Fri, Oct 10, 2025

Volume 14, Issue 4 (Autumn 2024)

PTJ 2024, 14(4): 291-302 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jalili Bafrouei M, Seyedi M, Mirkarimpour S H. Validity, Reliability, and Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Persian (Farsi) Version of Profile Fitness Mapping Back Questionnaire. PTJ 2024; 14 (4) :291-302

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-638-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-638-en.html

1- Department of Sport Injuries and Biomechanics, Faculty of Sport Sciences and Health, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Sports Medicine, Sports Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Sports Sciences, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shomal University, Amol, Iran.

2- Department of Sports Medicine, Sports Sciences Research Institute, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Sports Sciences, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shomal University, Amol, Iran.

Keywords: Functional limitation, Low back pain (LBP), Pro-fit-map, questionnaire, Validity, Reliability

Full-Text [PDF 564 kb]

(596 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1722 Views)

Full-Text: (405 Views)

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition that causes discomfort and imposes a heavy treatment burden on medical services and society [1]. Evaluating and documenting a person’s pain, other symptoms caused by back pain, and functional status is essential in understanding its impact on their lives. It is critical to have approved and valid criteria to measure pain and functional limitations in clinical evaluation and services [2, 3]. Pain is a crucial factor that, if not adequately assessed, can negatively impact health outcomes and is often wrongly associated with physical performance [4, 5]. Pain and other symptoms related to the core of the body warrant investigation. One weakness of pain assessment is the lack of information regarding the pain’s frequency and duration [6]. The evidence indicates that measuring pain frequency is valid and provides dimension to pain intensity [7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed an International classification of functioning (ICF), disability, and overall health of individuals. This system is known as the biological-psychological model of disability and categorizes health into three main areas physical, personal, and social [8]. ICF is one of the available methods for dividing questionnaire content [9]. Questionnaires designed to evaluate the functional status of individuals with LBP typically consist of two parts, assessing pain and physical performance [3, 9]. These questionnaires fall under the ICF framework, specifically functional impairment relating to physical aspects and movement limitations. Furthermore, this category is associated with the personal aspect [3]. Some individuals who experience LBP may reduce their activity levels. Their treatment may increase activity levels and performance while relieving back pain [5]. However, some individuals may only experience increased pain while maintaining their activity level at the pre-back pain stage. Their treatment should solely aim to reduce pain while increasing limited function [9]. Therefore, the questionnaires aim to address all concerns related to symptoms and functional limitations caused by back pain during the assessment. Extracting scores from pain and physical function limitations cannot accurately represent a person’s limitations because they may be better in some areas and worse in others. Therefore, scoring and evaluation cannot lead to success because the main factor cannot be accurately evaluated [10]. The validity and reliability of the profile fitness mapping (PFM) questionnaire have been compared and checked with four specialized questionnaires, including the Aberdeen LBP disability scale, the Waddell disability index, the low back outcome score [11], and the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire [12], as well as a general questionnaire, the short form health survey SF [13]. The results indicate that the PFM questionnaire has high validity and reliability, mainly when used with these four specialized questionnaires. The final result of each index is expressed as a percentage, with 100% representing the best possible state.

It is essential to consider the placement of specific questionnaires to determine whether pain or movement limitation is the dominant problem. This study aims to assess the extent of symptoms and functional limitations in people, including their severity and duration. When conducting research in the Middle East, especially in Iran, it is essential to consider the diverse lifestyles and bio-cultural differences present in the region. This involves comprehending the social behaviors and religious customs concerning cleanliness and hygiene. Hence, it is crucial to meticulously revise and customize international questionnaires to harmonize with the particular norms and practices of the host country. Thus this study aims to evaluate the reliability and validity of a new questionnaire for mapping physical fitness in the lower back area and also, and cultural adaptation has been considered. The intended recipients of this questionnaire are individuals who suffer from chronic back pain.

Materials and Methods

Questionnaire translation process

The PFM questionnaire in the lower back area was translated from English to Persian using the guidelines recommended by the international quality of life assessment group [14]. In the first stage, two native Persian speakers separately translated the original English questionnaire into Persian. After arguing about differences in a meeting, they then agreed on a unified version. Two Persian bilingual translators translated the same version to English and corrected any errors (if needed). The final version was piloted among 53 Persian-speaking individuals with chronic back pain to identify complex or incomprehensible items or answers.

Two methods were used to determine content validity, content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). Eight experts in corrective exercise and sports injuries, who were university teachers, were asked to choose one of three options to determine the CVR, necessary, helpful but not necessary, and necessary for each question or item. According to Lawshe’s table [15, 16], if the score obtained for each question is more significant than 0.75 (based on evaluations from eight experts), it suggests that the question is essential to include in the tool with an acceptable level of significance. Eight experts were asked to evaluate each question’s CVI, relevance, clarity, simplicity, and ambiguity using a 4-point Likert scale. One way to assess the relationship between two items is to use a scale of 1 to 4. The options are no relation, somewhat related, good relation, and very high relation. CVI was calculated as the percentage of items with agreeable points (ranks 3 and 4) among total voters. The CVI score required for item acceptance was higher than 0.79 [17].

Research inclusion and exclusion criteria

Fifty-three people with a history of chronic back pain completed the questionnaire at Arvand Physiotherapy Clinic in Tehran City, Iran. The inclusion criteria included individuals who were diagnosed with chronic back pain by a physician and underwent physical and orthopedic examinations and were considered eligible for the study. The study focused specifically on individuals who experienced pain exclusively in their lower back [18] and had experienced this pain for over a year, when at rest or stretching their back. The exclusion criteria included various conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, connective tissue diseases, infectious diseases, lumbar disc conditions, spinal canal stenosis, and vertebral dislocation [19]. After applying the selection criteria, 58 individuals were chosen to assess the questionnaire’s validity and reliability.

Test re-test reliability of the Persian profile fitness mapping (PFM) questionnaire

The PFM back pain questionnaire is a sensitive and reliable tool for recording the pain and movement limitations of people with chronic back pain [20]. This questionnaire is based on 26 key questions of the symptom scale, 29 key questions of functional limitation (Appendix), and a score that differentiates between the severity, duration of pain, and functional limitation of people with LBP.

Fifty-eight participants were asked to complete questionnaires to assess the test’s reliability. Out of the 58 questionnaires that were given to athletes, 53 were returned, giving a response rate of 93%. As the back pain questionnaire is designed for individuals with chronic back pain, the research participants were purposefully and homogeneously selected. Participants were selected via convenience sampling and provided written consent to participate. The participants completed the questionnaire once again after two weeks. The people who did not complete the questionnaire at the appointed time were reminded by phone. Those who still needed to complete the second questionnaire (re-test) were removed from the review process.

Symptom scale

The PFM symptom scale consists of 27 questions and measures the severity and duration of symptoms. The symptoms are assessed in two aspects, intensity and time. Therefore, each question in this section has a two-part answer. Each of the 27 questions in the survey is assigned a numerical value ranging from 1 to 6 based on the duration of symptoms and 7 to 12 based on the severity of symptoms. The total score of scale determines ranges for the duration`of symptoms and the severity of symptoms between 27 to 162 and 189 to 324, respectively. For each question, the numerical values of the answers range from 1 to 12. The scale is as follows: 1 represents “never,” 2 for “rarely,” 3 for “very little,” 4 for “sometimes,” 5 for “often,” 6 for “always” or “most of the time” of the symptoms, 7 for “not at all” or “none,” 8 for “little” or “weakly,” 9 for “moderately low” or “moderately weak,” 10 is “moderately high,” 11 is “high,” and 12 is “very high” and “intolerable” for the severity of symptoms. Higher scores indicate greater injury severity [3].

Functional limitation scale

The 28-question PFM functional limitation scale was used to evaluate functional limitations in daily activities caused by chronic back pain. The answer to each of these 28 questions is assigned a numerical value between 1 and 6, and the sum of these values determines the person’s functional limitation score between 28 and 168. The answers to the questions are rated based on a six-point scale to provide a comprehensive evaluation. The scale ranges from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating that the response is very good and there are no issues to report, 2 representing a good response, and a score of 3 indicating a pretty good response. A rating of 4 suggests that the response was inadequate, while a score of 5 indicates a poor response. Finally, a score of 6 indicates that the response was feeble. The higher the points obtained, the more functional limitations caused by chronic back pain in performing daily activities [3].

Statistical test

SPSS software, version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used to analyze data. Tests to evaluate people in clinical settings should be highly reliable and acceptable [21]. With a statistical power of 80%, an expected reliability of 90%, and a significance level of 0.05, the necessary sample size for the research included 49 participants. Then, Cronbach’s α was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the questions. In such a way, zero indicates no internal homogeneity, and one indicates complete internal homogeneity. Since this questionnaire allows people to specify the type of their health problem in terms of different degrees of severity, time of pain, and functional limitation, people may choose a different option for the first time than the re-test or vice versa. Data on test re-test reliability is referred to Table 1.

Results

Translating and localizing the questionnaire

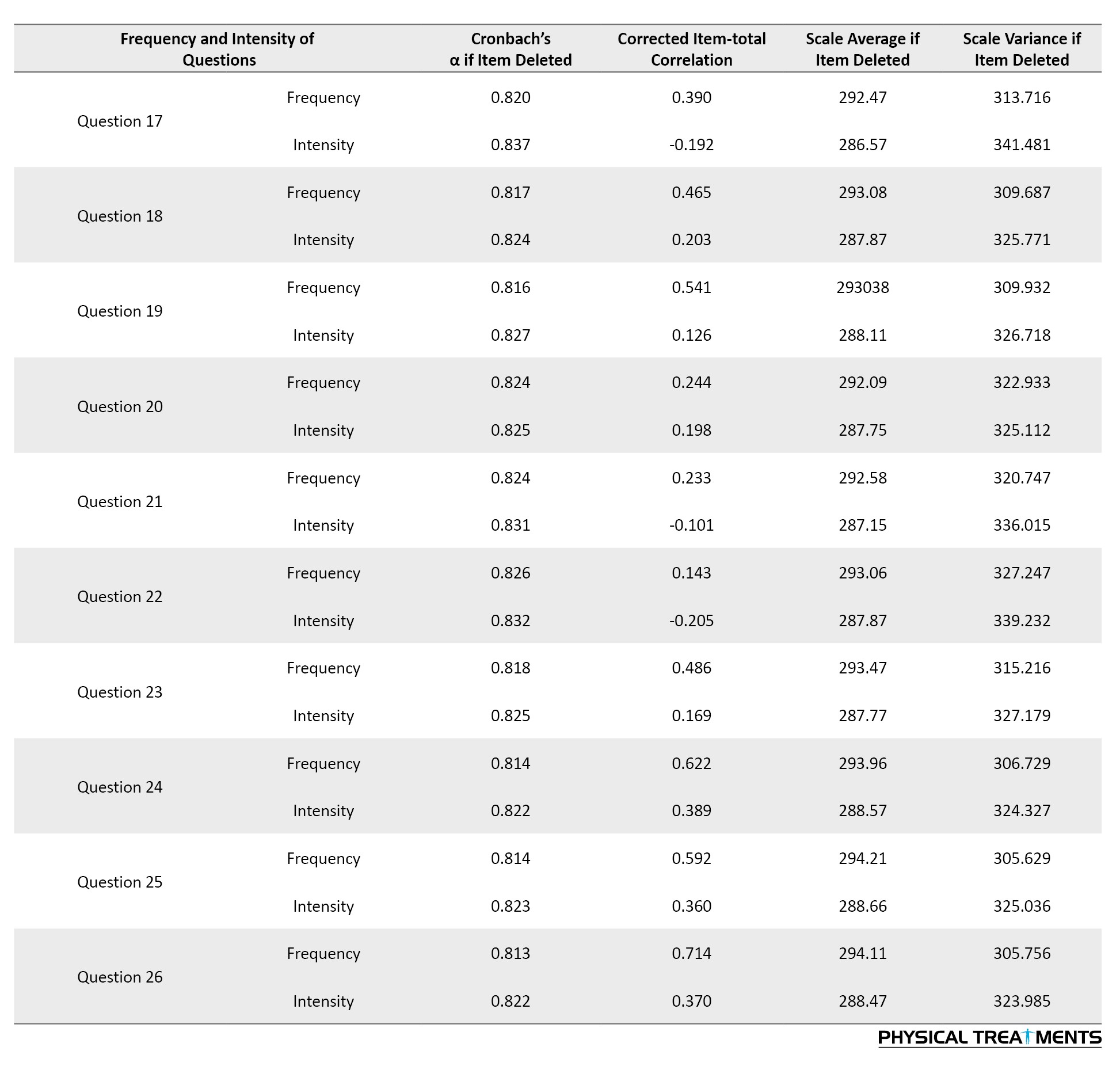

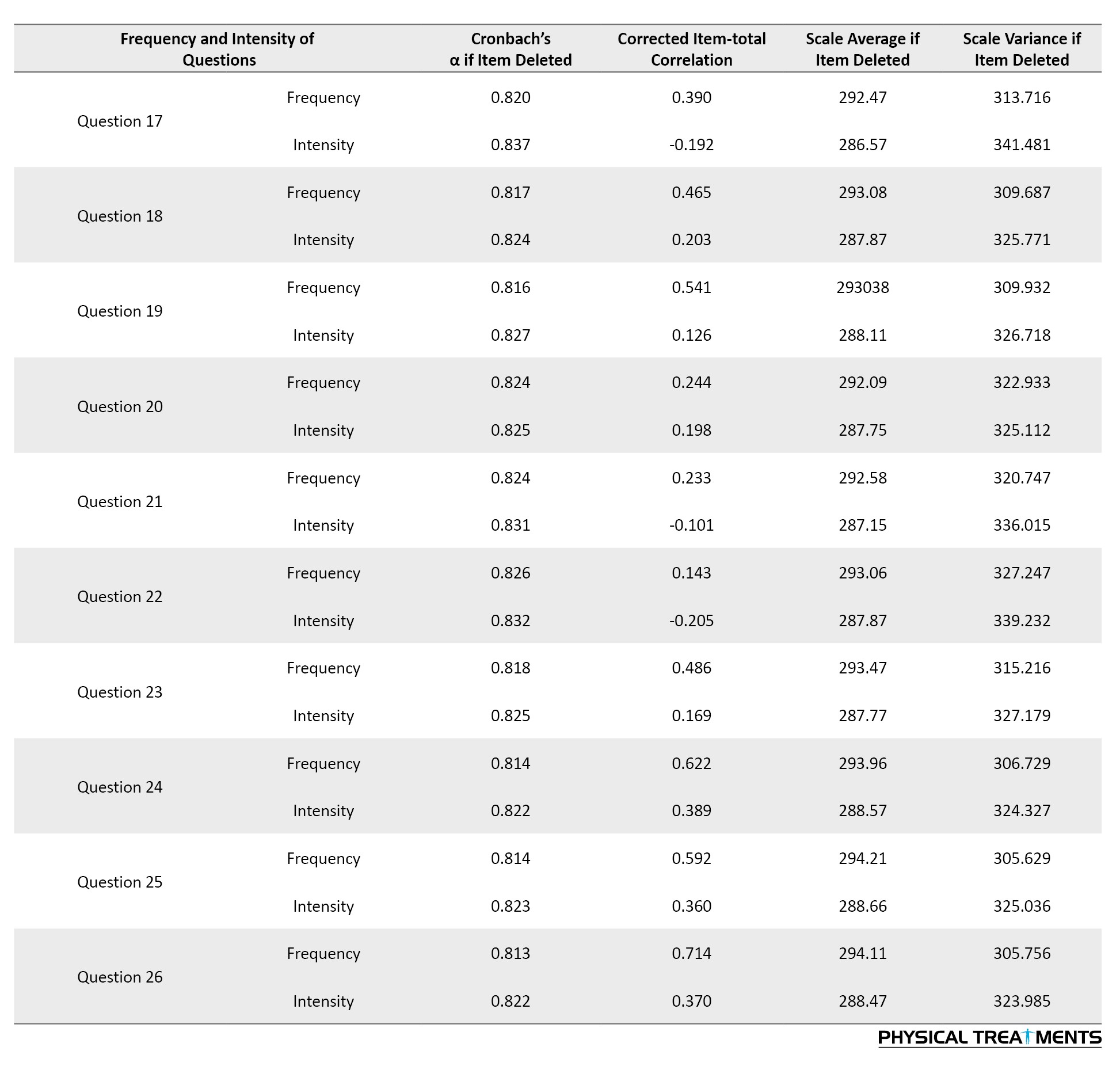

No significant differences were found between the English-translated questionnaire and the original. Only minor differences in synonyms were detected in some cases. For instance, ‘emptying the bowls’ was translated as ‘defecation.’ Due to confusion regarding “dryness” in question 1, replace “dryness and stiffness” and, in question 4, replace “tension” with “tension and tightness.” According to the values obtained from the content ratio analysis, question 9’s significance level was lower than the minimum (CVR value of 0.50), therefore it was removed from the final form of the translation. The obtained numbers for other questionnaire questions had an acceptable significance level (0.75-1). It is worth mentioning that the questionnaire’s average CVI (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.93. Statistical analysis revealed that the symptom scale and functional limitation questionnaire had high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.91 and 0.95, respectively. Table 2 shows the impact of removing items on the internal consistency and correlation of the modified total item for the symptom scale.

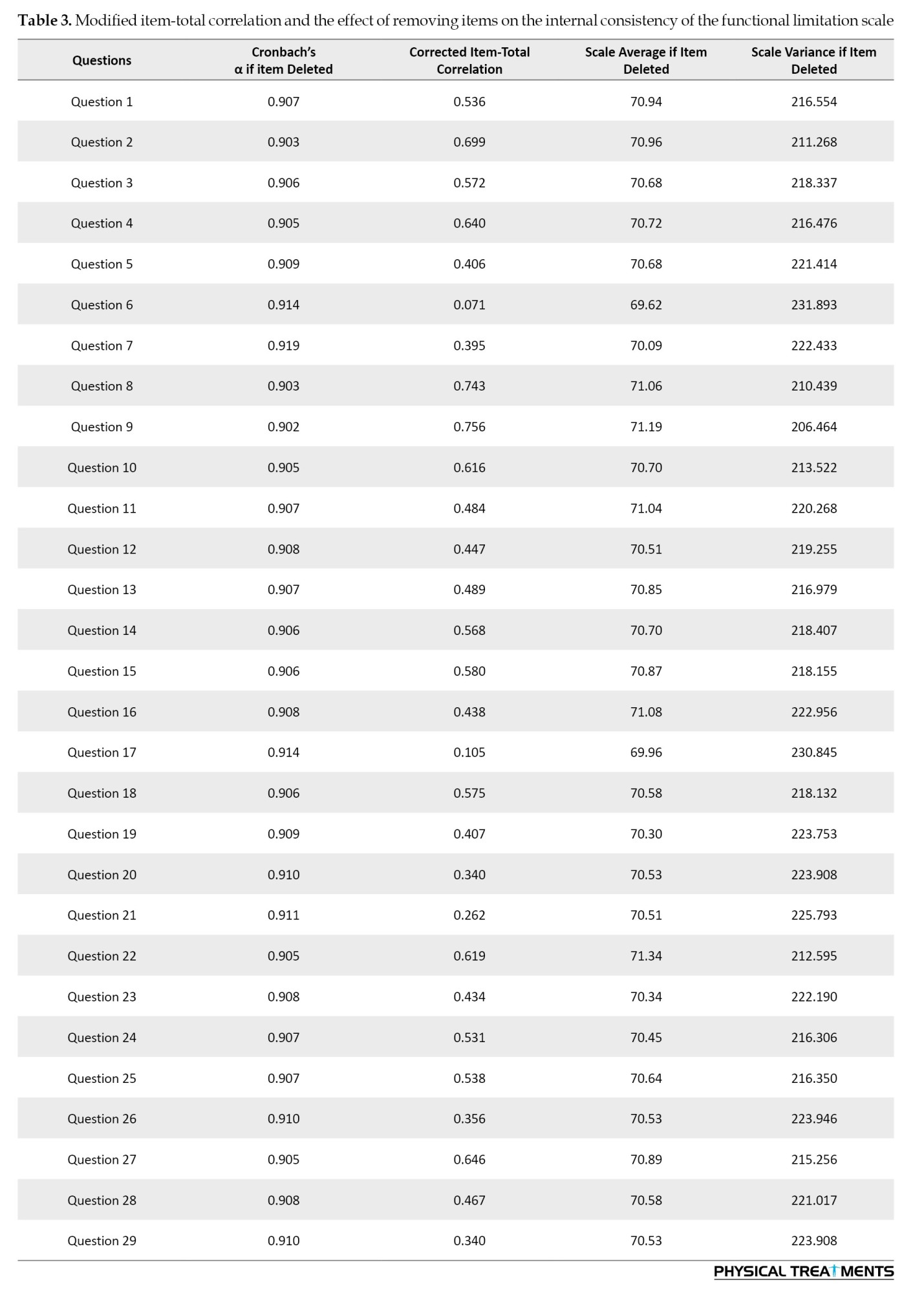

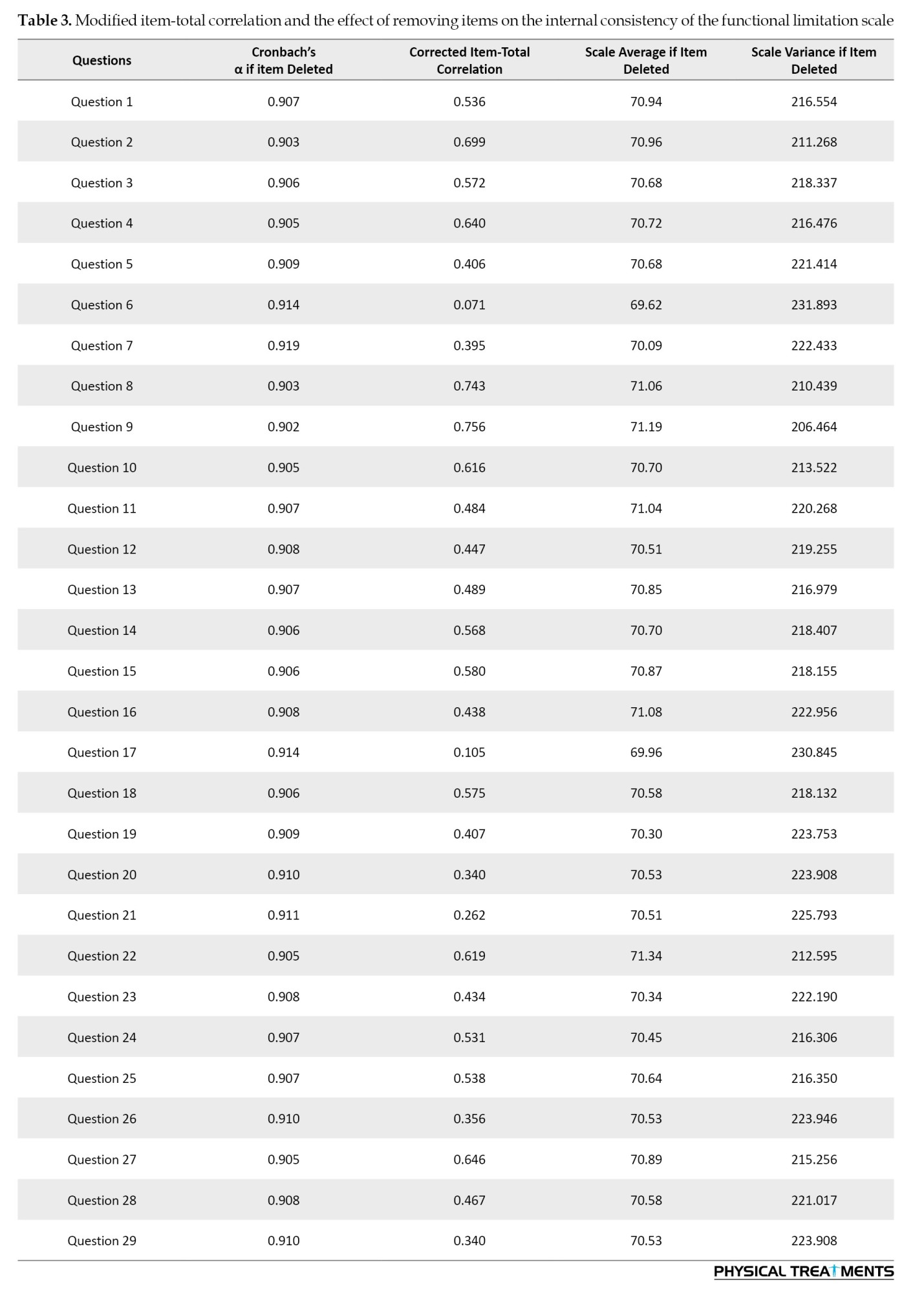

In contrast, Table 3 presents the same functional limitation.

The reliability test aims to distinguish fundamental differences in scores from random measurement errors [22]. Hence, Table 3 displays the reliability of all questions during the test re-test for each question.

Discussion

Our study was conducted to translate and cross-cultural adapt the questionnaire on physical fitness mapping in Persian and assess its reliability and validity. During a review study, Wallwork et al. showed that people with acute and sub-acute pain in the lower back may recover after six weeks. However, there may be continuous pain and limited movement in the back. Hence, people who have 12 weeks or more have moderate to high persistent back pain, and functional limitations and pain, therefore identifying these people should be a priority for interventions [23]. Pierobon and Darlow, reported that the back pain questionnaire is valuable for the general population, people with certain diseases, and even athletes with back pain. It can also be used for clinical evaluations [24]. O’Hagan et al. surveyed 313 people. They concluded that using the back pain questionnaire has led to more people’s satisfaction, and their treatment and recovery process has increased significantly [25]. Fifty-three people participated in this research; 31 were men, and 22 were women.

The PFM questionnaire is the first to cover pain intensity and frequency symptoms simultaneously as a functional limitation and provides the ability to record and distinguish between these concepts among people. According to experts, question 9 of the symptom scale questionnaire, “have you had a cramping feeling in the back?” due to the similarity to the previous questions in the questionnaire and the same general meaning and concept, this question was not considered necessary in the questionnaire, and this question was removed from the final form. Therefore, the final version of the Persian PFM symptom scale questionnaire with 26 questions was presented. Also, in the functional limitation scale, the question “How do you sit on the toilet stone despite back pain?” was added according to experts’ opinions to receive more comprehensive information about people’s essential needs. Therefore, the final second part of the Persian questionnaire on the functional limitation scale in the lumbar region was presented with 29 questions.

In this research, several factors can affect the test re-test reliability. One of these factors is the time interval between the test and the re-test, which was determined to be ten days in the current research. A time interval between 2 and 14 days between the test and re-test is recommended [26]. Shorter time intervals increase reliability because participants remember the answers more quickly. On the other hand, long time intervals provide the possibility of changes in the intensity and frequency of back pain and functional limitation, thus causing the reliability of the questionnaire to be estimated as lower than its actual value. The statistical test showed good to excellent reliability between the test re-test scores in the two scales of symptoms and functional limitations, which are presented in Table 3. Also, the lack of significant difference between the test re-test scores confirms this questionnaire’s desirable and acceptable reliability.

Some participants in this study changed their scores during the test re-test. It indicates the fluctuation between the time intervals according to the person’s activity and performance. Also, a more suitable method for recording this back pain has not been provided until now. However, despite limitations in determining the type of problem, the present method records the consequences well to a large extent. The questionnaire has good internal consistency, similar to the original English version. Based on Tables 2 and 3, removing items does not improve the overall Cronbach’s α. It indicates that each question contributes equally to the measured factor. The effectiveness of this method of collecting data largely relies on the number of people who respond to it. In the current study, the average response rate of people answered the PFM questionnaire was 93%, which is desirable and high. This high response rate helps to reduce the possibility of response bias during the test re-test [24]. While the high rate is currently being maintained, it may not be sustainable in the long run. However, motivating people to participate could help address this issue. On average, people took 7 minutes (5.8-5.6) to complete the questionnaire.

This questionnaire has limitations. Information on back pain should be narrower based on people’s reports and definitions. Many cases of reported back pain may only occur after physical activity. The solution to this problem is immediately confirming issues reported by people with medical evaluation, increasing research difficulty and costs.

The accuracy of the questionnaire is contingent on individuals providing truthful responses. However, some may feel hesitant to report symptoms or motor disabilities as they fear it could negatively impact their ability to carry out the daily activities that they enjoy. In such cases, the authenticity of the responses may be questioned. People should be assured that their answers will be used confidentially and only for research to reduce risk. Each questionnaire can include this explanation in a note or writing. Another limitation of using the PFM questionnaire is that only information about the lumbar region is recorded, and the type of injury or its exact diagnosis is not determined. Of course, this information is accessible based on clinical assessment, and it seems people cannot provide it accurately. However, in future studies, the degree of agreement between the results of people’s self-assessments and the doctor’s diagnosis of the type of problem should be investigated.

A practical tool for monitoring health has been translated and published to prevent the emergence of different versions and allow for comparison of research findings conducted in various countries. The PFM questionnaire has been translated into Persian using standard methods, and cultural contexts have been considered. Its validity and reliability have been confirmed for use among Persian-speaking people. In future studies, the PFM questionnaire can be administered electronically via mobile apps, saving time and streamlining data collection and processing. Based on the current research results, the physical fitness mapping questionnaire for the lower back region has introduced a new method for accurately recording the types of back pain problems people face. This method is reliable and valid in monitoring and recording the symptoms and functional limitations caused by back pain.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations regarding research and the protection of individuals’ privacy have been strictly adhered to in the conduct of this study for the article.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contribute to preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants who contributed to the study.

References

Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition that causes discomfort and imposes a heavy treatment burden on medical services and society [1]. Evaluating and documenting a person’s pain, other symptoms caused by back pain, and functional status is essential in understanding its impact on their lives. It is critical to have approved and valid criteria to measure pain and functional limitations in clinical evaluation and services [2, 3]. Pain is a crucial factor that, if not adequately assessed, can negatively impact health outcomes and is often wrongly associated with physical performance [4, 5]. Pain and other symptoms related to the core of the body warrant investigation. One weakness of pain assessment is the lack of information regarding the pain’s frequency and duration [6]. The evidence indicates that measuring pain frequency is valid and provides dimension to pain intensity [7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed an International classification of functioning (ICF), disability, and overall health of individuals. This system is known as the biological-psychological model of disability and categorizes health into three main areas physical, personal, and social [8]. ICF is one of the available methods for dividing questionnaire content [9]. Questionnaires designed to evaluate the functional status of individuals with LBP typically consist of two parts, assessing pain and physical performance [3, 9]. These questionnaires fall under the ICF framework, specifically functional impairment relating to physical aspects and movement limitations. Furthermore, this category is associated with the personal aspect [3]. Some individuals who experience LBP may reduce their activity levels. Their treatment may increase activity levels and performance while relieving back pain [5]. However, some individuals may only experience increased pain while maintaining their activity level at the pre-back pain stage. Their treatment should solely aim to reduce pain while increasing limited function [9]. Therefore, the questionnaires aim to address all concerns related to symptoms and functional limitations caused by back pain during the assessment. Extracting scores from pain and physical function limitations cannot accurately represent a person’s limitations because they may be better in some areas and worse in others. Therefore, scoring and evaluation cannot lead to success because the main factor cannot be accurately evaluated [10]. The validity and reliability of the profile fitness mapping (PFM) questionnaire have been compared and checked with four specialized questionnaires, including the Aberdeen LBP disability scale, the Waddell disability index, the low back outcome score [11], and the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire [12], as well as a general questionnaire, the short form health survey SF [13]. The results indicate that the PFM questionnaire has high validity and reliability, mainly when used with these four specialized questionnaires. The final result of each index is expressed as a percentage, with 100% representing the best possible state.

It is essential to consider the placement of specific questionnaires to determine whether pain or movement limitation is the dominant problem. This study aims to assess the extent of symptoms and functional limitations in people, including their severity and duration. When conducting research in the Middle East, especially in Iran, it is essential to consider the diverse lifestyles and bio-cultural differences present in the region. This involves comprehending the social behaviors and religious customs concerning cleanliness and hygiene. Hence, it is crucial to meticulously revise and customize international questionnaires to harmonize with the particular norms and practices of the host country. Thus this study aims to evaluate the reliability and validity of a new questionnaire for mapping physical fitness in the lower back area and also, and cultural adaptation has been considered. The intended recipients of this questionnaire are individuals who suffer from chronic back pain.

Materials and Methods

Questionnaire translation process

The PFM questionnaire in the lower back area was translated from English to Persian using the guidelines recommended by the international quality of life assessment group [14]. In the first stage, two native Persian speakers separately translated the original English questionnaire into Persian. After arguing about differences in a meeting, they then agreed on a unified version. Two Persian bilingual translators translated the same version to English and corrected any errors (if needed). The final version was piloted among 53 Persian-speaking individuals with chronic back pain to identify complex or incomprehensible items or answers.

Two methods were used to determine content validity, content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). Eight experts in corrective exercise and sports injuries, who were university teachers, were asked to choose one of three options to determine the CVR, necessary, helpful but not necessary, and necessary for each question or item. According to Lawshe’s table [15, 16], if the score obtained for each question is more significant than 0.75 (based on evaluations from eight experts), it suggests that the question is essential to include in the tool with an acceptable level of significance. Eight experts were asked to evaluate each question’s CVI, relevance, clarity, simplicity, and ambiguity using a 4-point Likert scale. One way to assess the relationship between two items is to use a scale of 1 to 4. The options are no relation, somewhat related, good relation, and very high relation. CVI was calculated as the percentage of items with agreeable points (ranks 3 and 4) among total voters. The CVI score required for item acceptance was higher than 0.79 [17].

Research inclusion and exclusion criteria

Fifty-three people with a history of chronic back pain completed the questionnaire at Arvand Physiotherapy Clinic in Tehran City, Iran. The inclusion criteria included individuals who were diagnosed with chronic back pain by a physician and underwent physical and orthopedic examinations and were considered eligible for the study. The study focused specifically on individuals who experienced pain exclusively in their lower back [18] and had experienced this pain for over a year, when at rest or stretching their back. The exclusion criteria included various conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, connective tissue diseases, infectious diseases, lumbar disc conditions, spinal canal stenosis, and vertebral dislocation [19]. After applying the selection criteria, 58 individuals were chosen to assess the questionnaire’s validity and reliability.

Test re-test reliability of the Persian profile fitness mapping (PFM) questionnaire

The PFM back pain questionnaire is a sensitive and reliable tool for recording the pain and movement limitations of people with chronic back pain [20]. This questionnaire is based on 26 key questions of the symptom scale, 29 key questions of functional limitation (Appendix), and a score that differentiates between the severity, duration of pain, and functional limitation of people with LBP.

Fifty-eight participants were asked to complete questionnaires to assess the test’s reliability. Out of the 58 questionnaires that were given to athletes, 53 were returned, giving a response rate of 93%. As the back pain questionnaire is designed for individuals with chronic back pain, the research participants were purposefully and homogeneously selected. Participants were selected via convenience sampling and provided written consent to participate. The participants completed the questionnaire once again after two weeks. The people who did not complete the questionnaire at the appointed time were reminded by phone. Those who still needed to complete the second questionnaire (re-test) were removed from the review process.

Symptom scale

The PFM symptom scale consists of 27 questions and measures the severity and duration of symptoms. The symptoms are assessed in two aspects, intensity and time. Therefore, each question in this section has a two-part answer. Each of the 27 questions in the survey is assigned a numerical value ranging from 1 to 6 based on the duration of symptoms and 7 to 12 based on the severity of symptoms. The total score of scale determines ranges for the duration`of symptoms and the severity of symptoms between 27 to 162 and 189 to 324, respectively. For each question, the numerical values of the answers range from 1 to 12. The scale is as follows: 1 represents “never,” 2 for “rarely,” 3 for “very little,” 4 for “sometimes,” 5 for “often,” 6 for “always” or “most of the time” of the symptoms, 7 for “not at all” or “none,” 8 for “little” or “weakly,” 9 for “moderately low” or “moderately weak,” 10 is “moderately high,” 11 is “high,” and 12 is “very high” and “intolerable” for the severity of symptoms. Higher scores indicate greater injury severity [3].

Functional limitation scale

The 28-question PFM functional limitation scale was used to evaluate functional limitations in daily activities caused by chronic back pain. The answer to each of these 28 questions is assigned a numerical value between 1 and 6, and the sum of these values determines the person’s functional limitation score between 28 and 168. The answers to the questions are rated based on a six-point scale to provide a comprehensive evaluation. The scale ranges from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating that the response is very good and there are no issues to report, 2 representing a good response, and a score of 3 indicating a pretty good response. A rating of 4 suggests that the response was inadequate, while a score of 5 indicates a poor response. Finally, a score of 6 indicates that the response was feeble. The higher the points obtained, the more functional limitations caused by chronic back pain in performing daily activities [3].

Statistical test

SPSS software, version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used to analyze data. Tests to evaluate people in clinical settings should be highly reliable and acceptable [21]. With a statistical power of 80%, an expected reliability of 90%, and a significance level of 0.05, the necessary sample size for the research included 49 participants. Then, Cronbach’s α was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the questions. In such a way, zero indicates no internal homogeneity, and one indicates complete internal homogeneity. Since this questionnaire allows people to specify the type of their health problem in terms of different degrees of severity, time of pain, and functional limitation, people may choose a different option for the first time than the re-test or vice versa. Data on test re-test reliability is referred to Table 1.

Results

Translating and localizing the questionnaire

No significant differences were found between the English-translated questionnaire and the original. Only minor differences in synonyms were detected in some cases. For instance, ‘emptying the bowls’ was translated as ‘defecation.’ Due to confusion regarding “dryness” in question 1, replace “dryness and stiffness” and, in question 4, replace “tension” with “tension and tightness.” According to the values obtained from the content ratio analysis, question 9’s significance level was lower than the minimum (CVR value of 0.50), therefore it was removed from the final form of the translation. The obtained numbers for other questionnaire questions had an acceptable significance level (0.75-1). It is worth mentioning that the questionnaire’s average CVI (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.93. Statistical analysis revealed that the symptom scale and functional limitation questionnaire had high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.91 and 0.95, respectively. Table 2 shows the impact of removing items on the internal consistency and correlation of the modified total item for the symptom scale.

In contrast, Table 3 presents the same functional limitation.

The reliability test aims to distinguish fundamental differences in scores from random measurement errors [22]. Hence, Table 3 displays the reliability of all questions during the test re-test for each question.

Discussion

Our study was conducted to translate and cross-cultural adapt the questionnaire on physical fitness mapping in Persian and assess its reliability and validity. During a review study, Wallwork et al. showed that people with acute and sub-acute pain in the lower back may recover after six weeks. However, there may be continuous pain and limited movement in the back. Hence, people who have 12 weeks or more have moderate to high persistent back pain, and functional limitations and pain, therefore identifying these people should be a priority for interventions [23]. Pierobon and Darlow, reported that the back pain questionnaire is valuable for the general population, people with certain diseases, and even athletes with back pain. It can also be used for clinical evaluations [24]. O’Hagan et al. surveyed 313 people. They concluded that using the back pain questionnaire has led to more people’s satisfaction, and their treatment and recovery process has increased significantly [25]. Fifty-three people participated in this research; 31 were men, and 22 were women.

The PFM questionnaire is the first to cover pain intensity and frequency symptoms simultaneously as a functional limitation and provides the ability to record and distinguish between these concepts among people. According to experts, question 9 of the symptom scale questionnaire, “have you had a cramping feeling in the back?” due to the similarity to the previous questions in the questionnaire and the same general meaning and concept, this question was not considered necessary in the questionnaire, and this question was removed from the final form. Therefore, the final version of the Persian PFM symptom scale questionnaire with 26 questions was presented. Also, in the functional limitation scale, the question “How do you sit on the toilet stone despite back pain?” was added according to experts’ opinions to receive more comprehensive information about people’s essential needs. Therefore, the final second part of the Persian questionnaire on the functional limitation scale in the lumbar region was presented with 29 questions.

In this research, several factors can affect the test re-test reliability. One of these factors is the time interval between the test and the re-test, which was determined to be ten days in the current research. A time interval between 2 and 14 days between the test and re-test is recommended [26]. Shorter time intervals increase reliability because participants remember the answers more quickly. On the other hand, long time intervals provide the possibility of changes in the intensity and frequency of back pain and functional limitation, thus causing the reliability of the questionnaire to be estimated as lower than its actual value. The statistical test showed good to excellent reliability between the test re-test scores in the two scales of symptoms and functional limitations, which are presented in Table 3. Also, the lack of significant difference between the test re-test scores confirms this questionnaire’s desirable and acceptable reliability.

Some participants in this study changed their scores during the test re-test. It indicates the fluctuation between the time intervals according to the person’s activity and performance. Also, a more suitable method for recording this back pain has not been provided until now. However, despite limitations in determining the type of problem, the present method records the consequences well to a large extent. The questionnaire has good internal consistency, similar to the original English version. Based on Tables 2 and 3, removing items does not improve the overall Cronbach’s α. It indicates that each question contributes equally to the measured factor. The effectiveness of this method of collecting data largely relies on the number of people who respond to it. In the current study, the average response rate of people answered the PFM questionnaire was 93%, which is desirable and high. This high response rate helps to reduce the possibility of response bias during the test re-test [24]. While the high rate is currently being maintained, it may not be sustainable in the long run. However, motivating people to participate could help address this issue. On average, people took 7 minutes (5.8-5.6) to complete the questionnaire.

This questionnaire has limitations. Information on back pain should be narrower based on people’s reports and definitions. Many cases of reported back pain may only occur after physical activity. The solution to this problem is immediately confirming issues reported by people with medical evaluation, increasing research difficulty and costs.

The accuracy of the questionnaire is contingent on individuals providing truthful responses. However, some may feel hesitant to report symptoms or motor disabilities as they fear it could negatively impact their ability to carry out the daily activities that they enjoy. In such cases, the authenticity of the responses may be questioned. People should be assured that their answers will be used confidentially and only for research to reduce risk. Each questionnaire can include this explanation in a note or writing. Another limitation of using the PFM questionnaire is that only information about the lumbar region is recorded, and the type of injury or its exact diagnosis is not determined. Of course, this information is accessible based on clinical assessment, and it seems people cannot provide it accurately. However, in future studies, the degree of agreement between the results of people’s self-assessments and the doctor’s diagnosis of the type of problem should be investigated.

A practical tool for monitoring health has been translated and published to prevent the emergence of different versions and allow for comparison of research findings conducted in various countries. The PFM questionnaire has been translated into Persian using standard methods, and cultural contexts have been considered. Its validity and reliability have been confirmed for use among Persian-speaking people. In future studies, the PFM questionnaire can be administered electronically via mobile apps, saving time and streamlining data collection and processing. Based on the current research results, the physical fitness mapping questionnaire for the lower back region has introduced a new method for accurately recording the types of back pain problems people face. This method is reliable and valid in monitoring and recording the symptoms and functional limitations caused by back pain.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical considerations regarding research and the protection of individuals’ privacy have been strictly adhered to in the conduct of this study for the article.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contribute to preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants who contributed to the study.

References

- Ekman M, Jönhagen S, Hunsche E, Jönsson L. Burden of illness of chronic low back pain in Sweden: A cross-sectional, retrospective study in primary care setting. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30(15):1777-85. [DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000171911.99348.90] [PMID]

- Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Wardlaw D, Russell IT. Developing a valid and reliable measure of health outcome for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1994; 19(17):1887-96. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-199409000-00004] [PMID]

- Björklund M, Hamberg J, Heiden M, Barnekow-Bergkvist M. The assessment of symptoms and functional limitations in low back pain patients: validity and reliability of a new questionnaire. European Spine Journal. 2007; 16(11):1799-811. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-007-0405-z] [PMID]

- Turk DC. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002; 18(6):355-65. [DOI:10.1097/00002508-200211000-00003] [PMID]

- Rainville J, Ahern DK, Phalen L, Childs LA, Sutherland R. The association of pain with physical activities in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992; 17(9):1060-4. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-199209000-00008] [PMID]

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005; 113(1-2):9-19. [PMID]

- Ong KS, Seymour RA. Pain measurement in humans. The Surgeon. 2004; 2(1):15-27. [DOI:10.1016/S1479-666X(04)80133-1] [PMID]

- WHO. International classification of functioning, dis ability and health ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.[Link]

- Grotle M, Brox JI, Vøllestad NK. Functional status and disability questionnaires: What do they assess? A systematic review of back-specific outcome questionnaires. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30(1):130-40. [DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000149184.16509.73] [PMID]

- Müller U, Röder C, Greenough CG. Back related outcome assessment instruments. European Spine Journal. 2006; 15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S25-31. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-005-1054-8] [PMID]

- Waddell G, Main CJ. Assessment of severity in lowback disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984; 9(2):204-8. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-198403000-00012] [PMID]

- Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25(24):3115-24. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006] [PMID]

- Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996; 34(3):220-33. [DOI:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003] [PMID]

- Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Leplège A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998; 51(11):913-23. [DOI:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00082-1] [PMID]

- Khodayarifard M, Khorami Markani A, Ghobari Bonab B, Sohrabi F, Zamanpour E, Raghebian R, et al. [Development and Determination of Content and Face Validity of Spiritual Intelligence Scale in Iranian Students (Persian)]. Journal of Applied Psychological Research. 2017; 7(4):39-49. [DOI:10.22059/japr.2017.61079]

- Romero Jeldres M, Díaz Costa E, Faouzi Nadim T. A review of Lawshe’s method for calculating content validity in the social sciences. Frontiers in Education. 2023; 8: 1271335. [DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1271335]

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Owen, Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007; 30(4):459-67. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199] [PMID]

- Margolis RB, Chibnall JT, Tait RC. Test re-test reliability of the pain drawing instrument. Pain. 1988; 33(1):49-51. [DOI:10.1016/0304-3959(88)90202-3] [PMID]

- Ohnmeiss DD. Repeatability of pain drawings in a low back pain population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25(8):980-8. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200004150-00014] [PMID]

- Mirkarimpour SH, Alizadeh MH, Rajabi R, Kazemnejad A. [Validity and Reliability of the Persian Version of Oslo Sport Trauma Research Center Questionnaire on Health Problems (OSTRC) (Persian)]. Sport Sciences and Health Research. 2018; 10(1):1-17. [DOI:10.22059/jsmed.2019.217948.773]

- Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: Theory and application. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006; 119(2):166.e7-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.036] [PMID]

- Polit DF. Getting serious about test re-test reliability: A critique of retest research and some recommendations. Quality of Life Research. 2014; 23(6):1713-20. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-014-0632-9] [PMID]

- Wallwork SB, Braithwaite FA, O'Keeffe M, Travers MJ, Summers SJ, Lange B, et al. The clinical course of acute, subacute and persistent low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2024; 196(2):E29-46. [DOI:10.1503/cmaj.230542] [PMID]

- Pierobon A, Darlow B. Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (Back-PAQ). In: Krägeloh CU, Alyami M, Medvedev ON, Medvedev ON, editors. International handbook of behavioral health assessment. Cham: Springer; 2023. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-89738-3_12-1]

- O'Hagan ET, Skinner IW, Jones MD, Karran EL, Traeger AC, Cashin AG, et al. Development and measurement properties of the AxEL (attitude toward education and advice for low-back-pain) questionnaire. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2022; 20(1):4. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-021-01908-4] [PMID]

- Jorgensen JE, Rathleff CR, Rathleff MS, Andreasen J. Danish translation and validation of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre questionnaires on overuse injuries and health problems. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2016; 26(12):1391-7. [DOI:10.1111/sms.12590] [PMID]

- Draugalis JR, Coons SJ, Plaza CM. Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2008; 72(1):11. [DOI:10.5688/aj720111] [PMID]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Sport injury and corrective exercises

Received: 2024/04/22 | Accepted: 2024/05/26 | Published: 2024/10/1

Received: 2024/04/22 | Accepted: 2024/05/26 | Published: 2024/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |