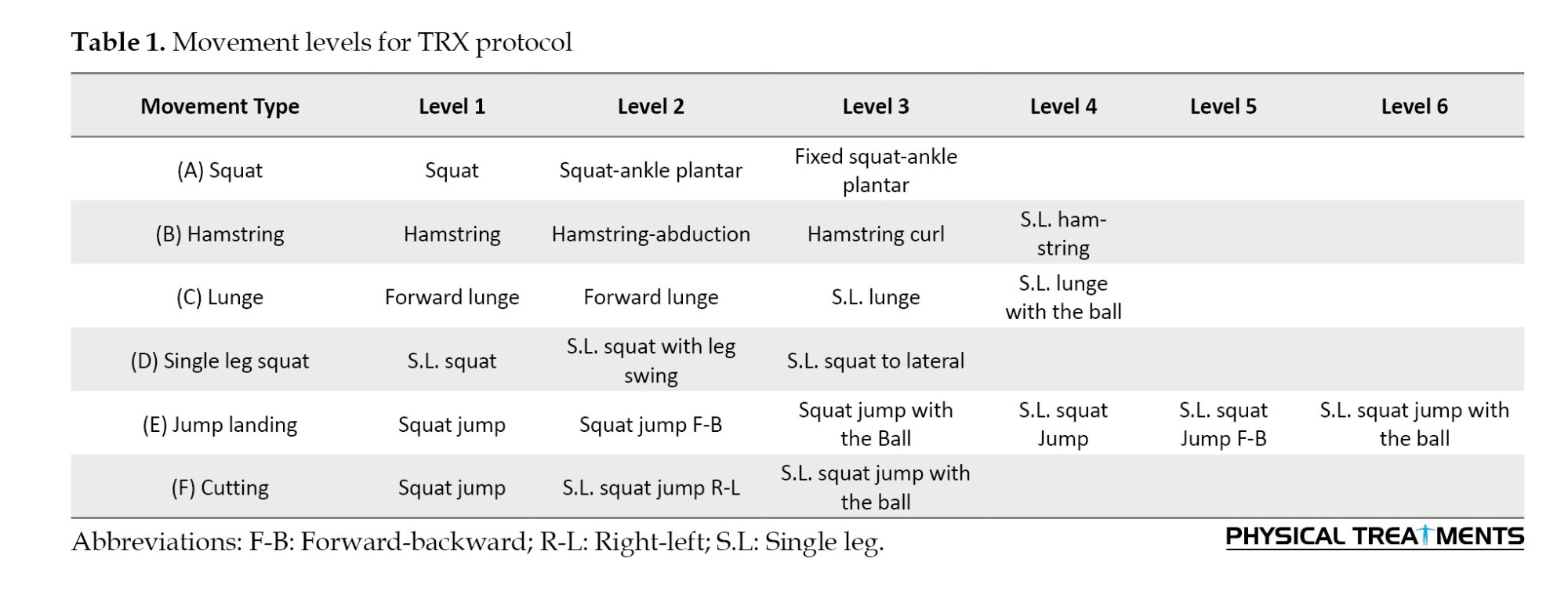

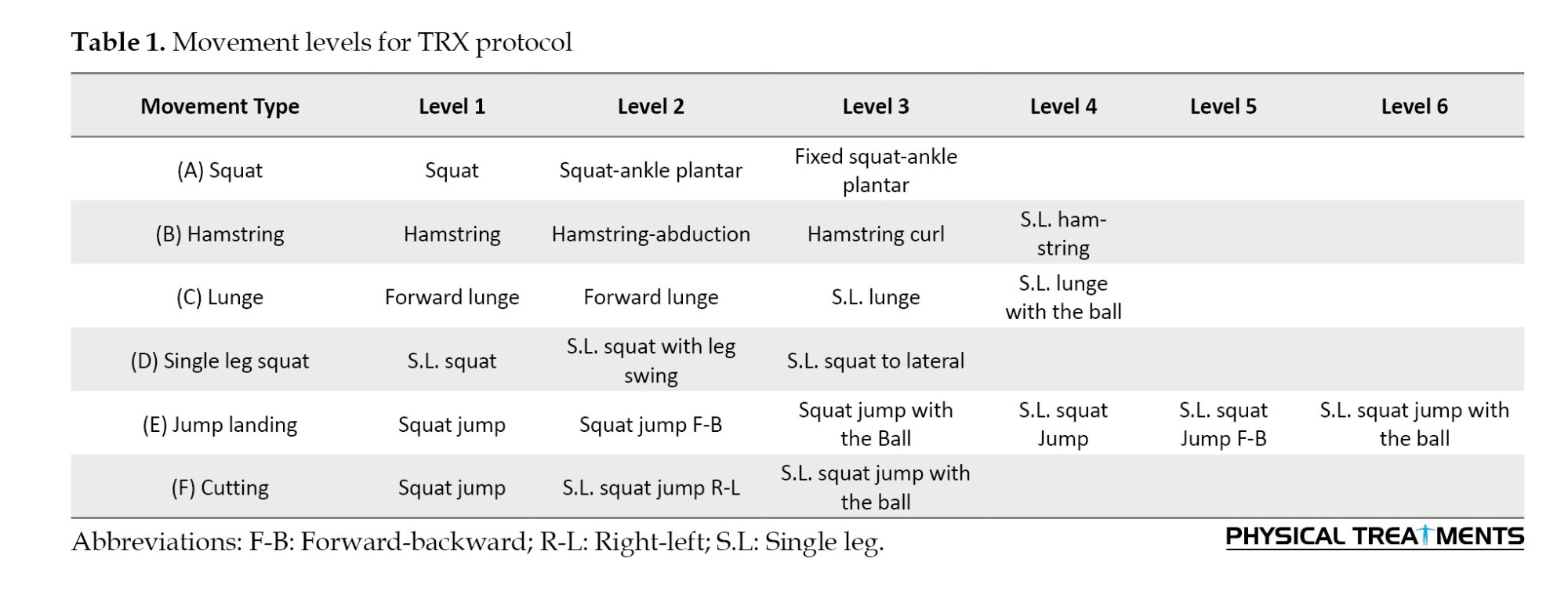

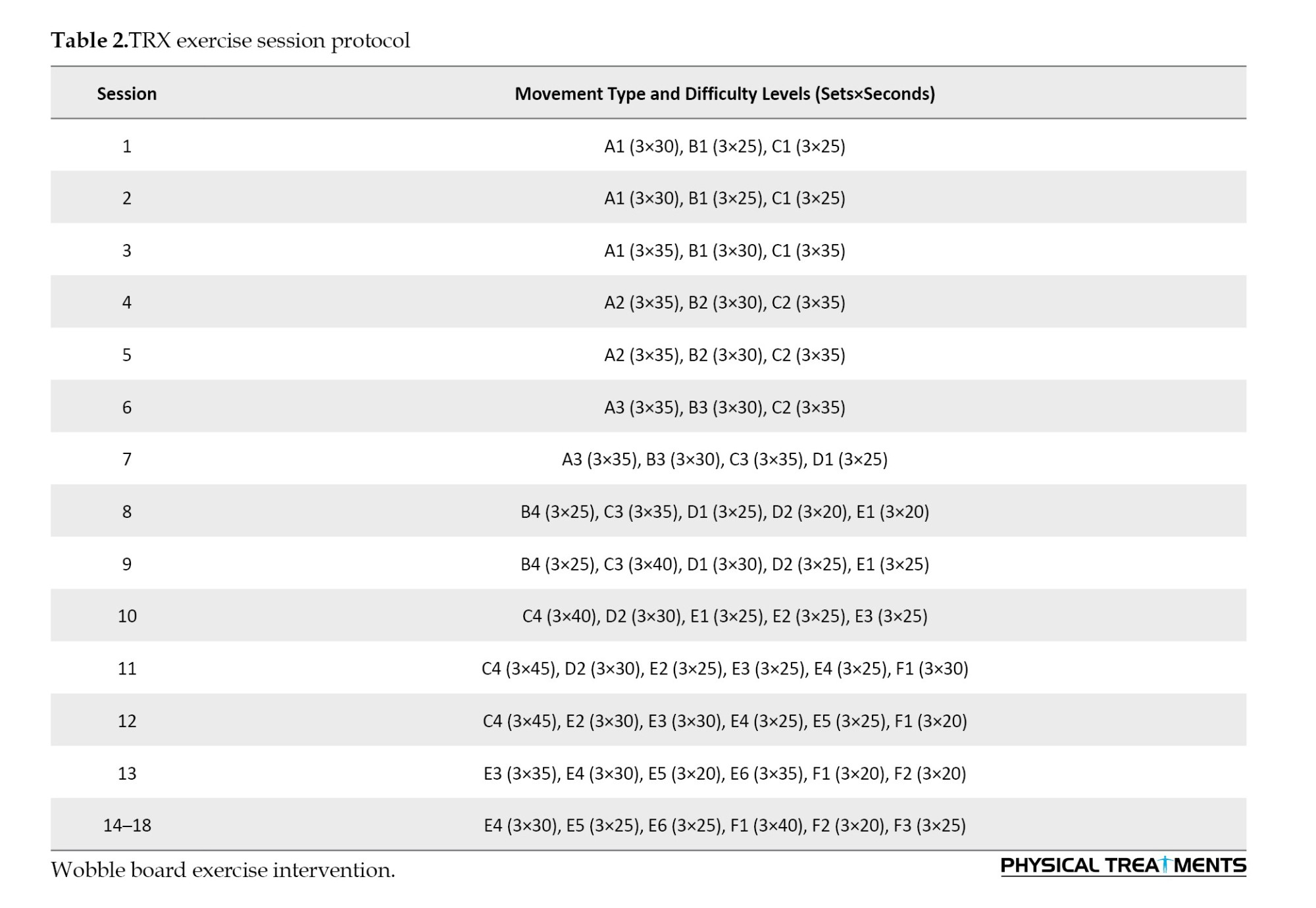

After completing the pre-test assessments, participants in the experimental groups undertook a structured TRX training program, conducted three times per week over a six-week period on non-consecutive days. To maintain consistency, all training sessions were scheduled at the same time each day. Each session consisted of a standardized 10-minute warm-up, followed by 15–20 minutes of TRX suspension exercises, and concluded with a 5-minute cool-down routine. To ensure proper execution and minimize injury risk, participants completed two familiarization sessions prior to the intervention. The TRX exercise protocol was developed based on established guidelines and peer-reviewed literature on suspension training [26-29]. Exercises targeted major muscle groups and incorporated movements across multiple anatomical planes to simulate functional and sport-specific demands. The training sessions were conducted using the TRX PRO3 suspension trainer system (fitness anywhere LLC, USA), with the equipment securely mounted on a rod 2.5 meters above the ground. Progression in exercise intensity followed the principles of the FITT model (frequency, intensity, time, and type), advancing through five to six difficulty levels. These levels ranged from beginner (levels 1–2) to advanced (levels 5–6), with difficulty adjusted by modifying suspension angles, exercise duration, and dynamic complexity. The progression protocol was carefully designed to ensure a gradual increase in challenge and was validated by a specialist physician [29] (Tables 1 and 2).

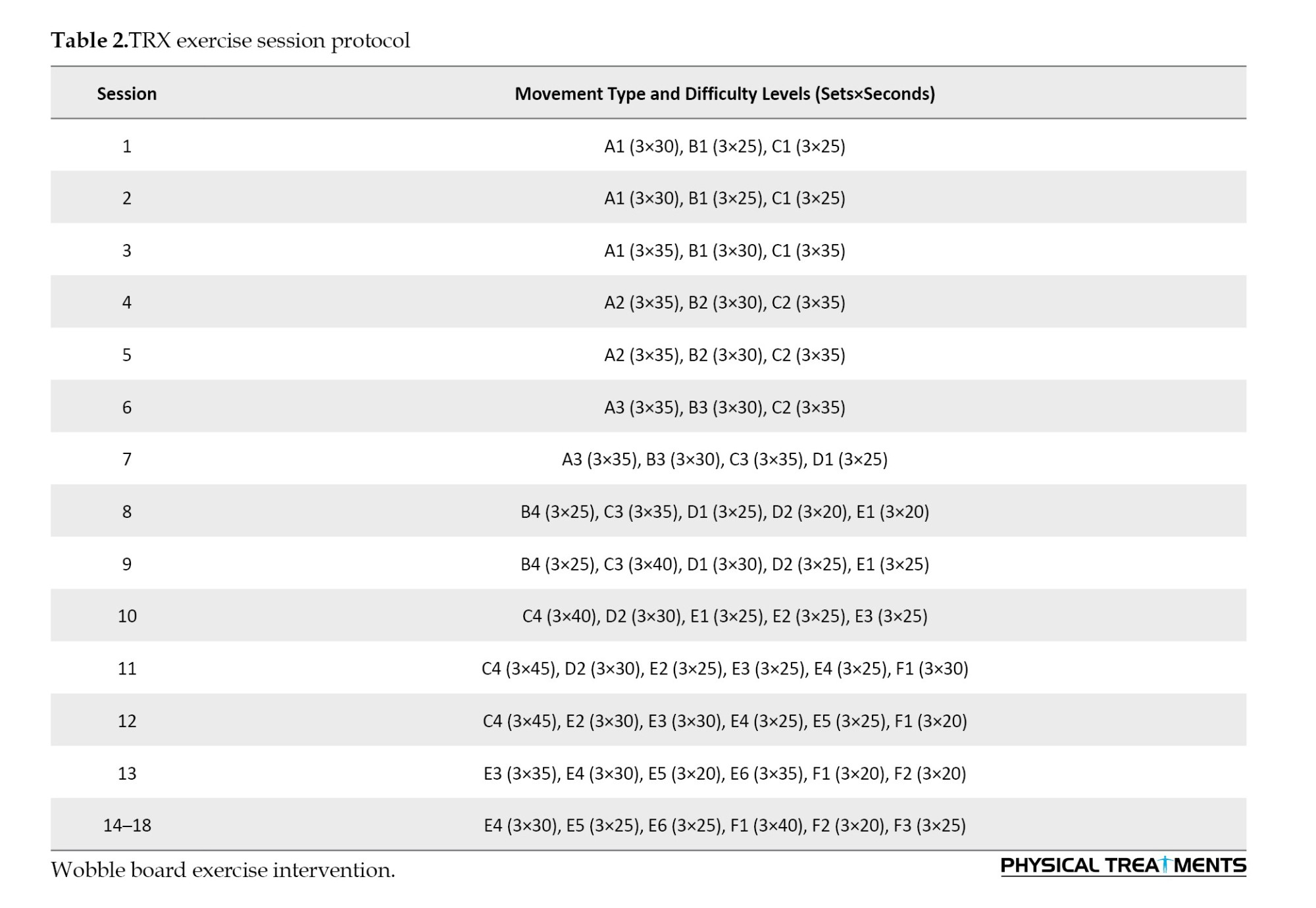

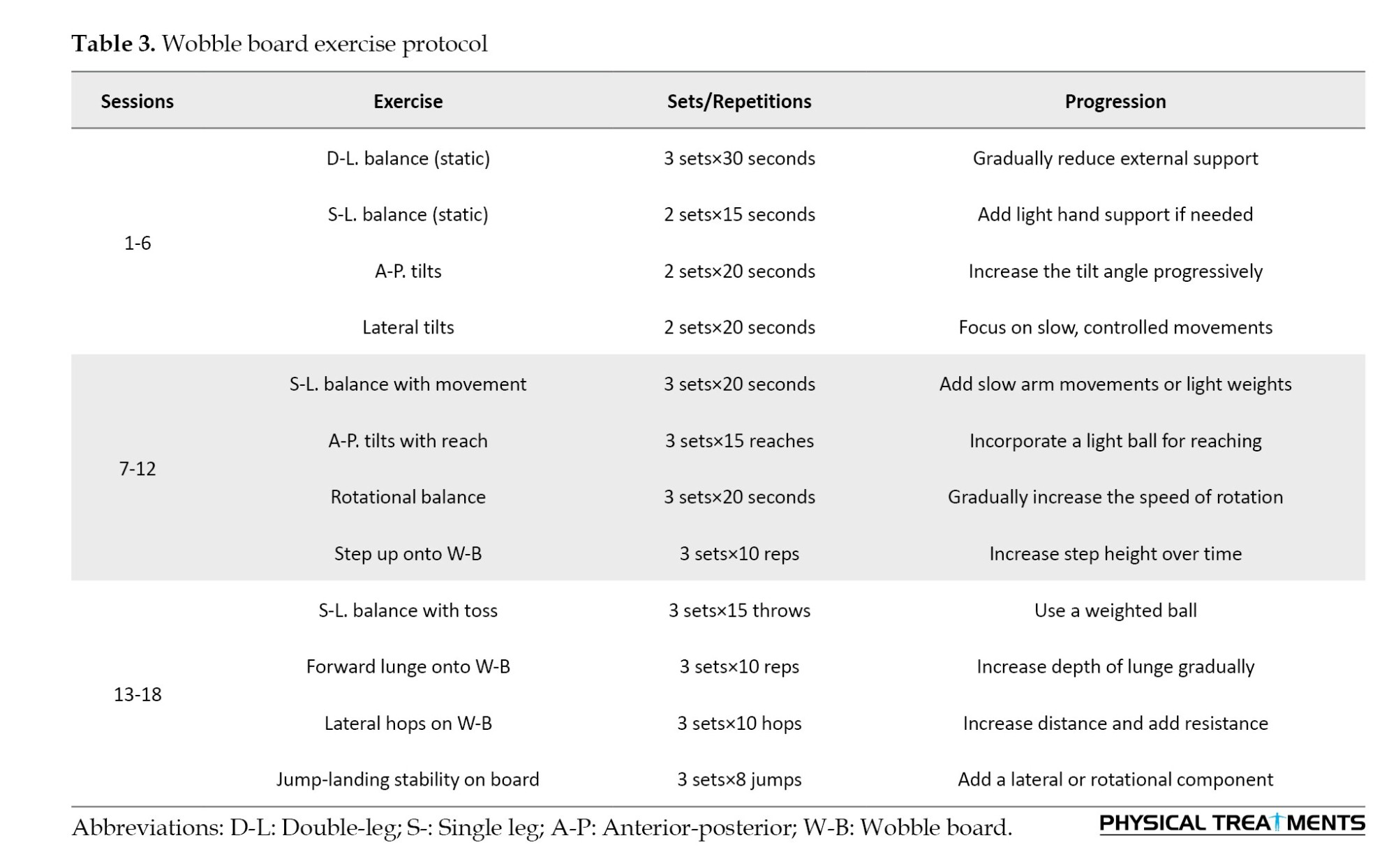

The wobble board exercise intervention was conducted over six weeks, with participants completing three sessions per week on non-consecutive days. Each session lasted approximately 30 minutes, starting with a 10-minute warm-up, followed by the main training segment, and concluding with a 5-minute cool-down to promote recovery. To ensure familiarity with the exercises and proper execution, participants underwent two supervised familiarization sessions prior to the intervention. The exercise protocol was adapted from the established methodology of Clark and Burden [12], which has been widely applied in research on functional ankle instability rehabilitation. The protocol focused on progressively challenging static and dynamic balance through controlled movements performed on an unstable surface. The intervention utilized a wobble board with an adjustable tilt angle to tailor difficulty levels as participants advanced through the program. The core training segment (15–20 minutes) involved exercises targeting proprioception, postural control, and neuromuscular adaptation. These exercises included bilateral and unilateral stance tasks, dynamic weight shifts, controlled rotations, and reaching tasks while maintaining stability. Progression followed the principles of the FITT model (frequency, intensity, time, and type), ensuring a gradual increase in challenge by modifying the tilt angle, duration, and complexity of the tasks. For instance, early stages (weeks 1–2) consist of static exercises with a low tilt angle to develop foundational stability, intermediate stages (weeks 3–4) consist of dynamic exercises with an increased tilt angle to challenge dynamic postural control, and advanced stages (weeks 5–6) consist of functional and sport-specific tasks performed with a high tilt angle to simulate real-world balance demands. All sessions were conducted under the supervision of a trained researcher to ensure adherence to proper technique and progression (Table 3).

Participants in the control group were instructed to refrain from engaging in any sports activities throughout the study period and were advised to continue their usual daily routines without modifications. At the end of the training period, balance indices of all subjects were reassessed with the same procedure as the pre-test. Also, in order to assess the persistence of exercises, balance tests were repeated 6 weeks after the post-test.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Subsequently, mixed repeated-measures ANOVA was applied to analyze intergroup comparisons, and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted to assess specific group differences. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 21, with the significance level set at 0.05.

Results

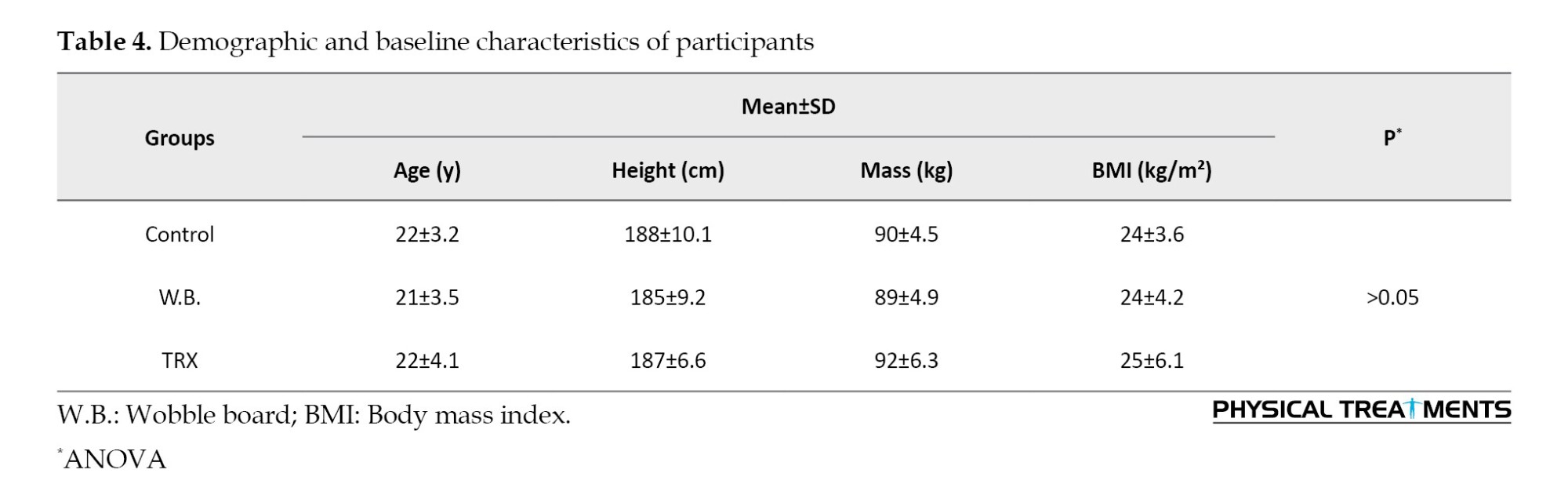

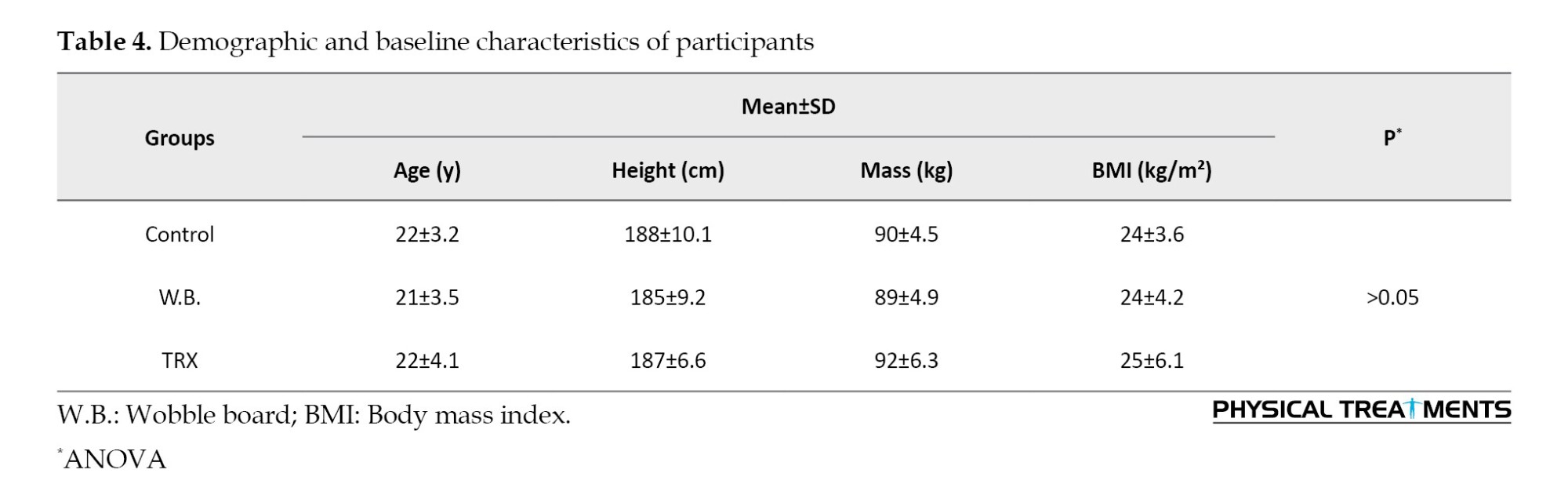

The demographic characteristics of participants showed no significant differences among the three groups, confirming homogeneity at baseline (P>0.05, Table 4). The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the data followed a normal distribution, justifying the use of parametric statistical methods.

The pre-test balance indices, including static and dynamic measures, revealed no significant differences across the three groups in all directions (anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, and overall; P≥0.05). This confirms comparable baseline balance abilities among the groups before the intervention.

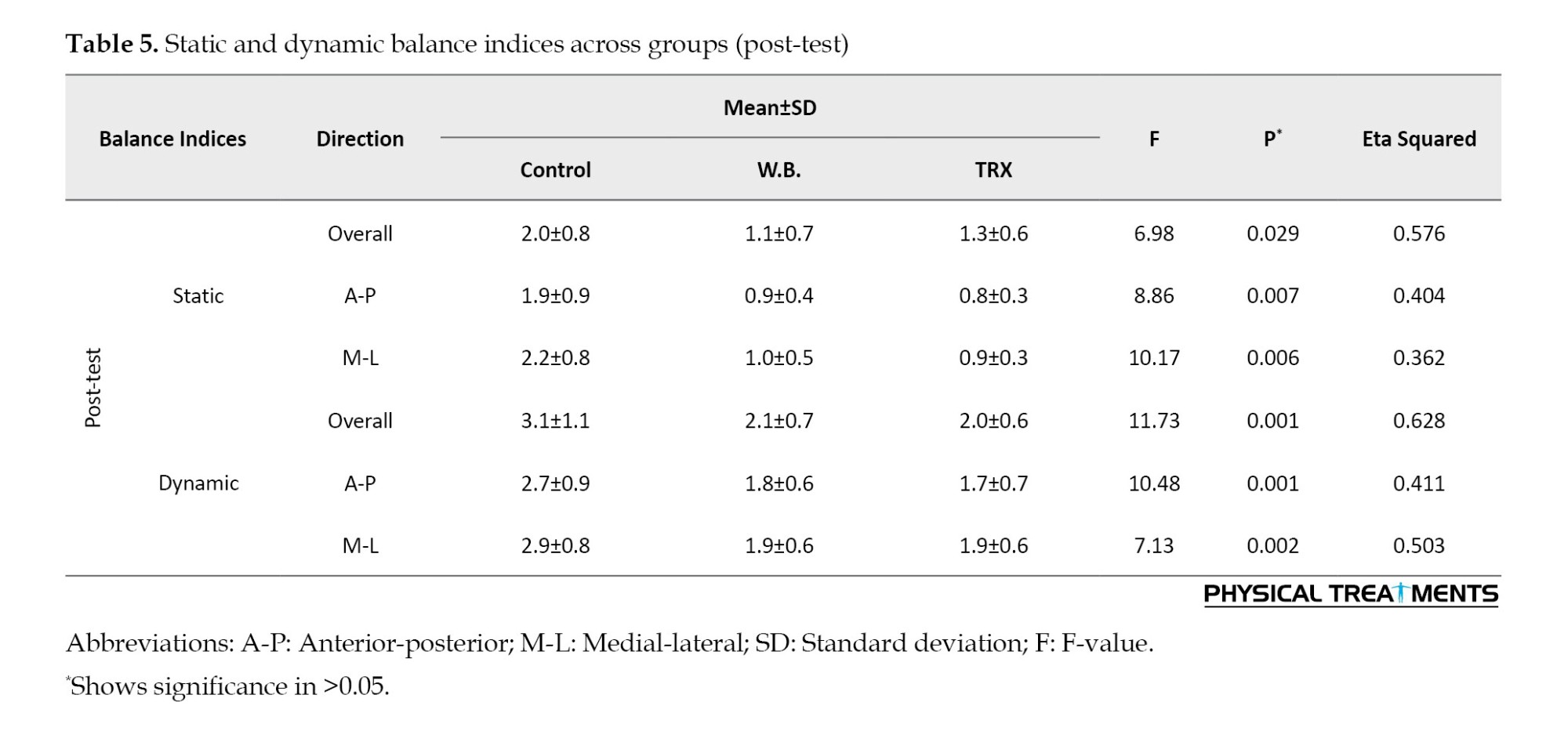

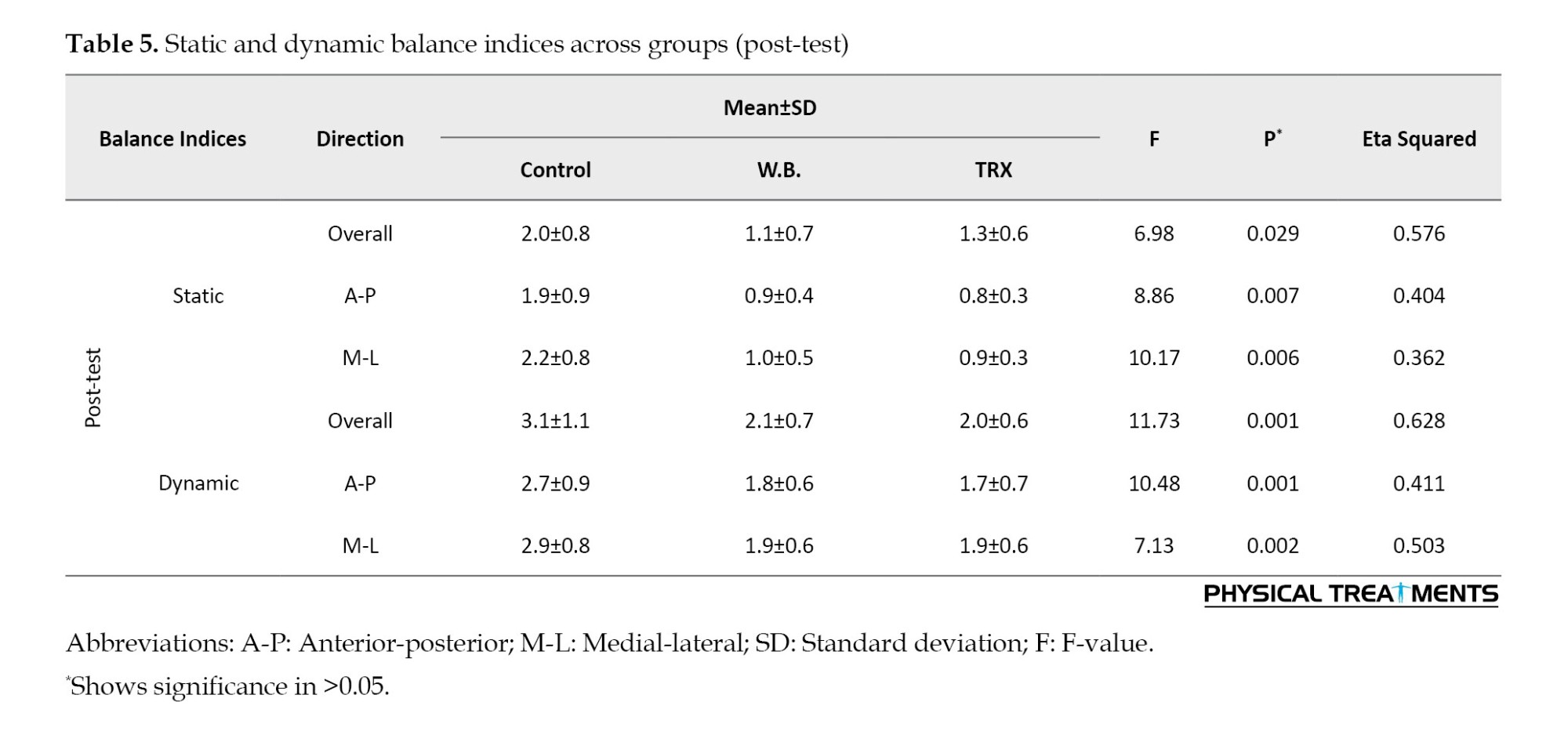

The repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated significant improvements in both static and dynamic balance indices for the wobble board and TRX groups in the post-test and follow-up stages compared to the pre-test stage (P≤0.05). Conversely, no significant changes were observed in the control group across any time point (P>0.05). Table 5 presents the comparison of balance indices across the three groups.

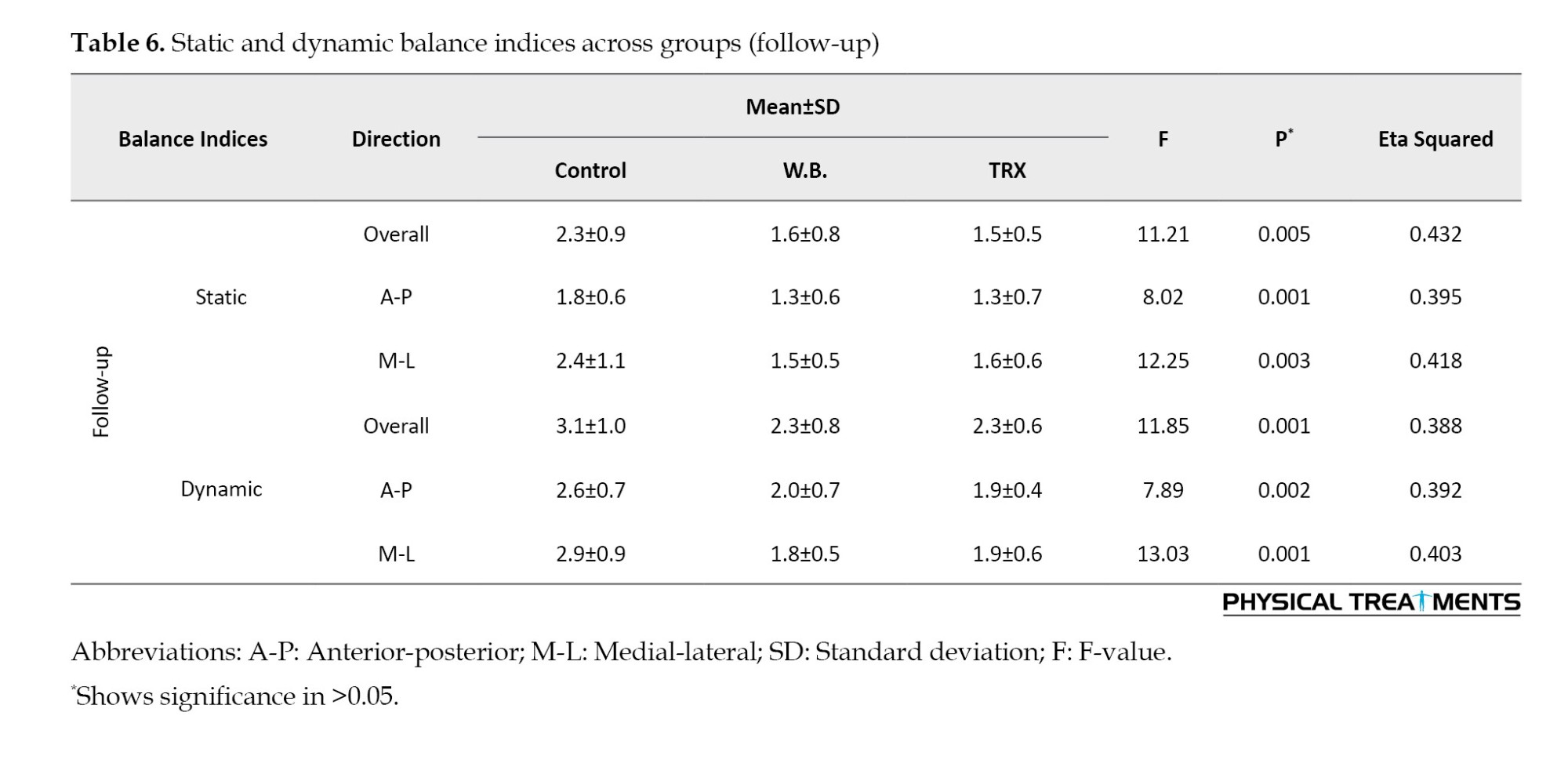

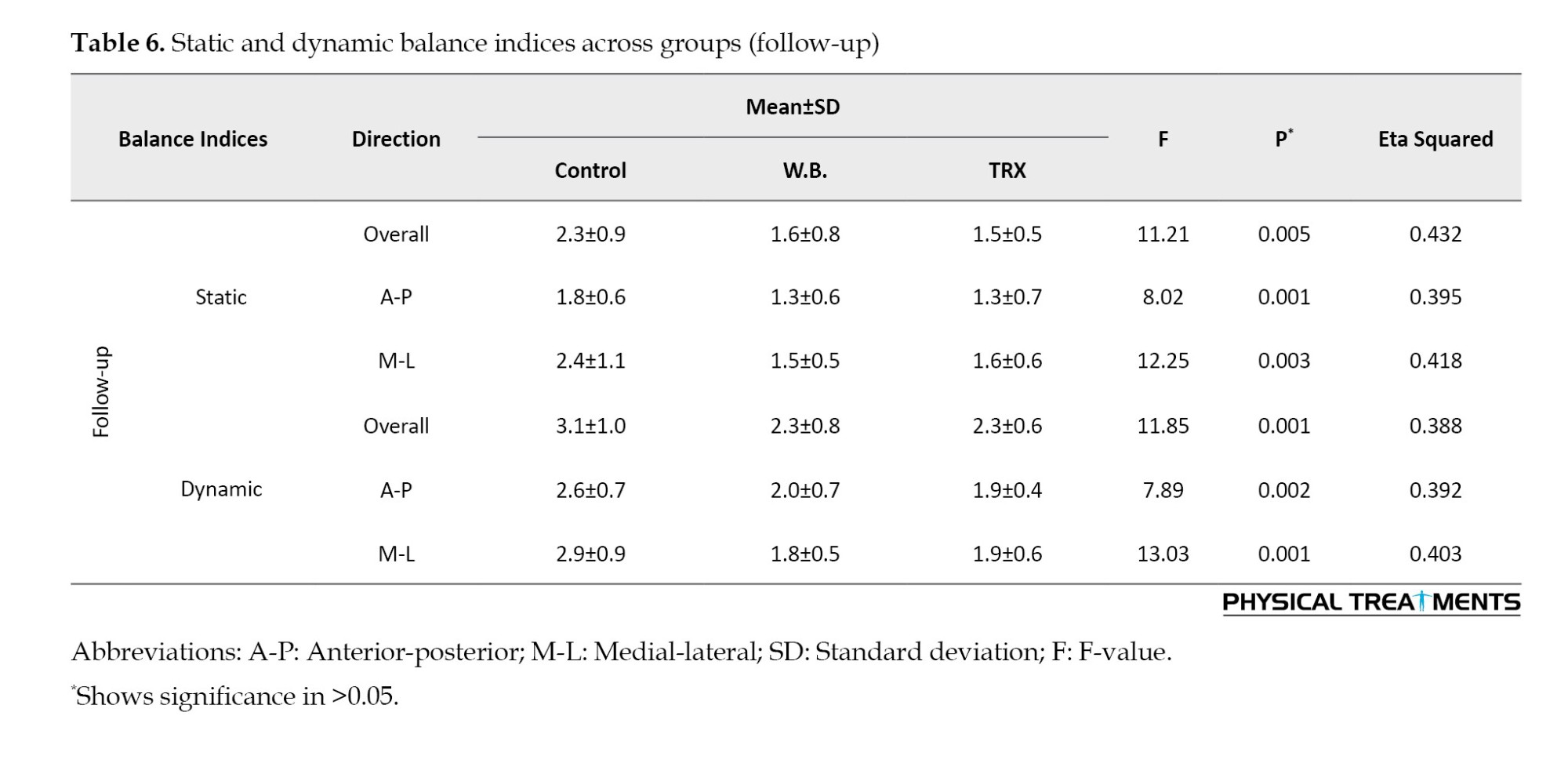

The Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated that both wobble board and TRX training significantly outperformed the control group in improving balance indices in all directions during the post-test and follow-up stages (P≤0.05). However, no significant differences were found between the wobble board and TRX groups, suggesting comparable effectiveness of both interventions. The observed effect sizes (eta squared) for balance improvements in the wobble board and TRX groups were moderate to large, reflecting substantial benefits from both interventions. Improvements persisted during the follow-up stage, indicating the retention of training effects six weeks after the post-test stage (Table 6).

Discussion

Our results showed that both wobble board and TRX training programs improved the static and dynamic balance indices in the athletes with functional ankle instability. One possible reason for the improved balance capabilities of the subjects in the present study is the increase in neuromuscular adaptations induced by the training [11]. This study highlights the comparative advantages of wobble board and TRX training for rehabilitating balance in athletes with functional ankle instability. Both methods effectively improve balance, yet their mechanisms and focus differ. Wobble board exercises excel in improving balance by enhancing proprioceptive control at the ankle joint [7]. They are particularly effective in the early stages of rehabilitation, where athletes need to rebuild their stability and reduce postural sway [27]. In contrast, TRX training offers superior dynamic balance improvements due to its integration of core stability, strength, and functional movement patterns [26]. These exercises mimic the demands of athletic performance, making them highly relevant for late-stage rehabilitation and return to sport protocols [7].

Wobble board exercise is a neuromuscular activity designed to improve proprioception and joint stability by challenging balance on an unstable surface [28]. Standing on an unstable surface during wobble board exercises stimulates mechanoreceptors in the ankle joint, such as Ruffini endings, Pacinian corpuscles, and Golgi tendon organs [7]. These receptors detect changes in joint position and movement, sending signals to the central nervous system. Thus, the enhanced proprioceptive feedback improves sensory-motor integration, enabling quicker and more accurate neuromuscular responses to perturbations [11]. By requiring constant adjustments to maintain stability, wobble board exercises engage the stabilizing muscles surrounding the ankle joint [14]. Repeated exposure to unstable conditions enhances the motor control strategies required to maintain balance. This leads to a reduction in postural sway and an improved ability to stabilize the center of gravity over the base of support [15]. The targeted nature of wobble board training on joint proprioception and stabilizer muscle activation makes it particularly effective for balance improvements, especially during single-leg stance tasks [11].

TRX suspension training leverages body weight and gravity as resistance, emphasizing core stability, dynamic strength, and multi-planar movements [29]. TRX exercises uniquely engage core stabilizing muscles (e.g. rectus abdominis, transvers abdominis, obliques, and multifidus) by requiring the athlete to maintain alignment during suspension-based movements [20]. Strong core stability reduces the load on the lower extremities and enhances the kinetic chain’s ability to respond to balance challenges [17]. TRX exercises strengthen lower-limb muscles, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius, through functional movements, like squats, lunges, and planks [26].

These exercises improve dynamic balance by enhancing joint control during sport-specific movements [29]. According to the previous studies, one of the important consequences of functional ankle instability is muscle atrophy and a decrease in the muscle strength of the ankle joint. Therefore, the volume and strength of the lower extremity muscles play a crucial role in determining the displacement and velocity of the center of gravity [29]. By improving lower-limb muscle strength, individuals with functional ankle instability can counteract the muscle weakness that contributes to their condition and enhance their balance [7, 19]. Therefore, it is essential to use exercises that improve the strength of the lower-limb muscles during the rehabilitation of functional ankle instability. Similar to wobble board exercises, TRX activates proprioceptors but focuses on dynamic and multi-planar movements [29]. This approach mimics real-world athletic scenarios, making it particularly effective for tasks involving cutting, jumping, or rapid directional changes [16]. The combination of strength, proprioceptive engagement, and functional training contributes to superior improvements in dynamic balance compared to wobble board exercises [16].

Wobble board exercises focus on proprioceptive stimulation and ankle joint stability [13]. By continuously challenging postural control, these exercises enhance the sensory feedback loop between the ankle’s mechanoreceptors and the central nervous system [7]. This leads to improvements in static balance, as evidenced by reduced postural sway and better control during single-leg stance tasks [13]. TRX suspension training combines core stability with dynamic lower-limb strengthening [29]. Its unique approach of integrating multi-planar movements makes it particularly effective for dynamic balance, simulating the demands of athletic activities [17]. Improved core strength and joint control contribute to enhanced dynamic stability [20].

Importantly, the persistent effects observed in both methods six weeks after the post-test stage emphasize their potential for long-term neuromuscular adaptation [30]. This persistence can be attributed to neuroplasticity mechanisms [31]. Neuroplasticity involves long-term potentiation at synapses, enhancing the brain’s ability to process sensory inputs and execute motor outputs [32]. Reflexive control, particularly in the spinal cord, improves with repeated exposure to balance challenges. This results in quicker and more automatic muscle responses to instability, which are retained long-term [33]. Our results showed that in both groups, these adaptations persist even after the cessation of training, as neural pathways remain sensitized to balance-related stimuli. Wobble board and TRX training both effectively improve balance in athletes with functional ankle instability, but their mechanisms of action and persistence differ due to their specific focus areas. The persistent effects of wobble board training are largely attributed to peripheral neuromuscular adaptations [15]. Enhanced proprioceptive sensitivity and joint stabilization mechanisms are retained, reducing the likelihood of instability during sport-specific tasks [15].

TRX training induces both peripheral and central adaptations [34]. Core stability improvements and motor learning associated with multi-planar tasks contribute to sustained dynamic balance. Neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system and spinal cord allow athletes to retain these benefits even after a period of de-training [33]. TRX training’s multi-planar movements may enhance reflex integration across multiple muscle groups, contributing to dynamic stability persistence [34]. Strength gains and hypertrophy in lower-limb and core muscles, achieved through wobble board and TRX training, are maintained for weeks to months post-training due to muscle memory [30]. These structural changes contribute to prolonged functional improvements, particularly in dynamic tasks [34]. Our study found no difference in balance indices between wobble board exercises and TRX exercises. However, TRX exercises may have a greater advantage in improving lower-limb arthrokinematics and overall balance in individuals with functional ankle instability due to their positive effects on core stability muscles.

For athletes with functional ankle instability, rehabilitation strategies could ensure both short-term improvements and long-term persistence in balance performance. Future research should explore the combined use of the wobble board and TRX training to optimize balance rehabilitation strategies. Additionally, longer follow-up periods and diverse athlete populations, including female participants, would enhance the generalizability of findings. One limitation of this study is the absence of direct measurements for proprioception and muscular strength. Future research should incorporate specific assessments, such as joint position sense tests and isokinetic strength evaluations, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of training effects.

Conclusion

Functional training methods significantly enhance balance rehabilitation in athletes with functional ankle instability. Specifically, TRX training and wobble board exercises each target critical components of balance. Implementing these exercises as complementary strategies can provide a holistic approach to addressing both static and dynamic balance deficits. This dual approach not only supports the immediate recovery of balance but also ensures long-term neuromuscular adaptations, equipping athletes to safely return to sport and reduce the risk of re-injury. Coaches and rehabilitation specialists are encouraged to integrate these methods into tailored programs, maximizing their effectiveness in restoring functional stability in athletes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran (Code: ID.UT.SPORT.REC.1397.025). This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration for medical research involving human subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the individuals who participated in the research as subjects.

References

Frequent and chronic lateral ankle ligament sprains can lead to functional ankle instability [1], a condition that is particularly prevalent in athletes who perform dynamic activities, such as jumping and cutting [1]. This injury is the most common type of sports injury, as confirmed by epidemiological studies [2].

Freeman’s hypothesis regarding proprioceptive deficits offers a conceptual basis for comprehending how impairments in sensory feedback contribute to ankle instability [3]. Additionally, further research has demonstrated that delayed muscle activation and diminished muscle strength are key neuromuscular factors that intensify this condition [4, 5]. Functional ankle instability, resulting from a combination of factors, such as proprioception deficits and muscle weakness, can significantly impact balance [4, 5]. Athletes with this condition may struggle to maintain their center of gravity within their base of support, which can affect their performance and increase the risk of injury [6]. Research has consistently found that individuals with functional ankle instability exhibit deficits in both static and dynamic balance, as assessed in both laboratory and field tests [7, 8]. This highlights the direct relationship between ankle instability and balance impairment [6-8]. Given the strong link between balance impairment and recurrent ankle sprains, addressing balance deficits is crucial for individuals with functional ankle instability [9]. Balance impairment has been shown to significantly increase the risk of lower-limb injuries, with individuals experiencing up to five times more injuries compared to those with good balance [9, 10]. This highlights the importance of incorporating balance-enhancing strategies into rehabilitation programs for athletes with functional ankle instability.

Neuromuscular exercises are a valuable tool for rehabilitating balance impairments in individuals with functional ankle instability [11]. These exercises, which target the motor control system, can help improve sensory-motor integration and coordination. Wobble boards are a type of neuromuscular exercise that has gained significant attention in both sports and medical communities in recent decades [12-14]. Although the individual impact of wobble board and TRX training on balance is well-documented, this study distinctively examined their comparative effectiveness and evaluated the sustainability of their benefits after a period of de-training [7, 14, 15]. These exercises are often considered the gold standard for the rehabilitation of this condition [14]. However, more research is needed to understand the long-term benefits of using wobble boards and the importance of persistence in maintaining these exercises.

TRX exercises have emerged as a popular method of strength training in recent years, attracting interest from both athletes and fitness enthusiasts. These exercises are widely used in clinical and sports settings [16, 17]. The ease of use, versatility, and accessibility of TRX exercises make them appealing for people of all ages and fitness levels [18, 19]. These exercises effectively target and activate the core muscles, which is a key benefit for improving overall strength and stability [17]. It has been shown that the core muscles play a crucial role in maintaining balance and proper function of the lower limbs during sports activities [20]. Strength training with TRX has been shown to improve muscle strength and activate proprioceptive receptors, which are crucial for maintaining balance and proper function of the lower limbs during sports activities [21]. While TRX suspension training incorporates a broad range of physical exercises, this study specifically focused on exercises aimed at enhancing proprioception, dynamic balance, and neuromuscular coordination. By concentrating on these targeted exercises, the study provides valuable insights for rehabilitation professionals and sports trainers. Despite the proven effectiveness of both wobble board and TRX training in improving balance, there is a limited number of comparative studies evaluating their relative efficacy in managing functional ankle instability. This research aimed to fill this gap by offering evidence-based recommendations for rehabilitation strategies and assessing the effectiveness of these training interventions on static and dynamic balance indices, including the retention of improvements after a period of de-training.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This quasi-experimental study was performed on 36 male college athletes aged 18-25 with functional ankle instability. To calculate the sample size, G*Power software, version 3.1 was used. Considering the study’s repeated measures ANOVA, a medium overall effect size of f=0.25, an α-error of 0.05, and a desired power (1-ß error) of 0.8, the total sample size resulted in thirty-six participants [22].

The sample consisted of university-level male athletes participating in basketball, volleyball, and handball. These sports require frequent cutting, jumping, and landing movements, which increase the likelihood of ankle sprains. Recruitment focused on these sports to ensure ecological validity for interventions targeting balance rehabilitation in athletes predisposed to ankle instability. Anthropometric data, including age, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI), were collected by the first author before the pre-test assessment, ensuring accuracy and consistency [23].

Participants were included in the study if they met the following criteria: Diagnosed with functional ankle instability; the ability to bear full weight on the affected limb; exhibiting normal gait patterns and complete ankle joint range of motion at the time of participation; a cumberland ankle instability tool (CAIT) score of <27 [24]; and absence of mechanical ankle instability, confirmed through negative anterior drawer and talar tilt tests [13, 23]. Additionally, participants were required to have no history of participating in structured ankle rehabilitation programs within the past six months. Exclusion criteria included the presence of pain that impaired participation in training sessions or assessments, any underlying musculoskeletal or neurological condition affecting lower-limb function, and failure to adhere to the intervention protocol, defined as missing more than two consecutive sessions or three non-consecutive sessions. Eligibility was determined by a licensed physical therapist with over 10 years of clinical experience (second author), who conducted comprehensive evaluations based on the aforementioned criteria. This ensured a consistent and rigorous screening process to recruit participants representative of the target population. While challenges related to managing inactivity periods during follow-up are recognized, these were addressed through regular monitoring and adherence checks to ensure consistency. Before the study, all participants provided written informed consent after being briefed on the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Preparation

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (wobble board training, TRX training, or control) using a computer-generated randomization sequence to minimize allocation bias. Before the pre-test session, all participants were instructed to wear comfortable, athletic clothing suitable for physical activity. Upon arrival, they completed baseline documentation to confirm their eligibility on the testing day. To ensure consistency, a standardized 5-minute warm-up protocol was conducted under the supervision of the first author. This warm-up included dynamic lower-limb exercises, such as controlled leg swings, walking lunges, and ankle mobilization stretches to reduce the risk of injury and prepare the participants for subsequent balance testing. Participants were then familiarized with the testing equipment and procedures, ensuring they understood the requirements and could perform the tasks correctly.

Evaluation of balance indices

Balance indices were measured using the Biodex balance system SD, which quantifies static and dynamic balance on a 12-level adjustable platform. Lower scores indicate better balance performance, reflecting reduced sway and improved stability. The tool was calibrated before each use to ensure reliability [25]. The Biodex balance system was used to conduct the dynamic balance test at level 4 instability. Testing was performed in double-leg stance situation, with the participant standing barefoot in a neutral position. The feet were positioned according to the system’s alignment grid to ensure standardization across all trials. To assess dynamic balance, participants performed a balance test on an unstable platform for 20 seconds in different directions. Each participant performed the test three times, and the average score was recorded. A 30-second break was taken between each repetition. For static balance, the platform was stabilized, and participants performed the same test.

TRX exercise intervention

After completing the pre-test assessments, participants in the experimental groups undertook a structured TRX training program, conducted three times per week over a six-week period on non-consecutive days. To maintain consistency, all training sessions were scheduled at the same time each day. Each session consisted of a standardized 10-minute warm-up, followed by 15–20 minutes of TRX suspension exercises, and concluded with a 5-minute cool-down routine. To ensure proper execution and minimize injury risk, participants completed two familiarization sessions prior to the intervention. The TRX exercise protocol was developed based on established guidelines and peer-reviewed literature on suspension training [26-29]. Exercises targeted major muscle groups and incorporated movements across multiple anatomical planes to simulate functional and sport-specific demands. The training sessions were conducted using the TRX PRO3 suspension trainer system (fitness anywhere LLC, USA), with the equipment securely mounted on a rod 2.5 meters above the ground. Progression in exercise intensity followed the principles of the FITT model (frequency, intensity, time, and type), advancing through five to six difficulty levels. These levels ranged from beginner (levels 1–2) to advanced (levels 5–6), with difficulty adjusted by modifying suspension angles, exercise duration, and dynamic complexity. The progression protocol was carefully designed to ensure a gradual increase in challenge and was validated by a specialist physician [29] (Tables 1 and 2).

The wobble board exercise intervention was conducted over six weeks, with participants completing three sessions per week on non-consecutive days. Each session lasted approximately 30 minutes, starting with a 10-minute warm-up, followed by the main training segment, and concluding with a 5-minute cool-down to promote recovery. To ensure familiarity with the exercises and proper execution, participants underwent two supervised familiarization sessions prior to the intervention. The exercise protocol was adapted from the established methodology of Clark and Burden [12], which has been widely applied in research on functional ankle instability rehabilitation. The protocol focused on progressively challenging static and dynamic balance through controlled movements performed on an unstable surface. The intervention utilized a wobble board with an adjustable tilt angle to tailor difficulty levels as participants advanced through the program. The core training segment (15–20 minutes) involved exercises targeting proprioception, postural control, and neuromuscular adaptation. These exercises included bilateral and unilateral stance tasks, dynamic weight shifts, controlled rotations, and reaching tasks while maintaining stability. Progression followed the principles of the FITT model (frequency, intensity, time, and type), ensuring a gradual increase in challenge by modifying the tilt angle, duration, and complexity of the tasks. For instance, early stages (weeks 1–2) consist of static exercises with a low tilt angle to develop foundational stability, intermediate stages (weeks 3–4) consist of dynamic exercises with an increased tilt angle to challenge dynamic postural control, and advanced stages (weeks 5–6) consist of functional and sport-specific tasks performed with a high tilt angle to simulate real-world balance demands. All sessions were conducted under the supervision of a trained researcher to ensure adherence to proper technique and progression (Table 3).

Participants in the control group were instructed to refrain from engaging in any sports activities throughout the study period and were advised to continue their usual daily routines without modifications. At the end of the training period, balance indices of all subjects were reassessed with the same procedure as the pre-test. Also, in order to assess the persistence of exercises, balance tests were repeated 6 weeks after the post-test.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Subsequently, mixed repeated-measures ANOVA was applied to analyze intergroup comparisons, and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted to assess specific group differences. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 21, with the significance level set at 0.05.

Results

The demographic characteristics of participants showed no significant differences among the three groups, confirming homogeneity at baseline (P>0.05, Table 4). The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the data followed a normal distribution, justifying the use of parametric statistical methods.

The pre-test balance indices, including static and dynamic measures, revealed no significant differences across the three groups in all directions (anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, and overall; P≥0.05). This confirms comparable baseline balance abilities among the groups before the intervention.

The repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated significant improvements in both static and dynamic balance indices for the wobble board and TRX groups in the post-test and follow-up stages compared to the pre-test stage (P≤0.05). Conversely, no significant changes were observed in the control group across any time point (P>0.05). Table 5 presents the comparison of balance indices across the three groups.

The Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated that both wobble board and TRX training significantly outperformed the control group in improving balance indices in all directions during the post-test and follow-up stages (P≤0.05). However, no significant differences were found between the wobble board and TRX groups, suggesting comparable effectiveness of both interventions. The observed effect sizes (eta squared) for balance improvements in the wobble board and TRX groups were moderate to large, reflecting substantial benefits from both interventions. Improvements persisted during the follow-up stage, indicating the retention of training effects six weeks after the post-test stage (Table 6).

Discussion

Our results showed that both wobble board and TRX training programs improved the static and dynamic balance indices in the athletes with functional ankle instability. One possible reason for the improved balance capabilities of the subjects in the present study is the increase in neuromuscular adaptations induced by the training [11]. This study highlights the comparative advantages of wobble board and TRX training for rehabilitating balance in athletes with functional ankle instability. Both methods effectively improve balance, yet their mechanisms and focus differ. Wobble board exercises excel in improving balance by enhancing proprioceptive control at the ankle joint [7]. They are particularly effective in the early stages of rehabilitation, where athletes need to rebuild their stability and reduce postural sway [27]. In contrast, TRX training offers superior dynamic balance improvements due to its integration of core stability, strength, and functional movement patterns [26]. These exercises mimic the demands of athletic performance, making them highly relevant for late-stage rehabilitation and return to sport protocols [7].

Wobble board exercise is a neuromuscular activity designed to improve proprioception and joint stability by challenging balance on an unstable surface [28]. Standing on an unstable surface during wobble board exercises stimulates mechanoreceptors in the ankle joint, such as Ruffini endings, Pacinian corpuscles, and Golgi tendon organs [7]. These receptors detect changes in joint position and movement, sending signals to the central nervous system. Thus, the enhanced proprioceptive feedback improves sensory-motor integration, enabling quicker and more accurate neuromuscular responses to perturbations [11]. By requiring constant adjustments to maintain stability, wobble board exercises engage the stabilizing muscles surrounding the ankle joint [14]. Repeated exposure to unstable conditions enhances the motor control strategies required to maintain balance. This leads to a reduction in postural sway and an improved ability to stabilize the center of gravity over the base of support [15]. The targeted nature of wobble board training on joint proprioception and stabilizer muscle activation makes it particularly effective for balance improvements, especially during single-leg stance tasks [11].

TRX suspension training leverages body weight and gravity as resistance, emphasizing core stability, dynamic strength, and multi-planar movements [29]. TRX exercises uniquely engage core stabilizing muscles (e.g. rectus abdominis, transvers abdominis, obliques, and multifidus) by requiring the athlete to maintain alignment during suspension-based movements [20]. Strong core stability reduces the load on the lower extremities and enhances the kinetic chain’s ability to respond to balance challenges [17]. TRX exercises strengthen lower-limb muscles, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius, through functional movements, like squats, lunges, and planks [26].

These exercises improve dynamic balance by enhancing joint control during sport-specific movements [29]. According to the previous studies, one of the important consequences of functional ankle instability is muscle atrophy and a decrease in the muscle strength of the ankle joint. Therefore, the volume and strength of the lower extremity muscles play a crucial role in determining the displacement and velocity of the center of gravity [29]. By improving lower-limb muscle strength, individuals with functional ankle instability can counteract the muscle weakness that contributes to their condition and enhance their balance [7, 19]. Therefore, it is essential to use exercises that improve the strength of the lower-limb muscles during the rehabilitation of functional ankle instability. Similar to wobble board exercises, TRX activates proprioceptors but focuses on dynamic and multi-planar movements [29]. This approach mimics real-world athletic scenarios, making it particularly effective for tasks involving cutting, jumping, or rapid directional changes [16]. The combination of strength, proprioceptive engagement, and functional training contributes to superior improvements in dynamic balance compared to wobble board exercises [16].

Wobble board exercises focus on proprioceptive stimulation and ankle joint stability [13]. By continuously challenging postural control, these exercises enhance the sensory feedback loop between the ankle’s mechanoreceptors and the central nervous system [7]. This leads to improvements in static balance, as evidenced by reduced postural sway and better control during single-leg stance tasks [13]. TRX suspension training combines core stability with dynamic lower-limb strengthening [29]. Its unique approach of integrating multi-planar movements makes it particularly effective for dynamic balance, simulating the demands of athletic activities [17]. Improved core strength and joint control contribute to enhanced dynamic stability [20].

Importantly, the persistent effects observed in both methods six weeks after the post-test stage emphasize their potential for long-term neuromuscular adaptation [30]. This persistence can be attributed to neuroplasticity mechanisms [31]. Neuroplasticity involves long-term potentiation at synapses, enhancing the brain’s ability to process sensory inputs and execute motor outputs [32]. Reflexive control, particularly in the spinal cord, improves with repeated exposure to balance challenges. This results in quicker and more automatic muscle responses to instability, which are retained long-term [33]. Our results showed that in both groups, these adaptations persist even after the cessation of training, as neural pathways remain sensitized to balance-related stimuli. Wobble board and TRX training both effectively improve balance in athletes with functional ankle instability, but their mechanisms of action and persistence differ due to their specific focus areas. The persistent effects of wobble board training are largely attributed to peripheral neuromuscular adaptations [15]. Enhanced proprioceptive sensitivity and joint stabilization mechanisms are retained, reducing the likelihood of instability during sport-specific tasks [15].

TRX training induces both peripheral and central adaptations [34]. Core stability improvements and motor learning associated with multi-planar tasks contribute to sustained dynamic balance. Neuroplastic changes in the central nervous system and spinal cord allow athletes to retain these benefits even after a period of de-training [33]. TRX training’s multi-planar movements may enhance reflex integration across multiple muscle groups, contributing to dynamic stability persistence [34]. Strength gains and hypertrophy in lower-limb and core muscles, achieved through wobble board and TRX training, are maintained for weeks to months post-training due to muscle memory [30]. These structural changes contribute to prolonged functional improvements, particularly in dynamic tasks [34]. Our study found no difference in balance indices between wobble board exercises and TRX exercises. However, TRX exercises may have a greater advantage in improving lower-limb arthrokinematics and overall balance in individuals with functional ankle instability due to their positive effects on core stability muscles.

For athletes with functional ankle instability, rehabilitation strategies could ensure both short-term improvements and long-term persistence in balance performance. Future research should explore the combined use of the wobble board and TRX training to optimize balance rehabilitation strategies. Additionally, longer follow-up periods and diverse athlete populations, including female participants, would enhance the generalizability of findings. One limitation of this study is the absence of direct measurements for proprioception and muscular strength. Future research should incorporate specific assessments, such as joint position sense tests and isokinetic strength evaluations, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of training effects.

Conclusion

Functional training methods significantly enhance balance rehabilitation in athletes with functional ankle instability. Specifically, TRX training and wobble board exercises each target critical components of balance. Implementing these exercises as complementary strategies can provide a holistic approach to addressing both static and dynamic balance deficits. This dual approach not only supports the immediate recovery of balance but also ensures long-term neuromuscular adaptations, equipping athletes to safely return to sport and reduce the risk of re-injury. Coaches and rehabilitation specialists are encouraged to integrate these methods into tailored programs, maximizing their effectiveness in restoring functional stability in athletes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran (Code: ID.UT.SPORT.REC.1397.025). This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration for medical research involving human subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the individuals who participated in the research as subjects.

References

- Herzog MM, Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Wikstrom EA. Epidemiology of ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Journal of Athletic Training. 2019; 54(6):603-10. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-447-17] [PMID]

- Fransz DP, Huurnink A, Kingma I, de Boode VA, Heyligers IC, van Dieën JH. Performance on a single-legged drop-jump landing test is related to increased risk of lateral ankle sprains among male elite soccer players: A 3-year prospective cohort study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018; 46(14):3454-62. [DOI:10.1177/0363546518808027] [PMID]

- Kim CY, Choi JD. Comparison between ankle proprioception measurements and postural sway test for evaluating ankle instability in subjects with functional ankle instability. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2016; 29(1):97-107. [DOI:10.3233/BMR-150603] [PMID]

- Yu P, Mei Q, Xiang L, Fernandez J, Gu Y. Differences in the locomotion biomechanics and dynamic postural control between individuals with chronic ankle instability and copers: A systematic review. Sports Biomechanics. 2022; 21(4):531-49. [DOI:10.1080/14763141.2021.1954237] [PMID]

- Moisan G, Mainville C, Descarreaux M, Cantin V. Lower limb biomechanics during drop-jump landings on challenging surfaces in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Journal of Athletic Training. 2022; 57(11-12):1039-47. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-0399.21] [PMID]

- Kunugi S, Masunari A, Yoshida N, Miyakawa S. Association between Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool score and postural stability in collegiate soccer players with and without functional ankle instability. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2018; 32:29-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.ptsp.2018.03.002] [PMID]

- Ha SY, Han JH, Sung YH. Effects of ankle strengthening exercise program on an unstable supporting surface on proprioception and balance in adults with functional ankle instability. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2018; 14(2):301-5. [DOI:10.12965/jer.1836082.041] [PMID]

- Hadadi M, Abbasi F. Comparison of the Effect of the Combined Mechanism Ankle Support on Static and Dynamic Postural Control of Chronic Ankle Instability Patients. Foot & Ankle International. 2019; 40(6):702-9. [DOI:10.1177/1071100719833993] [PMID]

- Hung YJ, Boehm J, Reynolds M, Whitehead K, Leland K. Do Single-Leg Balance Control and Lower Extremity Muscle Strength Correlate with Ankle Instability and Leg Injuries in Young Ballet Dancers? Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2021; 25(2):110-6. [DOI:10.12678/1089-313X.061521f] [PMID]

- Šiupšinskas L, Garbenytė-Apolinskienė T, Salatkaitė S, Gudas R, Trumpickas V. Association of pre-season musculoskeletal screening and functional testing with sports injuries in elite female basketball players. Scientific Reports. 2019; 9(1):9286. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-45773-0] [PMID]

- McKeon PO, Wikstrom EA. Sensory-Targeted Ankle Rehabilitation Strategies for Chronic Ankle Instability. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2016; 48(5):776-84. [DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000859] [PMID]

- Clark VM, Burden AM. A 4-week wobble board exercise programme improved muscle onset latency and perceived stability in individuals with a functionally unstable ankle. Physical therapy in Sport. 2005; 6(4):181-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ptsp.2005.08.003]

- Hosseini K, Mohammadian Z, Alimoradi M, Shabani M, Armstrong R, Hogg J, et al. The immediate effect of a balance wobble board protocol on knee and ankle joint position sense in female soccer players. Acta Gymnica. 2023; 53:e2023. [DOI:10.5507/ag.2023.011]

- Wright CJ, Nauman SL, Bosh JC. Wobble-Board Balance Intervention to Decrease Symptoms and Prevent Reinjury in Athletes With Chronic Ankle Instability: An Exploration Case Series. Journal of Athletic Training. 2020; 55(1):42-8. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-346-18] [PMID]

- Linens SW, Ross SE, Arnold BL. Wobble board rehabilitation for improving balance in ankles with chronic instability. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2016; 26(1):76-82. [DOI:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000191] [PMID]

- Andrejeva J, Grisanina A, Sniepienė G, Mockiene A, Strazdauskaite D. The effect of TRX suspension trainer and BOSU platform after reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament of the knee joint. Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sports. 2022; 26(1):47-56. [DOI:10.15561/26649837.2022.0106]

- Iuliana BB, GraŃiela-Flavia DE, Simona MU, Adrian PĂ. TRX suspension training method and static balance in junior basketball players. Educatio Artis Gymnasticae. 2015; 60(3):27-34. [Link]

- Smith LE, Snow J, Fargo JS, Buchanan CA, Dalleck LC. The acute and chronic health benefits of TRX Suspension Training® in healthy adults. International Journal of Research in Exercise Physiology. 2016; 11(2):1-15. [Link]

- Gaedtke A, Morat T. Effects of two 12-week strengthening programmes on functional mobility, strength and balance of older adults: Comparison between TRX suspension training versus an elastic band resistance training. Central European Journal of Sport Sciences and Medicine. 2016; 13(1):49-64. [DOI:10.18276/cej.2016.1-05]

- De Blaiser C, Roosen P, Willems T, Danneels L, Bossche LV, De Ridder R. Is core stability a risk factor for lower extremity injuries in an athletic population? A systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2018; 30:48-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.ptsp.2017.08.076] [PMID]

- Oliva-Lozano JM, Muyor JM. Core muscle activity during physical fitness exercises: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4306. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124306] [PMID]

- Saeterbakken AH, Olsen A, Behm DG, Bardstu HB, Andersen V. The short-and long-term effects of resistance training with different stability requirements. Plos One. 2019; 14(4):e0214302. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0214302] [PMID]

- Gribble PA, Delahunt E, Bleakley C, Caulfield B, Docherty C, Fourchet F, et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: A position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2013; 43(8):585-91. [DOI:10.2519/jospt.2013.0303] [PMID]

- Hadadi M, Ebrahimi Takamjani I, Ebrahim Mosavi M, Aminian G, Fardipour S, Abbasi F. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the Persian version of the Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2017; 39(16):1644-9. [DOI:10.1080/09638288.2016.1207105] [PMID]

- Vallabhajosula S, Freund J, Manning S, Fadool M, Groulx D, Wikstrom EA. P47 Accuracy of athlete single leg test on biodex balance system and y-balance for distinguising individuals with chronic ankle instability. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017; 51(Suppl 1):A31. [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2017-anklesymp.79]

- Janot J, Heltne T, Welles C, Riedl J, Anderson H, Howard A, et al. Effects of TRX versus traditional resistance training programs on measures of muscular performance in adults. Journal of Fitness Research. 2013; 2(2):23-38. [Link]

- Park HS, Oh JK, Kim JY, Yoon JH. The effect of strength and balance training on kinesiophobia, ankle instability, function, and performance in elite adolescent soccer players with functional ankle instability: A prospective cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2024; 23(1):593-602. [DOI:10.52082/jssm.2024.593] [PMID]

- Choi JH, Cynn HS, Baik SM, Kim SH. Effect of foot position on ankle muscle activity during wobble board training in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2024; 47(5-9):134-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.jmpt.2024.09.007] [PMID]

- Khorjahani A, Mirmoezzi M, Bagheri M, Kalantariyan M. Effects of trx suspension training on proprioception and muscle strength in female athletes with functional ankle instability. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021; 12(2):e107042. [DOI:10.5812/asjsm.107042]

- Bakker LB, Nandi T, Lamoth CJ, Hortobágyi T. Task specificity and neural adaptations after balance learning in young adults. Human Movement Science. 2021; 78:102833. [DOI:10.1016/j.humov.2021.102833] [PMID]

- Keller M, Roth R, Achermann S, Faude O. Learning a new balance task: The influence of prior motor practice on training adaptations. European Journal of Sport Science. 2023; 23(5):809-17. [DOI:10.1080/17461391.2022.2053751] [PMID]

- Mansour AR, Farmer MA, Baliki MN, Apkarian AV. Chronic pain: The role of learning and brain plasticity. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2014; 32(1):129-39. [DOI:10.3233/RNN-139003] [PMID]

- Ostry DJ, Gribble PL. Sensory plasticity in human motor learning. Trends in Neurosciences. 2016; 39(2):114-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.tins.2015.12.006] [PMID]

- Ghahfarrokhi MM, Shirvani H, Rahimi M, Bazgir B, Shamsadini A, Sobhani V. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of different intensities of functional training in elderly type 2 diabetes patients with cognitive impairment: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics. 2024; 24(1):71. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-024-04698-8] [PMID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Sport injury and corrective exercises

Received: 2024/09/25 | Accepted: 2025/01/26 | Published: 2026/01/1

Received: 2024/09/25 | Accepted: 2025/01/26 | Published: 2026/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |