Sun, Dec 14, 2025

Volume 10, Issue 3 (Summer 2020)

PTJ 2020, 10(3): 135-144 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ebrahimi Varkiani M, Alizadeh M H, Rajabi R, Minoonejad H. Comparing Two Sports Injury Surveillance Systems: A Novel Systematic Approach. PTJ 2020; 10 (3) :135-144

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-400-en.html

URL: http://ptj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-400-en.html

1- Department of Sports Injuries and Corrective Exercises, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 981 kb]

(1744 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4113 Views)

3. Results

The total number of injuries reported via SISS in soccer, volleyball, taekwondo, and wrestling was 81 incidences. No sports injury was reported in handball. In addition, the incidence rate of injury was calculated and reported according to the model of the International Olympic Committee’s injury surveillance system [19].Most of the injuries were reported in taekwondo in both systems; the number of reports in SISS was much higher (Table 1).

.jpg)

Chi-squared test data indicated a significant difference in injury incidence between the two explored systems (Table 2).

.jpg)

The anatomical location of injury was also of the most important indexes. Besides, athletic trainers reported the highest prevalence of injuries in the finger, knee, thigh, and ankle among 40 separated anatomical regions (Table 3).

.jpg)

Other results reported in SISS included a 52% prevalence of injuries on the left side and the rest on the right side of the body. Other indexes that existed in SISS but not in SIRS included the following ones. Concerning injury chronometry, most cases belonged to soccer, volleyball, taekwondo, and wrestling that occurred in late season. However, there was no injury chronometry data in SIRS. More than half of the injuries occurred in the second half of the competition. In other words, it belonged to the second half of the third and fourth rounds. More than half of the injuries happened in provincial competitions. Moreover, 86% and 91% of injuries in football and taekwondo were new injuries, respectively, and the rest were re-injury incidences.

According to reports, 78% of injuries restricted the athlete’s participation for 1 to 3 days. The prevalence of moderate injuries (absence from training or competition for 8-28 days) was approximately 6% in soccer and taekwondo. Additionally, about 90% of reported injuries were acute cases. One of the strengths of SISS was determining the degree of injuries, such as sprains, strains, dislocation, and even concussion. Besides, 57% of sprains were of grade 1 and 43% were of grade 2. Besides, all reported strains (8 cases) were grade. Moreover, 58.1% and 42% of dislocations were reported in incomplete and complete joints, respectively. The only reported head injury was concussion grade 1. All athletic trainers were qualified by the sports medicine federation of Iran.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the injuries reported to SISS and SIRS in 6 months. Sports injuries of all insured athletes who participated at the amateur, semi-professional, and professional levels in organized competitions were collected. Soccer, volleyball, handball, taekwondo, and wrestling were the sports disciplines selected for the study in Alborz Province.

Implementing comprehensive data collection methods and modifying old methods, in addition to the complete reporting of information and reduction of missing data ensure the maximum data quality [20]. The qualified athletic trainers of the sports medicine federation were responsible for reporting the injury to SISS. This is because they are a vital source of data collection and mostly provide the highest quality of reports [6, 21].

The main reason for implementing two systems in the same sample was to eliminate disturbing variables to provide better control over the comparison of two systems [20]. SISS presented key differences in terms of the data collection process with SIRS. In SISS, athletic trainers reported injuries regardless of the athlete’s request to the injury record form. Numerous mild injuries were missed before in SIRS due to the athlete’s unwillingness to treatment; however, they are reported in SISS, because of the new definition and systematic approach of data collection. In 6 months, 81 sports injuries were reported to SISS and only 19 sports injuries reported to SIRS fell in 5 selected sports disciplines in Alborz Province. The injury rate ratio of 4.3 was calculated for the comparison of SISS to SIRS. There was consistency with the study of Finch et al. (2002); they compared a simple injury surveillance system with a comprehensive one and the rate ratio of 3.8 was calculated for these two systems [20].Each investigation signified that implementing a systematic surveillance system may further increase the injury incidence. In the present study, the incidence rate of 1.39 injuries per 1000 athletes was recorded for 81 injuries in SISS, compared to the incidence rate of 0.32 injuries per 1000 athletes recorded for 19 injuries in SIRS. Chi-squared test results presented a significant difference in incidence rates, as well (P<0.05) (Table 2).

There were not many differences between the number of injuries in volleyball and wrestling; there was even no injury report in handball disciplines in the two studied systems. The lack of a club’s support of injury surveillance and athletes’ unwillingness to report an injury may be the cause of limited reports of injury in these disciplines [11]. In addition, the lack of funding and financial support, especially for athletic trainers, as well as medical staff shortage, could be barriers to recording sports injuries [20, 22]. However, in the present study, athletic trainers received no extra fees for recording and reporting injuries in SISS.

The incidence rate of 0.25 injuries per 1000 athletes was recorded for soccer injuries in SIRS; however, the same rate was approximately 0.59 injuries per 1000 athletes in SISS. Concerning taekwondo, SIRS reported a rate of 0.51 injuries per 1000 athletes; however, SISS reported a rate of 4 injuries per 1000 athletes over 6 months. The present research results indicated a significant difference between the injuries reported in the two methods of collecting and recording sports injuries. The difference in the definition of injury in SIRS and SISS could probably explain the lower injury rate. At least one-day absence from practice or competition was included in the definition of injury in SIRS; however, injuries in SISS were collected regardless of the absence of the player from practice or competition due to the injury [3]. Therefore, the loss of numerous mild injuries was prevented. These results were consistent with those of Dampier et al. (2015). Limiting the definition of injuries to the player’s absence from practice or competition is a major limitation in the epidemiology of injuries. Accordingly, the prevalence rate of sports injuries when the definition of injury is not limited to the player’s absence from practice or competition is higher than that of including at least one-day absence [23].Therefore, athletic trainers had to record injuries according to the definition of injury in SISS. As a result, 30 cases of bruising were reported in the system, which included >35% of the total injuries. The data about mild injuries may seem less important; however, it could be effective in making vital decisions. Anderson et al. (2004) found that 20% of head injuries in football were in part due to the player’s elbow hitting the opponent’s head as a result of heading dual in the competition. Therefore, passing laws that limit the players using their hands and elbows in heading duels could reduce the risk of head injuries [4, 24]. In the structure of SISS, multiples defects of SIRS are addressed which could lead to missing injury data, such as the athlete’s failure to visit the board, missing low-intensity sports injuries, the athlete’s unwillingness to report the injury, and the lack of the athlete’s need to receive medical treatment services. Athletes’ use of other health insurances, non-reporting of mild injuries by an athletic trainer, the dependence of the injury report on the athlete’s presenting of the injury record form to the medical board, and the limited importance of the injury for the athlete were other reasons of missing data [25]. In addition, the incidence rate ratio in volleyball and wrestling was not as expected; thus, the researcher assumes that athletic trainers in volleyball and wrestling competitions were not well controlled.

Employing practical and user-friendly tools is essential in the proper reporting of injuries [26]. Therefore, a user-friendly and easy-access smartphone-based application was designed in SISS. An injury report was possible anywhere even near the court as soon as possible. Reporting the injury was possible later at home as well. Those athletic trainers without smartphones could report injuries via the web-based form through their private account in SISS. However, this was not an option in SIRS.

There was no index of injury type in SIRS. For this reason, only this index result was only presented for SISS. All injury types were provided in SISS to be selected by athletic trainers. Subsequently, bruising (37%), dislocation (13.3%), sprint (9.8%), and strain (8.6%) were orderly the most frequent injuries in SISS. The highest number of bruises was reported in taekwondo (41%) and soccer (28.5%). Knee and ankle were the most prevalent anatomical regions in both investigated systems. Knee (36.8%) and ankle (15.7%) were the most common body regions injured in SIRS (Table 4).

.jpg)

However, fingers (18.5%), knee (17.2%), thigh (14.8%), and ankle (11.1%) shaped the highest prevalence of injuries in SISS (Table 5).

.jpg)

In total, 7 cases of finger injuries were mild bruising. The possibility of SISS to comprehensively record the mild injuries and reduce data missing has made it to identify the most common injures more accurately. As per the system output, 26 out of 30 bruises were mild. Furthermore, in a comparison of SIRS to SISS, different frequencies of injuries, like 3 versus 9 ankle injuries and 1 versus 15 finger injuries were presented in the two systems. The Chi-squared test data also supported the difference in the prevalence of injuries in the most common anatomical locations in the two systems (P<0.05) (Table 6).

.jpg)

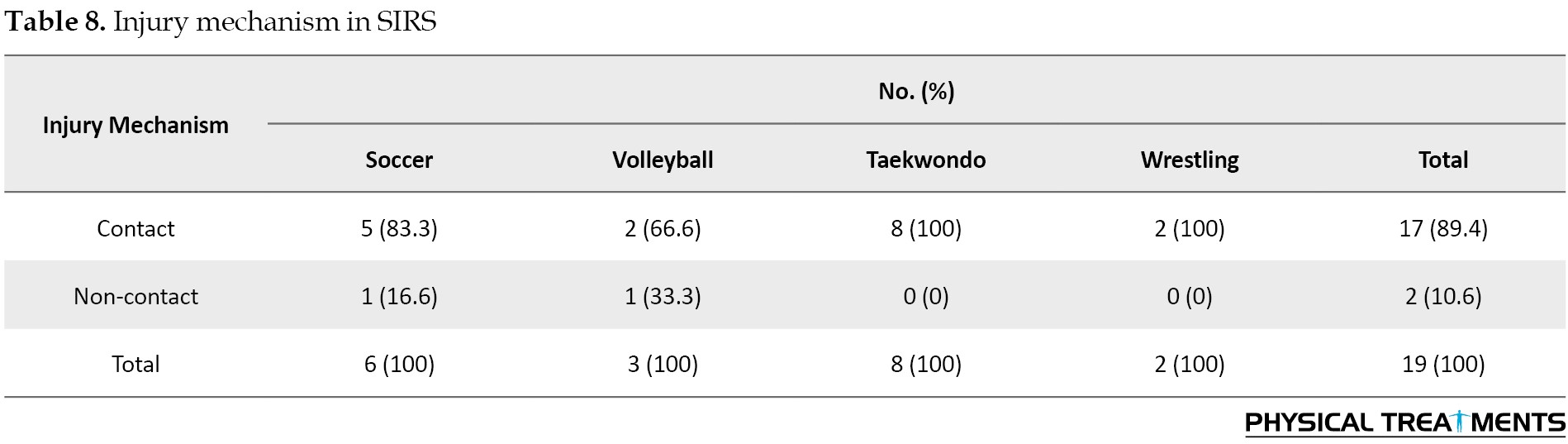

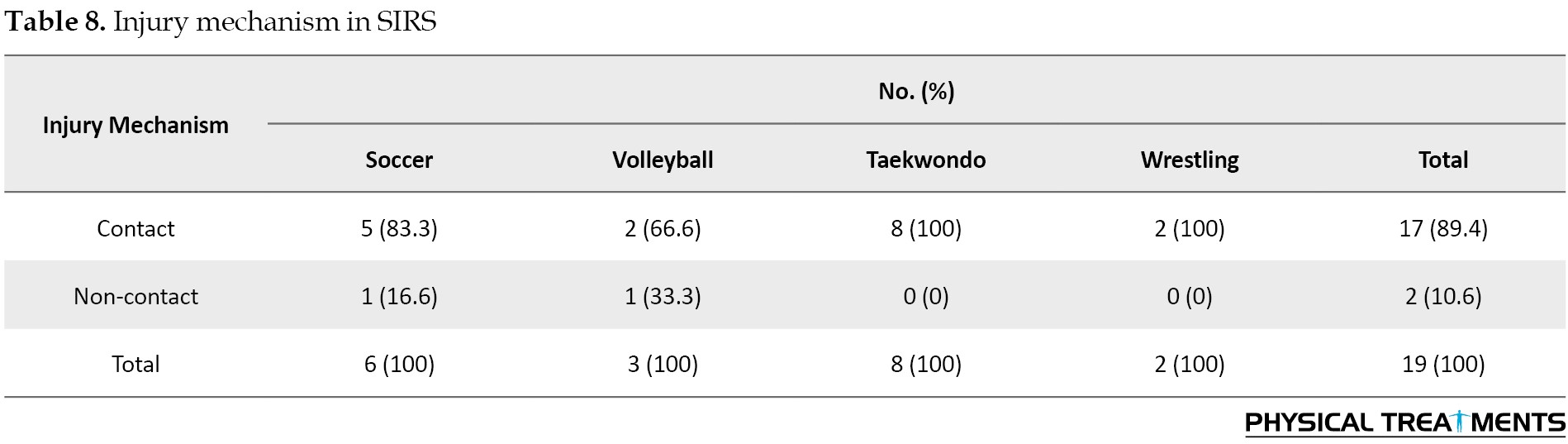

SIRS divided the mechanism of injury into two options of contact and non-contact, which provide a limited choice for athletic trainers. However, SISS addressed more options of injury mechanisms. Additionally, concerning the type of movement leading to injury on the field, dynamic options were designed in the application; thus, athletic trainers could easily find and select the desired option in each sport, such as tackling or shooting in soccer, or landing in volleyball. Accordingly, >90% of injury mechanisms were contact in both systems. SISS reported >70% of injuries as contact with players or competitors. Contact with playing surface (8.6%) was ranked the second. In the case of the movement type leading to injury, 21% of soccer injuries were caused by tackling and being tackled. In taekwondo, the most prevalent injuries were due to a kick (38%) and receiving a kick (34%) (Table 7 & 8).

Creating more options in the mechanism of injury and movement leading to injury enabled athletic trainers to more accurately record and report the injury mechanism. Studies reported that providing specific codes of command could facilitate injury surveillance [26]. Accordingly, compared to SIRS, SISS could provide accurate and comprehensive indicators to report information related to sports injuries. Furthermore, 51.5% and 48.1% of injuries occurred on the left and right sides, respectively. There exist many other indexes in SISS, i.e. not considered in SIRS. Some examples of these indexes include injury chronometry, level of the competition/practice, injury severity, injury nature, the degree of concussion, sprain, strain, and joint dislocation.

5. Conclusion

Recording sports injuries with a systematic and web-based approach via an application and paperless indicated that if comprehensive electronic surveillance methods are used for data collection, the possibility of not reporting injuries may be reduced. Less injury data is likely to be lost as well. It is also effective to employ easy access and user-friendly tools to record sports injuries. Therefore, it is recommended to replace the smartphone-based applications with paper-based forms via a systematic surveillance approach to facilitate and accelerate injury reporting and reduce missing data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Sports Medicine Federation of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Sports Medicine Board of Alborz Province for their cooperation and support of the present study.

References

Full-Text: (1934 Views)

1. Introduction

he active participation of all individuals in exercises should be on the agenda of every society to benefit from active life and sports. Furthermore, enhanced participation in sports could also increase the prevalence of sports injuries [1, 2]. The increase of injuries is an essential issue in public health; its socio-economic costs have become an important challenge for countries [1]. Injuries impose huge direct and indirect costs to athletes, clubs, and insurance companies; prevent athletes from attending training and matches for days and even months, and lead to the loss of job opportunities and decreased quality of life [3]. To maintain the population participating in sports, it is necessary to identify injuries and reduce those by preventive strategies [4, 5]. For this reason, numerous countries use injury surveillance systems to reach successful prevention [6]. Accordingly, information about injuries is systematically collected to identify the risk factors and the process of long-term damage [7]. The design and evaluation of these strategies depend on continuous access to high-quality longitudinal data on sports injuries. However, continuous and systematic collection of sports injury information is rarely achieved [8]. Sports injury data collection is the first step in achieving injury prevention [9]. Recent strategies have reported injury surveillance as the first and most significant step in injury prevention [10]. Sports injury surveillance systems attempt to collect information related to sports injuries by organizing data from individuals, such as a physician, athletic trainers, and so on. There are comprehensive data on sports injuries at the provincial and national levels reported over several years [3, 11, 12, 13]. Continuous data collection is among the strengths of such systems [14].

In Iran, sports injury data collection is performed by sports medicine boards through the Sports Injury Recording System (SIRS) of the sports medicine federation. Ebrahimi et al. (2012) reported the deficiencies of this system. The lack of indexes, such as the type, severity, and time of injury, re-injury, and other information related to sports injuries that could significantly affect the next step of the prevention process. Additionally, this system fails to report the incidence rate of injury and classified reports [3]. The difference between the two systems of sports injury recording and sports injury surveillance could be better understood by the definition in which injury surveillance refers to the ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of health information [7]. However, injury collection in injury recording systems is conducted regardless of systematic, analytical, and interpretive operations.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a systematic review of injury surveillance could improve and expand the minimum dataset to at least include a significant narrative text; it also enables us to potentially expand the necessary mechanism codes [14]. This is a defect in numerous injury surveillance systems. Besides, the WHO recommends addressing these deficiencies. An incomplete and unorganized implementation may affect the collected data. Studies indicated that correct and convenient structure in performance and operation are the key indicators of a successful surveillance system [15]. Presenting the paper-based injury report form by the athlete to the provincial board of sports medicine federation was a defect in implementation. Moreover, missing data due to having no injury definition in the sports injury recording system was another weakness in this area. However, in professional injury surveillance systems, athletic trainers/physicians report injuries directly to the system via web-based injury record forms, weekly. The web-based injury reports are developing; accordingly, in the Paralympic Games in London, all injuries were recorded using the medical staff of each country through the web-based surveillance system [16]. Studies have also provided more accurate and realistic reports on employing online tools, compared to the paper-based systems [8, 17]. National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system changed its method to online data collection for improving its efficiency and cost-effectiveness [18].

There is a lack of a comprehensive sports injury surveillance system, as well as online, convenient, and accessible tools in this regard. There are also defects in organized and systematic implementation in this area. Therefore, the present study aimed to design and implement a comprehensive Sports Injury Surveillance System (SISS) and compare the result with the Sports Injury Recording System (SIRS) output.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive and retrospective study in terms of practical purpose and data collection. The statistical population of the present study included 58265 athletes covered by the sports insurance of sports medicine federation in Alborz Province, Iran. Data collection of sports injuries was performed in football (n=23449), volleyball (n=13640), handball (n=384), taekwondo (n=15511), and wrestling (n=5231) athletes by a systematic approach of surveillance. The statistical sample also included athletes whose injuries were recorded in competitions by an athletic trainer of the Sports Medicine Federation in SISS. A smartphone-based application was created to record sports injuries into SISS. A web-based injury record form was also provided for those athletic trainers without smartphones.

The sports injuries that occurred in the competitions organized in the 5 mentioned discipline in Alborz Province, Iran were recorded by the athletic trainers according to the definition in both genders in 6 months (from 22/12/2017 to 21/06/2018). Due to limited access to clubs and the absence of athletic trainers in sports clubs, recording sports injuries during practice was impossible. To compare the results, sports injuries reporting to the SIRS was conducted according to their previous usual method alongside the process of reporting injuries to the federation’s SISS in the same population. According to the previous procedure of reporting injuries, the paper-based injury report form was completed by the athletic trainers. It was then provided to the athlete to follow up on the treatment process. Due to the legal requirements of athletes to follow up on the treatment process and reimbursing treatment costs from the federation, the Alborz Sports Medicine Board of Alborz Province emphasized reporting sports injuries to SIRS according to the previous routine. The implementation process in SIRS was as follows: the injury record form was completed by the athletic trainer according to the need of the injured athlete’s follow-up and treatment. The information provided in the form includes age, gender, the date of injury, body part, as well as the contact and non-contact mechanism of injury. The injured athlete refers to the board for treatment costs reimbursement by presenting the completed injury record form and hospital treatment documents. Then, the data form was recorded in the SIRS by provincial board staff.

SIRS’s injury record form included information on the athlete’s personal information, sports type, province and city, practice/competition, competition level, injury mechanism, and the injured body part. The SISS’s injury record form also included numerous essential epidemiological indexes. Indexes, such as injury type, anatomical location, injury chronometry, injury time lost, injury onset, clinical outcome, environmental location, injury mechanism, and so on. Workshop sessions were held for the athletic trainers of Alborz Province to justify them about the injury definition and application use. In the workshops, it was emphasized to report the injuries according to the provided definition. In the present study, a reportable injury in SISS was defined as any complaint that occurred as a result of participation in organized practice or competition and required medical attention regardless of absence from practice or competition.

A personal account was created in SISS for each athletic trainer. More than 60% of the athletic trainers of Alborz Province collaborated with the present study. To facilitate the process of recording and reporting injuries into SISS, the software and application were designed based on smartphones; it was provided to athletic trainers to record injury information at any time. According to the report of athletic trainers participated in this study, despite a large number of questions in the application, it has provided convenience and rapid information registration. Athletic trainers’ access to SISS was possible through two methods; a web-based form via an independent link (http://siss.ifsm.ir:8080/injury/), and a smartphone-based application on the android operating system (Figure 1).

he active participation of all individuals in exercises should be on the agenda of every society to benefit from active life and sports. Furthermore, enhanced participation in sports could also increase the prevalence of sports injuries [1, 2]. The increase of injuries is an essential issue in public health; its socio-economic costs have become an important challenge for countries [1]. Injuries impose huge direct and indirect costs to athletes, clubs, and insurance companies; prevent athletes from attending training and matches for days and even months, and lead to the loss of job opportunities and decreased quality of life [3]. To maintain the population participating in sports, it is necessary to identify injuries and reduce those by preventive strategies [4, 5]. For this reason, numerous countries use injury surveillance systems to reach successful prevention [6]. Accordingly, information about injuries is systematically collected to identify the risk factors and the process of long-term damage [7]. The design and evaluation of these strategies depend on continuous access to high-quality longitudinal data on sports injuries. However, continuous and systematic collection of sports injury information is rarely achieved [8]. Sports injury data collection is the first step in achieving injury prevention [9]. Recent strategies have reported injury surveillance as the first and most significant step in injury prevention [10]. Sports injury surveillance systems attempt to collect information related to sports injuries by organizing data from individuals, such as a physician, athletic trainers, and so on. There are comprehensive data on sports injuries at the provincial and national levels reported over several years [3, 11, 12, 13]. Continuous data collection is among the strengths of such systems [14].

In Iran, sports injury data collection is performed by sports medicine boards through the Sports Injury Recording System (SIRS) of the sports medicine federation. Ebrahimi et al. (2012) reported the deficiencies of this system. The lack of indexes, such as the type, severity, and time of injury, re-injury, and other information related to sports injuries that could significantly affect the next step of the prevention process. Additionally, this system fails to report the incidence rate of injury and classified reports [3]. The difference between the two systems of sports injury recording and sports injury surveillance could be better understood by the definition in which injury surveillance refers to the ongoing and systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of health information [7]. However, injury collection in injury recording systems is conducted regardless of systematic, analytical, and interpretive operations.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a systematic review of injury surveillance could improve and expand the minimum dataset to at least include a significant narrative text; it also enables us to potentially expand the necessary mechanism codes [14]. This is a defect in numerous injury surveillance systems. Besides, the WHO recommends addressing these deficiencies. An incomplete and unorganized implementation may affect the collected data. Studies indicated that correct and convenient structure in performance and operation are the key indicators of a successful surveillance system [15]. Presenting the paper-based injury report form by the athlete to the provincial board of sports medicine federation was a defect in implementation. Moreover, missing data due to having no injury definition in the sports injury recording system was another weakness in this area. However, in professional injury surveillance systems, athletic trainers/physicians report injuries directly to the system via web-based injury record forms, weekly. The web-based injury reports are developing; accordingly, in the Paralympic Games in London, all injuries were recorded using the medical staff of each country through the web-based surveillance system [16]. Studies have also provided more accurate and realistic reports on employing online tools, compared to the paper-based systems [8, 17]. National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system changed its method to online data collection for improving its efficiency and cost-effectiveness [18].

There is a lack of a comprehensive sports injury surveillance system, as well as online, convenient, and accessible tools in this regard. There are also defects in organized and systematic implementation in this area. Therefore, the present study aimed to design and implement a comprehensive Sports Injury Surveillance System (SISS) and compare the result with the Sports Injury Recording System (SIRS) output.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive and retrospective study in terms of practical purpose and data collection. The statistical population of the present study included 58265 athletes covered by the sports insurance of sports medicine federation in Alborz Province, Iran. Data collection of sports injuries was performed in football (n=23449), volleyball (n=13640), handball (n=384), taekwondo (n=15511), and wrestling (n=5231) athletes by a systematic approach of surveillance. The statistical sample also included athletes whose injuries were recorded in competitions by an athletic trainer of the Sports Medicine Federation in SISS. A smartphone-based application was created to record sports injuries into SISS. A web-based injury record form was also provided for those athletic trainers without smartphones.

The sports injuries that occurred in the competitions organized in the 5 mentioned discipline in Alborz Province, Iran were recorded by the athletic trainers according to the definition in both genders in 6 months (from 22/12/2017 to 21/06/2018). Due to limited access to clubs and the absence of athletic trainers in sports clubs, recording sports injuries during practice was impossible. To compare the results, sports injuries reporting to the SIRS was conducted according to their previous usual method alongside the process of reporting injuries to the federation’s SISS in the same population. According to the previous procedure of reporting injuries, the paper-based injury report form was completed by the athletic trainers. It was then provided to the athlete to follow up on the treatment process. Due to the legal requirements of athletes to follow up on the treatment process and reimbursing treatment costs from the federation, the Alborz Sports Medicine Board of Alborz Province emphasized reporting sports injuries to SIRS according to the previous routine. The implementation process in SIRS was as follows: the injury record form was completed by the athletic trainer according to the need of the injured athlete’s follow-up and treatment. The information provided in the form includes age, gender, the date of injury, body part, as well as the contact and non-contact mechanism of injury. The injured athlete refers to the board for treatment costs reimbursement by presenting the completed injury record form and hospital treatment documents. Then, the data form was recorded in the SIRS by provincial board staff.

SIRS’s injury record form included information on the athlete’s personal information, sports type, province and city, practice/competition, competition level, injury mechanism, and the injured body part. The SISS’s injury record form also included numerous essential epidemiological indexes. Indexes, such as injury type, anatomical location, injury chronometry, injury time lost, injury onset, clinical outcome, environmental location, injury mechanism, and so on. Workshop sessions were held for the athletic trainers of Alborz Province to justify them about the injury definition and application use. In the workshops, it was emphasized to report the injuries according to the provided definition. In the present study, a reportable injury in SISS was defined as any complaint that occurred as a result of participation in organized practice or competition and required medical attention regardless of absence from practice or competition.

A personal account was created in SISS for each athletic trainer. More than 60% of the athletic trainers of Alborz Province collaborated with the present study. To facilitate the process of recording and reporting injuries into SISS, the software and application were designed based on smartphones; it was provided to athletic trainers to record injury information at any time. According to the report of athletic trainers participated in this study, despite a large number of questions in the application, it has provided convenience and rapid information registration. Athletic trainers’ access to SISS was possible through two methods; a web-based form via an independent link (http://siss.ifsm.ir:8080/injury/), and a smartphone-based application on the android operating system (Figure 1).

3. Results

The total number of injuries reported via SISS in soccer, volleyball, taekwondo, and wrestling was 81 incidences. No sports injury was reported in handball. In addition, the incidence rate of injury was calculated and reported according to the model of the International Olympic Committee’s injury surveillance system [19].Most of the injuries were reported in taekwondo in both systems; the number of reports in SISS was much higher (Table 1).

.jpg)

Chi-squared test data indicated a significant difference in injury incidence between the two explored systems (Table 2).

.jpg)

The anatomical location of injury was also of the most important indexes. Besides, athletic trainers reported the highest prevalence of injuries in the finger, knee, thigh, and ankle among 40 separated anatomical regions (Table 3).

.jpg)

Other results reported in SISS included a 52% prevalence of injuries on the left side and the rest on the right side of the body. Other indexes that existed in SISS but not in SIRS included the following ones. Concerning injury chronometry, most cases belonged to soccer, volleyball, taekwondo, and wrestling that occurred in late season. However, there was no injury chronometry data in SIRS. More than half of the injuries occurred in the second half of the competition. In other words, it belonged to the second half of the third and fourth rounds. More than half of the injuries happened in provincial competitions. Moreover, 86% and 91% of injuries in football and taekwondo were new injuries, respectively, and the rest were re-injury incidences.

According to reports, 78% of injuries restricted the athlete’s participation for 1 to 3 days. The prevalence of moderate injuries (absence from training or competition for 8-28 days) was approximately 6% in soccer and taekwondo. Additionally, about 90% of reported injuries were acute cases. One of the strengths of SISS was determining the degree of injuries, such as sprains, strains, dislocation, and even concussion. Besides, 57% of sprains were of grade 1 and 43% were of grade 2. Besides, all reported strains (8 cases) were grade. Moreover, 58.1% and 42% of dislocations were reported in incomplete and complete joints, respectively. The only reported head injury was concussion grade 1. All athletic trainers were qualified by the sports medicine federation of Iran.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the injuries reported to SISS and SIRS in 6 months. Sports injuries of all insured athletes who participated at the amateur, semi-professional, and professional levels in organized competitions were collected. Soccer, volleyball, handball, taekwondo, and wrestling were the sports disciplines selected for the study in Alborz Province.

Implementing comprehensive data collection methods and modifying old methods, in addition to the complete reporting of information and reduction of missing data ensure the maximum data quality [20]. The qualified athletic trainers of the sports medicine federation were responsible for reporting the injury to SISS. This is because they are a vital source of data collection and mostly provide the highest quality of reports [6, 21].

The main reason for implementing two systems in the same sample was to eliminate disturbing variables to provide better control over the comparison of two systems [20]. SISS presented key differences in terms of the data collection process with SIRS. In SISS, athletic trainers reported injuries regardless of the athlete’s request to the injury record form. Numerous mild injuries were missed before in SIRS due to the athlete’s unwillingness to treatment; however, they are reported in SISS, because of the new definition and systematic approach of data collection. In 6 months, 81 sports injuries were reported to SISS and only 19 sports injuries reported to SIRS fell in 5 selected sports disciplines in Alborz Province. The injury rate ratio of 4.3 was calculated for the comparison of SISS to SIRS. There was consistency with the study of Finch et al. (2002); they compared a simple injury surveillance system with a comprehensive one and the rate ratio of 3.8 was calculated for these two systems [20].Each investigation signified that implementing a systematic surveillance system may further increase the injury incidence. In the present study, the incidence rate of 1.39 injuries per 1000 athletes was recorded for 81 injuries in SISS, compared to the incidence rate of 0.32 injuries per 1000 athletes recorded for 19 injuries in SIRS. Chi-squared test results presented a significant difference in incidence rates, as well (P<0.05) (Table 2).

There were not many differences between the number of injuries in volleyball and wrestling; there was even no injury report in handball disciplines in the two studied systems. The lack of a club’s support of injury surveillance and athletes’ unwillingness to report an injury may be the cause of limited reports of injury in these disciplines [11]. In addition, the lack of funding and financial support, especially for athletic trainers, as well as medical staff shortage, could be barriers to recording sports injuries [20, 22]. However, in the present study, athletic trainers received no extra fees for recording and reporting injuries in SISS.

The incidence rate of 0.25 injuries per 1000 athletes was recorded for soccer injuries in SIRS; however, the same rate was approximately 0.59 injuries per 1000 athletes in SISS. Concerning taekwondo, SIRS reported a rate of 0.51 injuries per 1000 athletes; however, SISS reported a rate of 4 injuries per 1000 athletes over 6 months. The present research results indicated a significant difference between the injuries reported in the two methods of collecting and recording sports injuries. The difference in the definition of injury in SIRS and SISS could probably explain the lower injury rate. At least one-day absence from practice or competition was included in the definition of injury in SIRS; however, injuries in SISS were collected regardless of the absence of the player from practice or competition due to the injury [3]. Therefore, the loss of numerous mild injuries was prevented. These results were consistent with those of Dampier et al. (2015). Limiting the definition of injuries to the player’s absence from practice or competition is a major limitation in the epidemiology of injuries. Accordingly, the prevalence rate of sports injuries when the definition of injury is not limited to the player’s absence from practice or competition is higher than that of including at least one-day absence [23].Therefore, athletic trainers had to record injuries according to the definition of injury in SISS. As a result, 30 cases of bruising were reported in the system, which included >35% of the total injuries. The data about mild injuries may seem less important; however, it could be effective in making vital decisions. Anderson et al. (2004) found that 20% of head injuries in football were in part due to the player’s elbow hitting the opponent’s head as a result of heading dual in the competition. Therefore, passing laws that limit the players using their hands and elbows in heading duels could reduce the risk of head injuries [4, 24]. In the structure of SISS, multiples defects of SIRS are addressed which could lead to missing injury data, such as the athlete’s failure to visit the board, missing low-intensity sports injuries, the athlete’s unwillingness to report the injury, and the lack of the athlete’s need to receive medical treatment services. Athletes’ use of other health insurances, non-reporting of mild injuries by an athletic trainer, the dependence of the injury report on the athlete’s presenting of the injury record form to the medical board, and the limited importance of the injury for the athlete were other reasons of missing data [25]. In addition, the incidence rate ratio in volleyball and wrestling was not as expected; thus, the researcher assumes that athletic trainers in volleyball and wrestling competitions were not well controlled.

Employing practical and user-friendly tools is essential in the proper reporting of injuries [26]. Therefore, a user-friendly and easy-access smartphone-based application was designed in SISS. An injury report was possible anywhere even near the court as soon as possible. Reporting the injury was possible later at home as well. Those athletic trainers without smartphones could report injuries via the web-based form through their private account in SISS. However, this was not an option in SIRS.

There was no index of injury type in SIRS. For this reason, only this index result was only presented for SISS. All injury types were provided in SISS to be selected by athletic trainers. Subsequently, bruising (37%), dislocation (13.3%), sprint (9.8%), and strain (8.6%) were orderly the most frequent injuries in SISS. The highest number of bruises was reported in taekwondo (41%) and soccer (28.5%). Knee and ankle were the most prevalent anatomical regions in both investigated systems. Knee (36.8%) and ankle (15.7%) were the most common body regions injured in SIRS (Table 4).

.jpg)

However, fingers (18.5%), knee (17.2%), thigh (14.8%), and ankle (11.1%) shaped the highest prevalence of injuries in SISS (Table 5).

.jpg)

In total, 7 cases of finger injuries were mild bruising. The possibility of SISS to comprehensively record the mild injuries and reduce data missing has made it to identify the most common injures more accurately. As per the system output, 26 out of 30 bruises were mild. Furthermore, in a comparison of SIRS to SISS, different frequencies of injuries, like 3 versus 9 ankle injuries and 1 versus 15 finger injuries were presented in the two systems. The Chi-squared test data also supported the difference in the prevalence of injuries in the most common anatomical locations in the two systems (P<0.05) (Table 6).

.jpg)

SIRS divided the mechanism of injury into two options of contact and non-contact, which provide a limited choice for athletic trainers. However, SISS addressed more options of injury mechanisms. Additionally, concerning the type of movement leading to injury on the field, dynamic options were designed in the application; thus, athletic trainers could easily find and select the desired option in each sport, such as tackling or shooting in soccer, or landing in volleyball. Accordingly, >90% of injury mechanisms were contact in both systems. SISS reported >70% of injuries as contact with players or competitors. Contact with playing surface (8.6%) was ranked the second. In the case of the movement type leading to injury, 21% of soccer injuries were caused by tackling and being tackled. In taekwondo, the most prevalent injuries were due to a kick (38%) and receiving a kick (34%) (Table 7 & 8).

Creating more options in the mechanism of injury and movement leading to injury enabled athletic trainers to more accurately record and report the injury mechanism. Studies reported that providing specific codes of command could facilitate injury surveillance [26]. Accordingly, compared to SIRS, SISS could provide accurate and comprehensive indicators to report information related to sports injuries. Furthermore, 51.5% and 48.1% of injuries occurred on the left and right sides, respectively. There exist many other indexes in SISS, i.e. not considered in SIRS. Some examples of these indexes include injury chronometry, level of the competition/practice, injury severity, injury nature, the degree of concussion, sprain, strain, and joint dislocation.

5. Conclusion

Recording sports injuries with a systematic and web-based approach via an application and paperless indicated that if comprehensive electronic surveillance methods are used for data collection, the possibility of not reporting injuries may be reduced. Less injury data is likely to be lost as well. It is also effective to employ easy access and user-friendly tools to record sports injuries. Therefore, it is recommended to replace the smartphone-based applications with paper-based forms via a systematic surveillance approach to facilitate and accelerate injury reporting and reduce missing data.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles are considered in this article. The participants were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing all parts of the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Sports Medicine Federation of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Sports Medicine Board of Alborz Province for their cooperation and support of the present study.

References

- Macedo P, Madeira RN, Correia A, Jardim M. A Web System based on a Sports injuries model towards global athletes monitoring. In: Rocha Á, Correia AM, Tan FB, Stroetmann KA, editors. New perspectives in information systems and technologies. Cham: Springer Science & Business Media; 2014. pp. 377-83. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-05948-8_36]

- Nicholl JP, Coleman P, Williams BT. The epidemiology of sports and exercise related injury in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 1995; 29(4):232-8. [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.29.4.232] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ebrahimi Varkiani M, Alizadeh MH, pourkazemi. L. Epidemiology of sport injuries of Iran’s athletes via IRI sport medicine federation database: 21 sports in 2009-2011. [MA. thesis] Tehran: University of Tehran; 2013.

- Bahr R, Engebretsen L. Sports injury prevention. Chichester: Blackwell Pub; 2009. [DOI:10.1002/9781444303612]

- Belechri M, Petridou E, Kedikoglou S, Trichopoulos D. Sports injuries among children in six European :union: countries. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2001; 17(11):1005-12. [DOI:10.1023/A:1020078522493] [PMID]

- Kerr ZY, Comstock RD, Dompier TP, Marshall SW. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance (2004-2005 through 2013-2014): Methods of the national collegiate athletic association injury surveillance program and high school reporting information online. Journal of Athletic Training. 2018; 53(8):729-37. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-143-17] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Holder Y, Organization WH. Injury surveillance guidelines [Internet]. 2001. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42451

- Ekegren CL, Gabbe BJ, Finch CF. Sports injury surveillance systems: A review of methods and data quality. Sports Medicine. 2016; 46(1):49-65. [DOI:10.1007/s40279-015-0410-z] [PMID]

- van Mechelen W. Sports injury surveillance systems. ‘One size fits all’? Sports Medicine. 1997; 24(3):164-8. [DOI:10.2165/00007256-199724030-00003] [PMID]

- Finch CF, Donaldson A. A sports setting matrix for understanding the implementation context for community sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010; 44(13):973-8. [DOI:10.1136/bjsm.2008.056069] [PMID]

- Ekegren CL, Donaldson A, Gabbe BJ, Finch CF. Implementing injury surveillance systems alongside injury prevention programs: evaluation of an online surveillance system in a community setting. Injury Epidemiology. 2014; 1(1):19. [DOI:10.1186/s40621-014-0019-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Cassell E, Kerr E, Clapperton A. Adult sports injury hospitalisations in 16 sports: The football codes, other team ball sports, team bat and stick sports and racquet sports [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4d49/81b7920760ac744cbc8e9494befdd7608266.pdf

- Elias SR. 10-year trend in USA Cup soccer injuries: 1988-1997. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001; 33(3):359-67. [DOI:10.1097/00005768-200103000-00004] [PMID]

- Kipsaina C, Ozanne-Smith J, Routley V. The WHO injury surveillance guidelines: A systematic review of the non-fatal guidelines’ utilization, efficacy and effectiveness. Public Health. 2015; 129(10):1406-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.007] [PMID]

- Edouard P, Branco P, Alonso JM, Junge A. Methodological quality of the injury surveillance system used in international athletics championships. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2016; 19(12):984-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsams.2016.03.012] [PMID]

- Derman W, Schwellnus M, Jordaan E, Blauwet CA, Emery C, Pit-Grosheide P, et al. Illness and injury in athletes during the competition period at the London 2012 Paralympic Games: Development and implementation of a web-based surveillance system (WEB-IISS) for team medical staff. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013; 47(7):420-5. [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092375] [PMID]

- Booher MA, Wisniewski J, Smith BW, Sigurdsson A. Comparison of reporting systems to determine concussion incidence in NCAA Division I collegiate football. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2003; 13(2):93-5. [DOI:10.1097/00042752-200303000-00005] [PMID]

- Dick RW. NCAA injury surveillance system: A tool for health and safety risk management. Athletic Therapy Today. 2006; 11(1):42-4. [DOI:10.1123/att.11.1.42]

- Junge A, Engebretsen L, Mountjoy ML, Alonso JM, Renström PAFH, Aubry MJ, et al. Sports injuries during the summer Olympic games 2008. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009; 37(11):2165-72. [DOI:10.1177/0363546509339357] [PMID]

- Finch CF, Mitchell DJ. A comparison of two injury surveillance systems within sports medicine clinics. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2002; 5(4):321-35. [DOI:10.1016/S1440-2440(02)80020-2]

- Yard EE, Collins CL, Comstock RD. A comparison of high school sports injury surveillance data reporting by certified athletic trainers and coaches. Journal of Athletic Training. 2009; 44(6):645-52. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-44.6.645] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Stadlander MC, Kievit J. Adverse outcomes in surgical patients: Implementation of a nationwide reporting system. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2006; 15(5):320-4. [DOI:10.1136/qshc.2005.016220] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dompier TP, Marshall SW, Kerr ZY, Hayden R. The National Athletic Treatment, Injury And Outcomes Network (Nation): Methods of the surveillance program, 2011-2012 through 2013-2014. Journal of Athletic Training. 2015; 50(8):862-9. [DOI:10.4085/1062-6050-50.5.04] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Andersen TE, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Rule violations as a cause of injuries in male norwegian professional football: Are the referees doing their job? The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2004; 32(1 Suppl):62S-8S. [DOI:10.1177/0363546503261412] [PMID]

- Ekegren C, Donaldson A, Gabbe B, Lloyd D, Cook J, Finch C. The facilitators and barriers to implementing injury surveillance systems alongside injury prevention programs. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2014; 18:e138-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsams.2014.11.134]

- Finch CF, Staines C. Guidance for sports injury surveillance: The 20-year influence of the Australian Sports Injury Data Dictionary. Injury Prevention. 2018; 24(5):372-80. [DOI:10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042580] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2019/06/16 | Accepted: 2020/05/28 | Published: 2020/07/1

Received: 2019/06/16 | Accepted: 2020/05/28 | Published: 2020/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)